Different Century, Same Result.

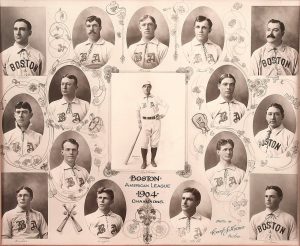

In his book Boston’s 100 Greatest Games, author Rob Sneddon ranked the Red Sox’ come-from-behind win over the Yankees on October 10, 1904, which clinched the American League pennant, No. 86. (Note: Although the Boston and New York teams weren’t called the Red Sox and Yankees until later, Sneddon used the modern names retroactively for simplicity’s sake. As he noted when writing about the 1904 Red Sox in the book’s introduction, “It’s just too awkward to call them the Americans or the Pilgrims or the Puritans or the Plymouth Rocks or the Somersets or any of the other wacky-ass names that the newspapers hung on them at the time.”) What follows is an excerpt from the book, which is available through Amazon and other outlets.

By: Rob Sneddon

There was no American League Championship Series in 1904. Not officially, anyway. But thanks to some scheduling quirks and what the Globe called “the greatest race since baseball was invented,” the Red Sox and Yankees settled the American League pennant with a five-game showdown that prefigured the modern postseason.

In some ways the baseball schedule was more manageable in 1904. There were just eight teams in the American League—none west of St. Louis. Teams played only 154 games. The schedule was perfectly equitable; each team played the others 22 times—eleven at home, eleven on the road.

But in other ways the schedule was a nightmare. There were no night games. Just two AL cities (St. Louis and Chicago) permitted Sunday baseball. Teams traveled by train. Any game that ended in a tie because of darkness or weather was replayed from scratch. Finally, there was no All-Star break. As a result, teams were dragging by September—and because of all the postponements that had accrued by then, September was the most grueling month of all.

In September 1904, for instance, the Red Sox played eleven doubleheaders, including four in as many days against the same team (the Washington Senators). Which makes it even more remarkable that the Red Sox and Yankees (who played ten September doubleheaders) stayed even down the stretch. From August 22 until the final weekend, no more than a game and a half separated Boston and New York atop the American League standings.

A mid-September series before SRO crowds at Boston’s Huntington Avenue Grounds illustrated how extraordinarily taut (and fraught) the race was. The Sox led by half a game when the Yankees came to town for what was originally to have been a four-game series in three days, including a doubleheader. But because of a May rainout, the Sox added a second doubleheader. Then game two of the opening doubleheader was called after five innings because of fog, with the score 1–1. So Boston was compelled to add a third straight doubleheader. But the second game of the second doubleheader also ended in a useless 1–1 tie, called after nine innings due to September’s early dusk.

As for the four games that counted: They split ’em. So after playing six games in three days, the Red Sox and Yankees ended up right where they’d started: Boston up a half-game, with a critical rained-out game still to be made up somehow.

New York unwittingly provided a solution.

The season was supposed to end with the Sox playing four games in New York the second weekend in October. But the Yankees had rented out their home field, Manhattan’s Hilltop Park, to the Columbia University football team that Saturday, leaving them with a game of their own to reschedule. There was already a season-ending doubleheader scheduled for Monday (remember—no games on Sunday). And each team needed all day Thursday, and then some, to reach New York by train from the Midwest (the Sox from Chicago, the Yanks from St. Louis). So New York agreed to move their orphaned Saturday home game to Boston and combine it with the remaining makeup game in a doubleheader.

When the climactic weekend finally arrived, the Sox still had a half-game lead. (New York had played three fewer games, which would not be made up.) The upshot: New York and Boston ended up with what amounted to a best-of-five playoff series with a 1–2–2 format. Game 1 was in New York on Friday, games 2 and 3 were in Boston on Saturday, and games 4 and 5 were back in New York on Monday.

Although they were the home team for the opening game, the Yankees were just as wrung-out as the Red Sox. In fact, having reached New York just three hours before the first pitch, the Yankees stuck with their dark blue road uniforms. Still, New York had one major advantage: 40-game winner Jack Chesbro was on the mound. When it was over, Chesbro was a 41-game winner. Playing on a day cold enough for overcoats, the sluggish Red Sox made three costly errors and New York cashed in for a 3–2 win. The Yankees leapfrogged into first, and jubilant New York fans carried Chesbro off the field.

