Fans of the Boston’s Braves and Red Sox might enjoy spending some time exploring the images housed in the “Sports Temples of Boston” portion of the Boston Public Library’s website. Specific sections are devoted to events at the baseball “temples” of the Congress Street Grounds, South End Grounds, Huntington Avenue Grounds, Fenway Park and Braves Field. A large quantity of nostalgic photographs of famous and obscure representatives of the Hub’s National and American League ball clubs populate these categories. If you’ve attended games at Fenway Park the past few seasons, you may have seen examples from this collection offered for sale at a table staffed by the library at one of the park’s concourses.

Fans of the Boston’s Braves and Red Sox might enjoy spending some time exploring the images housed in the “Sports Temples of Boston” portion of the Boston Public Library’s website. Specific sections are devoted to events at the baseball “temples” of the Congress Street Grounds, South End Grounds, Huntington Avenue Grounds, Fenway Park and Braves Field. A large quantity of nostalgic photographs of famous and obscure representatives of the Hub’s National and American League ball clubs populate these categories. If you’ve attended games at Fenway Park the past few seasons, you may have seen examples from this collection offered for sale at a table staffed by the library at one of the park’s concourses.

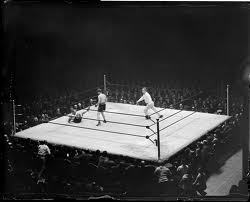

However, limiting one’s search to the baseball locales will prevent you from witnessing a photo from one of the more notorious happenings involving a first baseman and a backstop with ties to the Boston Braves. Buried among the photographic images in the Boston Garden section of the “Temples” area on the website is a shot of the infamous Shires-Spohrer fight of January 10, 1930.

Although the bout was on the under-card of a main event that featured local rival heavyweight contenders Ernie Schaaf and Al Friedman, the duel between the two ballplayers was clearly of primary interest to the packed crowd of the recently opened Garden. Arthur “The Great” Shires was a first sacker with the White Sox at the time. He would later be picked up by the Braves for the 1932 season. Al Spohrer was a catcher for the Tribe from midseason 1928 through 1935. He played all but two of his eight-season, 756-game big league career with Boston. The combating pugilists were teammates in Boston for one season.

Shires’ braggadocio manner and fiery temper rendered him unpopular with fans, opponents and even teammates. Twice in 1929, Shires had taken a poke at his manager, Lena Blackburne, a former infielder who had put in a brief appearance with the 1919 Braves.

Shires’ boxing career was controversial to say the least. Before his meeting with Spohrer, Shires had refused a call from the Illinois Boxing Commission to answer “diving” allegations leveled against a previous opponent described by contemporary newspaper accounts as a “self-confessed trained seal.” Rumors of mob involvement in the outcomes of Shire’s fights also emerged. He had once been photographed before a White Sox game at Comiskey Park shaking hands with Al Capone. The National Boxing Association suspended Shires in the 32 states under its jurisdiction. Since Massachusetts was not a member of the national association, he was free to fight in the Bay State.

In reality, Al Spohrer was a substitute for a more important baseball quarry being pursued by Shires. He had sent out a challenge to future Hall of Famer Hack Wilson but failed to net a match. Wilson’s fighting was confined to the diamond as Cubs president Bill Veeck, Sr. had forbidden his outfielder from stepping into the ring against a Windy City American League rival. Wilson also had been unimpressed by Shire’s taunt as the Pale Hose first baseman recently had received a sound thrashing in the ring at the hands of Chicago Bears’ center and future Pro Football Hall of Famer George Trafton in a fight sarcastically described in the press as the “Battle of the Clowns.”

According to Braves’ owner, Judge Emil Fuchs, the stimulus for Spohrer’s ring appearance was the catcher’s wife. Apparently, Mrs. Spohrer desired a lifestyle requiring an income beyond the salary derived from her husband’s services behind home plate. Such was her hunger for ready cash that she’d appear at the club’s Braves Field office on paydays to grab his payroll check. Sympathetic Tribe management, aware of his spouse’s proclivities, would arrange to slip the check to Spohrer in advance of her arrival.

Despite accepting the challenge from a more experience fighter, Spohrer believed that his opponent’s reputation was suspect. He picked up on the history of Shire’s questionable contests and intimated that some may have been set-ups. Through his public statements, the Tribe backstop questioned the Chisox first baseman’s skills inside the ropes. Spohrer commenced to train seriously for the battle and let it be known that he sparred with 1927-29 Light Heavyweight Champion Tommy Loughran and that the latter failed to lay a glove on him. Judge Fuchs remarked, “Spohrer talked so convincingly that many of the boys were ready to back him to the limit.”

True to form, Al Spohrer remained a “catcher” within the squared circle. At the opening bell, his opponent attacked with a wild swinging barrage that forced the bald-headed backstop into a clinching strategy for the remainder of the contest. In the second round, Shires dropped Spohrer for a nine-count with a right hook to the head. The Braves catcher spent the rest of the round covering up in a neutral corner. In a brief moment of glory, Spohrer bloodied Shires’ lower lip with a light jab in the third round.

