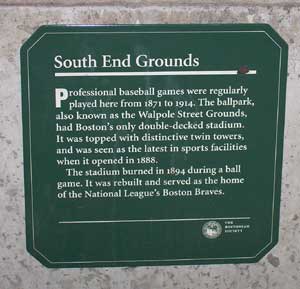

When the Boston Braves left the field at the South End Grounds on Tuesday, August 11, 1914, the glorious opening chapter of professional baseball in Boston passed into history without notice. After a frustrating 13-inning, 0-0 tie with the Cincinnati Reds, all that mattered that day was that the Braves had fallen a half-game behind the second-place St. Louis Cardinals in their quest to track down John McGraw’s league-leading New York Giants.[1]

When the Boston Braves left the field at the South End Grounds on Tuesday, August 11, 1914, the glorious opening chapter of professional baseball in Boston passed into history without notice. After a frustrating 13-inning, 0-0 tie with the Cincinnati Reds, all that mattered that day was that the Braves had fallen a half-game behind the second-place St. Louis Cardinals in their quest to track down John McGraw’s league-leading New York Giants.[1]

There would always be another game tomorrow, although the forecast for the next day’s contest seemed somewhat dubious for Boston cranks contemplating a trip via the Tremont Street streetcar to the city’s South End. Fans of the franchise had been making a similar journey for decades, first by horse-drawn car, then by electric streetcar.[2]

For the South End Grounds, the third iteration of a ballpark on the same city block, however, tomorrow never came. Major-league baseball was never again played on the 4½ acre site.[3]

With Wednesday’s game postponed because of rain, the Braves left town the next day on an extended road trip, never to return to the location that served as their home for longer than any other facility in the more than 140-year history of the franchise. Upon their return to Boston in September, FenwayPark, less than two years old and still sparkling, beckoned. After the Braves started the following season in Fenway with the permission of their American League cousins, in August 1915, Braves Field would become the team’s new home.

Over the course of the South End Grounds’ more than 43 years of service, baseball, the nation, and the city of Boston had all changed dramatically. At the South End Grounds, these forces of change were marked both on the field and in the stands.

Today, many aspects of the first National Association of Base Ball Players game at the site on May 16, 1871, between the Boston Red Stockings and the Troy (New York) Haymakers would seem bewildering, if not downright amusing.[4] The pitcher stood in a box some 45 feet from home and delivered the ball by means of a straight-armed submarine style motion to a batter who could both call for his preferred pitch height and, if he didn’t like them, foul pitches with impunity. His catcher had no mask and typically stood several feet behind home, hoping to “[catch] the ball on its first bounce.” The pitcher wore no glove; neither did any of his fielders.[5] This was baseball as the game was played by the first of its “major” professional leagues in a largely agrarian nation six years removed from a debilitating Civil War.

Over the next four decades the sport transformed itself, reflecting the fluidity of a country entering a dynamic new age of industrialization. Despite many detours along the way, by August 1914, the game had taken on nearly all of its fundamental character, as the flickering celluloid images of that era primitively attest.

At the same time, the city of Boston was growing exponentially, swelling its ranks from 250,526 (seventh largest in the country) to 670,585 (fifth) in 1910.[6] Immigrants of every stripe filled its streets, particularly the baseball-mad Irish, who during this time transformed City Hall from a bastion of Yankeedom into a virtual Irish colony.

During this era of chaotic change, Boston’s baseball franchise was a source of stability and success. Indeed, for most of this period, baseball had one constant. Boston was its king.

And the South End Grounds were figuratively, and for six sweet years literally, its palace.

The South End Grounds: Home of the Braves

(and the Red Stockings, Red Caps, Rustlers, Beaneaters, and, while we’re at it, even the Doves)

Having seen their various amateur baseball squads suffer ignominious defeats at the hands of the professional Cincinnati Red Stockings in 1870, Boston baseball enthusiasts sprang into action after the Red Stockings disbanded once their 87-game winning streak was snapped by the Brooklyn Atlantics. In January 1871 a corporation known as the Boston Red Stockings Club was capitalized to the tune of $15,000. Ivers W. Adams was selected president, but more importantly, George and Harry Wright were recruited to put the team together, a task that they (Harry in particular) accomplished with ultimately alarming success. Harry persuaded a number of former Cincinnati teammates to join him in Boston, but his true ten-strike was signing pitcher Al Spalding from the Forest Citys.[7]