The rivals reconvened in Boston at one o’clock Saturday afternoon. With a doubleheader sweep, New York could’ve clinched the pennant. And maybe that’s what enticed Yankees manager Clark Griffith into a tactical blunder. Chesbro started the first game, less than 24 hours (and a late-night train ride) after he had just won the tensest game of his life.

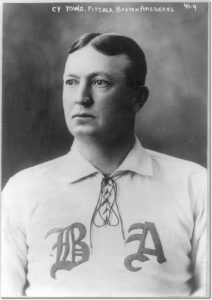

Bad move. Boston chased Chesbro with a six-run fourth en route to a 13–2 rout. And the Sox refused to let up; there wasn’t even a break between games. As soon as Bill Dinneen (22–14) fanned Yankees leadoff man Patsy Dougherty to end the first game, Dougherty had to step right back into the box against Cy Young (25–16) to start the second game. Young wriggled out of several jams in a gripping 1–0 victory.

So it all came down to the season-ending doubleheader back in New York on Monday. Griffith started Chesbro again for the opener. Boston’s fourth starter, Norwood Gibson, was due up next in Sox rotation. But manager Jimmy Collins decided to bring back Dinneen on short rest.

The Yankees struck first, with two runs in the fifth. The rally included a key hit by Dougherty, the left fielder. He had been a vital member of the Sox team that had beaten the Pirates the year before in the first World Series. But with his average down almost 60 points, the Sox had dealt him to New York in June. Since then Dougherty had haunted his old mates, hitting .381 with nine extra-base hits in sixteen games against Boston.

It was still 2–0 in the seventh when New York became unnerved against the bottom of the Boston order. First baseman Candy LaChance led off with a single. Then Yankees second baseman Jimmy Williams couldn’t handle a hot grounder by his Sox counterpart, Hobe Ferris. It was scored a hit, putting runners at first and second. Catcher Lou Criger sacrificed the runners over. Collins left Dinneen (a .208 hitter) in the game, and he rolled a grounder to Williams. Instead of taking the force-out at first, Williams fired the ball to the plate. It eluded catcher Red Kleinow and rolled to the backstop, allowing the tying runs to score.

It was still 2–2 starting the ninth. Criger led off with an infield single and advanced to third on a sacrifice and a groundout. Sox shortstop Freddy Parent needed a hit to drive him in. Unless the Yankees decided to help the Sox cause again.

They did. Chesbro had achieved his 41 wins through deft use of the spitball, a legal pitch at the time. But the wet one worked against him at the worst possible time. He sailed a pitch over Kleinow’s head, and the Red Sox scored their third run, all on balls to the backstop.

But the drama of the 1904 pennant race wasn’t over yet. In the home half, a pair of walks put runners on first and second with two out. In stepped Dougherty, Boston’s friend-turned-nemesis. With the count 2–2, Dinneen fired a waist-high fastball over the inside corner. Dougherty swung and missed—“the last man out in the most important game of ball ever played,” declared the Globe’s T.H. Murnane.

Outlasting the Yankees for the pennant was its own reward. There was no World Series in 1904—nor was there an informal one that season, thanks to the shortsightedness of the New York Giants. The National League champions haughtily declared that they saw no purpose in playing the champion of “a minor league.”

Rob Sneddon’s new book, Boston’s 100 Greatest Games, is available in books stores and on-line—you can purchase it from Amazon by clicking HERE

About the Author

Rob Sneddon is a contributing editor at Down East magazine and a sports historian. In addition to the four major sports, he has written about everything from candlepin bowling to dirt-track racing. (Sneddon’s account of the first Daytona 500, “A Flying Start with a Photo Finish,” published in Speedway Illustrated magazine, was included among the Notable Sports Writing of 2008 in the Best American Sport Writing anthology.)

Sneddon has ridden across America on a bicycle and flown around the world on a record-setting flight aboard the Concorde. But his favorite place remains New England, with its rich (and often forgotten) sports history. In addition to obvious shrines like Fenway and the Garden, Sneddon enjoys visiting obscure landmarks like Columbia Field in North Attleborough, where Walter Johnson pitched to Jim Thorpe in the remarkable Little World Series of 1919, and the Colisee in Lewiston, Maine, site of the 1965 world heavyweight championship fight between Muhammad Ali and Sonny Liston.

He lives with his wife and son in New Hampshire.

We all know why the NL refused to play the AL Champs… That “minor league” team beat Mugsy’s Giants the year before. So, who were the real bush leaguers McGraw?

Correction, 1903 Boston beat the Pittsbugh Nationals. Regardless, McGraw couldn’t cope with losing again.