Sometimes the good old days weren’t nearly as good as we would like to think. But as you will read in Dick Trust’s wonderful story, sometimes they were even better!

There was a time not so long ago when a young baseball fan could ride in a taxi to Fenway Park with a couple of major league ballplayers.

I know because I was a young fan who did so.

Early in the 1959 season, as in the previous two or three years, my friends and I staked out the Hotel Kenmore in Boston for the noble purpose of getting the autographs of the visiting players who were in town to face the Red Sox.

We needed to get every player on each of the other seven American League teams that came to Boston and stayed at the Kenmore. If you were a true teenage collector, you had to have the whole team – from the bona fide stars known to even the casual fan to a rookie called up for just the proverbial cup of coffee and known only to a limited few in the city they visit.

We’d wait outside for most of the players, and occasionally stroll into the hotel lobby or peek into the coffee shop for any stray players who hadn’t yet come out. You could tell a ballplayer by the way he walked, with a certain swagger, a confidence built through the years as he climbed the ladder from deep in the minor leagues to the majors.

We recognized most of the veteran players through baseball cards, newspaper and magazine photos, from TV or, the best way, by seeing them in person before. “Hey, it’s Rocky Colavito. Hi, Rocky, can I have your autograph?” If we didn’t know them, and they swaggered, we’d just go up and ask for their autographs without addressing them by name and then checking out the signature to see who they were.

Occasionally we’d guess wrong. We’d walk up to a guy, ask for his autograph, he’d smile and then say, “I’m not a ballplayer. Sorry.” Ninety-nine percent of the time he’d be telling the truth. Once in a great while, a guy we did not recognize who really was a player would trick us with that “I’m-not-a-ballplayer” schtick. But that was rare.

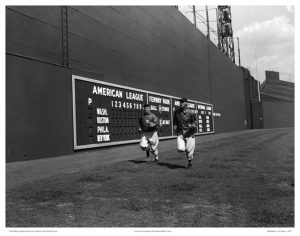

Ballplayers in the 1950s usually walked the short distance to Fenway, maybe a 10-12 minute walk. Some would walk straight to the park in the conventional manner, up Commonwealth Avenue to Brookline Avenue to Lansdowne Street and into the ballpark. Others would take a shortcut, going down a side street, cutting through a fence, crossing the railroad tracks that later were paved over and became the Mass. Pike and then reaching the park.

Often, when we knew all of the players were out of the hotel, we’d walk to Fenway with the last player or two, making small talk but feeling so big because we were talking to Reno Bertoia or Jim Brideweiser or, if we were really lucky, Harmon Killebrew or Bob Turley.

Once at the park, we’d wait outside the gate with our tickets in hand. When the ushers were given the signal, the gates would fly open; we’d go through the turnstiles and rush in to the third base grandstand seating area because that’s where most of the foul balls landed during batting practice. By and large, the balls were stained with green (from grass) or brown (dirt) and scuffed by the time they struck wooden seats and rolled around. When they hit the seating area, a mad scramble ensued and only the swift and most cunning among us were able to secure a batting practice baseball.

Most of the baseballs that wound up in the seats were not caught in the air. That would endanger tender, little teenage hands. Most were line drives that smacked against the seats with great force or high pop-ups that would land on a concrete step or aisle and bounce before the chase was on. In four years of such adventures – going to most of the summer home games and arriving early for batting practice – I managed to outfox my buddies and snare 22 baseballs. We would use them for autographs after erasing dirt marks and trying our best to cover up grass stains.

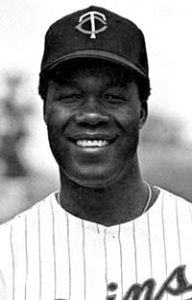

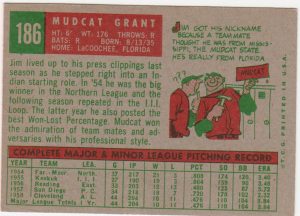

Meanwhile, back at the Kenmore, two visiting Indians players remained, and out they came: pitchers Jim “Mudcat” Grant and Humberto Robinson. I approached them both as they walked out of the hotel and easily secured their autographs by just extending my index cards with the appropriate photos on them.

Grant, the more outgoing of the two, asked if I were going to the game. I said I was, and before you could say “Humberto Robinson,” Mudcat asked if I’d like to join them in a taxi for the short hop to the ballpark. Before you could say “Mud,” I said, “Really? OK, sure!”

Robinson got in the back seat and I sat next to him. Mudcat – I addressed him as “Jim” – sat up front, next to the driver. There was some small talk going on, mostly between “Jim” and me. Jim turned around and asked me a few questions, the exact wording lost in the passage of 55 years. Could it be that long ago?

Before you could say “we’re here,” we were there. We all got out, Jim paid the cab driver, and we stood at the gate. Jim said, “Do you want to come in with us and then go find a seat?” Do bears love honey? “Sure,” I said. We all walked in, Jim telling the gate attendant, “He’s with us.” I beamed.

The two players stood for a moment and I thanked them for the ride. Jim said, “Glad you could come. Have fun.” I shook their hands goodbye. “Good luck today,” I said. They smiled and walked toward the visitors’ clubhouse. Good guys. Robinson, unfortunately, died in 2009 at age 79. Grant is still with us; he’ll be 79 in August.

It was about 2½ hours before the 2 p.m. first pitch, so I headed for the left field grandstand and was there before the gates opened, before my baseball-chasing friends would start rushing up to the magic seats.

Batting practice was under way. A short while into it, I saw Mudcat standing in the dugout, looking toward the left field grandstand. “He’s looking for me,” I said to myself. I walked toward the dugout, toward Mudcat Grant. I waved to him and he saw me immediately. He motioned for me to come down to the dugout. I zigzagged my way through the rows of seats and reached Mudcat just as he was reaching for something on the bench.

He showed me a small, square box, opened it and handed me a brand-new, shiny baseball. No mud from a Delaware river had been rubbed onto it. It practically sparkled and would be a great ball for autographs. I must have thanked Mudcat five or six times before rushing back to my friends. I was the envy of all of them because of that perfect little sphere.

To a bunch of kids who owned mostly scuffed-up baseballs that had ricocheted off wooden seats and rough concrete steps, a brand-new baseball – from a major league pitcher, no less – was bound to create wonderment.

I told them my taxi story, the cab ride from heaven. A lot of mouths dropped open in awe. “Really?” was one reaction. “Whoa, luck-ee,” was another. Yeah, lucky. Really. No dirt to erase, no grass stains to cover up. A baseball right out of the box. That’s as good as it gets.

Dick Trust covered sports for The Patriot Ledger of Quincy, Mass., for 40-plus years before retiring in 2006. Now a freelance writer and photographer, Dick lives in Scituate, Mass. His limited-edition, coffee-table book of never-before-published photos, Ted Williams: Newly Exposed, is available by contacting him at rtrust68@comcast.net Each copy of the book is $49.95 plus shipping. Dick will sign each book upon request.

Leave A Comment