Spohrer’s handlers threw in the towel in the fourth after a number of Shires’ wild right hands landed on their target, who was unable to retaliate. The technical knockout was “The Great’s” fourth ring victory in five outings. According to ringside statisticians, Shires landed 87 blows versus Spohrer’s 27 hits. The Garden crowd vigorously jeered the victor.

In the main event, Schaaf was awarded a victory on points over Friedman. Over the course of their careers, Schaaf and Friedman had met four times previously with Schaaf always prevailing in a similar manner. Both pugilists were ill-fated. In a December 13, 1926 bout against 1924 French Olympian Charles Peguilhan, Friedman, a Roslindale native, rallied in the final round to knock out his opponent. The 21-year-old Peguilhan, appearing in his first U.S. bout, died from his injuries the next day. At age 26 in 1934, Friedman would be struck and killed by a hit-and-run automobile driver.

Ernie Schaaf, originally from New Jersey, but who fought out of Wrentham, MA, was a top-ten contender who fought the heavyweight division’s elite. In a 1932 contest against Max Baer, he received a severe beating but avoided an official kayo. The aftereffects of that bout, followed by a knockout loss to Primo Carnera six months later sent Schaaf into a coma from which he never emerged. He was 24 at the time of his death.

Shortly after the Spires-Spohrer fight, baseball commissioner Kennesaw Mountain Landis summoned Shires to his office. The commissioner provided the ballplayer-boxer with an ultimatum — quit the prize ring or quit baseball. According to Landis’s edict, “Hereafter any person connected with any club in this organization who engages in professional boxing will be regarded by this office as having permanently retired from baseball. The two activities do not mix.” As The Washington Post reported, “Charles Arthur Shires today lost a one-round decision to Kennesaw Mountain Landis.”

It may seem a bit incongruous given the history that the Braves acquired the abrasive Shires from the American Association Milwaukee Brewers for the 1932 season. Both the White Sox and Senators had given up on him despite batting averages well above .300. A seventh place finish the year before and anemic team hitting — last in the league in batting average, runs scored, slugging percentage and on-base percentage — can cause a team’s management to overlook a player’s apparent flaws.

Perhaps, also, the perceived bad blood between Shires and Spohrer might have been exaggerated. It was said that in agreeing to the bout, Shires was sympathetic to the financial plight of Spohrer and that “Art the Great” had even sent a bouquet of flowers to Mrs. Shires to ease the pain of her husband’s defeat. A friendship seemed to have developed between the former adversaries to the extent that they were scheduled to be roommates. Nevertheless, evidence of “Shires being Shires” emerged at the Tribe’s spring training camp in St. Petersburg. Upon reporting, Shires commandeered Spohrer’s locker, posting a note on its door that read, “I knocked you on your ass in Boston and now claim all rights, title and interest in your locker.”

Shires’ time with the Braves was limited by injuries. He appeared in only 82 games and batted an uncharacteristic .238. His performance reflected a debilitating knee injury that effectively ended his time in the big leagues at the tender age of 25. Shires tried and failed to make the team the following year and spent 1933-35 toiling in the minors before calling it quits. His last assignment was as a playing manager of the Braves’ Harrisburg Senators New York-Pennsylvania League affiliate where he directed the club to a sixth place finish in a seven-team circuit. Shires’ post-organized baseball life continued to be colorful involving, among other things, more boxing matches, a messy divorce, operating a restaurant/bar, a failed run for the Texas House of Representatives and a murder charge that eventually was reduced to simple assault. For a much more detailed review of his colorful life, the reader is directed to Shire’s biography appearing in the Society for American Baseball Research’s Biography Project at

http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/e1c5d177

Shires died of lung cancer in 1967 at 60 years of age.

Al Spohrer led a much quieter life than the man that he met in the ring in 1930. After breaking in with the New York Giants for a couple of games in 1928, he spent the remainder of his career with the Braves, primarily as their regular backstop. In addition to his venture into the ring in 1930, Spohrer had his best season in the majors that season, batting .317 in 112 games. In his final season of 1935, he was briefly a teammate of Babe Ruth’s during the Bambino’s abbreviated final appearance as an active player. The Braves’ acquisition of Al Lopez in December led to the end of Spohrer’s days in Boston and the majors.

Al Spohrer led a much quieter life than the man that he met in the ring in 1930. After breaking in with the New York Giants for a couple of games in 1928, he spent the remainder of his career with the Braves, primarily as their regular backstop. In addition to his venture into the ring in 1930, Spohrer had his best season in the majors that season, batting .317 in 112 games. In his final season of 1935, he was briefly a teammate of Babe Ruth’s during the Bambino’s abbreviated final appearance as an active player. The Braves’ acquisition of Al Lopez in December led to the end of Spohrer’s days in Boston and the majors.

He eventually divorced the wife that precipitated his fight with Shires and remarried. Spohrer spent his post-baseball years in Plymouth, NH, working as a field representative for a national company. He died in 1972 after a brief illness. Spohrer was 69 at the time of his passing.

Hi Robin,

Phil Cassenetti of Sportsworld in Saugus is the biggest and most reputable baseball memorabilia dealer in New England. I,m not sure if this piece is in his sweet spot but he will know where you should go.

Herb Crehan