The grounds for this new team were located along the border between Boston’s South End and the newly annexed town of Roxbury, which had become part of the city of Boston in 1868.[8] The site was rectangular in shape, bounded on the east by Berlin Street (which was later incorporated into Columbus Avenue), and by the tracks of the New York, New Haven, and Hartford Railroad (Providence Division) to the west.[9] The railroad proved to be a harsh neighbor. “Passing trains could be counted on to periodically rain smoke and cinders down on the third base patrons and on the field itself,” a baseball historian has written. “If the wind was right and the traffic was heavy, games were halted in order to allow the haze generated by the trains to clear.”[10]

A Providence and Boston Railroad roundhouse was situated to the north of the playing field, and Camden Street lay beyond that. The southern perimeter was marked by a narrow passage known as Walpole Street, giving rise to the frequently used alternative appellation for the park: The Walpole Street Grounds. “Although a concession stand was in evidence from the beginning, rest rooms were not.”[11] The park was also known as the Union Baseball Grounds, BostonNationalLeagueBaseBallPark, or the Boston Base Ball Grounds.

Whatever name was used, the playing grounds were unusual in shape. Left field (250 feet) and right field (255 feet) were extremely close to home plate, and a compensating huge center field (450 feet) gave the park many of the characteristics of the bathtub-shaped Polo Grounds. It was said the park was “like a bowling alley. It only had one field: center.”[12]

The grounds were at first leased from the railroad and its associated structures were quite simple. “The pavilion looked like a big volunteer fireman’s carnival booth.”[13] This covered seating area “was of simple design and resembled many of the parks of the era. The main grand stand was quite boxy, containing approximately twenty five rows of seats under the cover of the overhanging roof. The roof was held up by six supports.”[14] “Four rows of primitive box seats and a smaller wooden bleacher section sat in front of the grand stand behind a three foot wooden fence.”[15] Fifty cents brought admission to the grandstand, while a quarter was all that was required to sit in the uncovered “bleaching seats” that paralleled the basepaths. Standing room was plentiful, particularly in the generous confines of center field. At first the park was surrounded by a 12-foot-high wooden fence. Two ticket booths stood guard on Walpole Street, directly across the street from the groundskeeper’s house.[16]

South End Grounds gate

In these rather modest surroundings, the Red Stockings successfully began their professional odyssey in a match against a picked nine on April 6, 1871, before a packed house. “[A] full five thousand persons … the largest number ever assembled before in these grounds” were on hand, with some standing on top of the fence and others watching from rooftops.[17] With Spalding pitching, the professionals defeated the opposition 41-10, thereby establishing two long-term local institutions: on-field success and inventive attempts to avoid paying the entrance fee.

With Spalding leading the way, the Bostons swept to four consecutive National Association titles between 1872 and 1875. In his signature season of 1875, Spalding posted a record of 54 wins and only five losses. Boston’s one-sided dominance of the National Association was a major factor in its eventual collapse. William A. Hulbert of Chicago became the driving force behind the newly formed National League.[18]

A Shift in the Balance of Power

At its core, this change represented a massive shift in power from players (in the National Association of Base Ball Players) to clubs and their owners (in the National League of Base Ball Clubs). Hulbert was also the driving force in luring Spalding along with three other Boston star players to Chicago: second baseman Ross Barnes, former catcher turned outfielder/first baseman Cal McVey, and catcher Deacon Jim White. When these “Four Seceders” came to Boston on May 30 for their first game in Chicago White Stocking uniforms, the Boston Globe reported that there had “never been so great a crowd at any base ball match ever played in this country, certainly not in this city.”[19] The crowd of between 10,000 and 12,000 spectators, which the Globe described as “almost appalling,” literally tore down the fences at the South End Grounds, according to one account.[20] The Four Seceders won that day, 5-1, and their defection led to a pennant for Chicago and a frustrating fourth-place Boston finish (a mere eight games over .500, landing the team in the middle of the eight-team field) in the National League’s inaugural season.

The consequences of the passage of power to the owners were reflected quite clearly at the South End Grounds. By 1876 the presidency of the Boston club was vested in the hands of Nathaniel Taylor Apollonio, who was not shy about endorsing an exciting new method of protecting the security of the gate. In a postcard ad for the Washburn & Moen Manufacturing Co. of Worcester, Massachusetts, the Red Stockings president sang the praises of that company’s barbed-wire fence. Installing it atop the wooden fencing “increased the size of [the] gate from $400 to $500” on the first day it was utilized.[21] Interestingly, the postcard ad also features opaque screening strung along the first-base side above the perimeter fencing in an apparent effort to thwart nonpaying spectators watching from “wildcat bleachers” on neighboring rooftops. The battle against these so-called “dead heads” was well and truly under way. It would escalate to near epic proportions in the years to come.

Three Cheers for the Triumvirs?

On-field success in the form of a pennant returned with impeccable timing to Boston in 1877, coinciding as it did with the rise of the so-called triumvirate (typically shortened to Triumvirs) of Arthur H. Soden, James B. Billings, and William H. Conant to power. According to franchise historian Harold Kaese, “Boston’s threesome wielded fully as much power in the National League as their predecessors did in the Roman League and they survived to live considerably longer and happier lives.”[22] At first, Boston’s fans could also not have been happier, as the Triumvirs brought immediate successive pennants with them to power and secured, during the span of their collective careers, a total of eight championships.

The Triumvirs, however, had a schizophrenic quality about them. They were innovative and, upon occasion, more than willing to open their collective wallets in pursuit of glory. A prime example was the acquisition of slugger and speedster Michael “King” Kelly from Chicago in 1887 for the astounding sum of $10,000. The following season Kelly was joined by pitcher John Clarkson, a fellow refugee from Chicago. This so-called “$20,000 battery” was showcased in the magnificent brand-new grandstand built by the Triumvirs.[23]

Although team president Soden is forever remembered as the originator of the hated reserve clause, his game-changing, free-spending approach to the practice of buying big player contracts is virtually forgotten. Truth be told, this is due to the fact that the Triumvirs were notorious penny-pinchers. “Complimentary tickets were virtually unknown,” and “players were encouraged to enter the stands and wrestle fans for foul balls.”[24] On one occasion Soden “ripped out the press box to make room for more paying customers. Players’ wives had to buy tickets to get in.”[25]

Even worse, when it came to public relations, the Triumvirs were profoundly inept. For example, when team profits declined from $120,000 in 1897 to $90,000 in 1898, team treasurer Billings lamented: “We lost thirty thousand dollars last year.” In 1905 president Soden told manager Fred Tenney: “We don’t care where you finish so long as you don’t lose money with the team.”[26] Ironically, when other teams in the League did lose money, Soden frequently provided the cash to keep other teams (and the league) afloat.[27]

Nonetheless, the relationship between fans and ownership soured over time, resulting in a “sorry exit” when the team was sold in 1906.[28] Before that occurred, the South End Grounds and its surrounding environs experienced a roller-coaster ride of highs and lows.

Sullivan’s Tower

Despite, or perhaps because of, their team’s successes on the field, the Triumvirs were in an almost constant battle against outlaw “dead head” spectators attempting to avoid the price of admission. The rooftops of the adjoining city streets presented an economic opportunity for enterprising individuals who were amenable to hosting large groups of visitors. At the forefront of this band of hardy entrepreneurs was one Michael Sullivan, who lived behind right field on Berlin Street, near Burke Street. His “roost,” more commonly known as Sullivan’s Tower, was constructed level by level over time in lockstep with the efforts of the Triumvirs to block the view. Sullivan’s Tower was “an architectural monstrosity”[29] that grew over time into a Boston landmark.[30] In the view of many, “Sullivan’s Roost was as much a feature of a National League game in Boston as the contest itself.”[31] In its day, Sullivan’s Tower was as prominent and well known as the CITGO sign in modern-day Boston; in fact, one lyrically inclined fan penned a poem in tribute to the tower that was published in the Boston Globe.[32]

The tower had originally been built “upon the roof of a stable, but [was later] strengthened and braced and made a separate structure.”[33] The passage by the state legislature of Chapter 374 of the Acts of 1885 gave new teeth to the authority of building officials to address issues of public safety in structures of all types. Thus empowered, local officials visited or “raided” (in Sullivan’s view) the edifice. Efforts to declare it unsafe under the new law failed, however, and a subsidiary effort to challenge the lack of a permit for its construction met with a similar lack of success.[34] Ironically, at one point, the Boston Globe reported that Soden’s rather poorly constructed fence “was either blown down or helped down,” and that same morning a satisfied Sullivan was observed perched on his grandstand smoking a pipe.[35] Soden quickly rebuilt.In 1887 an adventurous Globe reporter paid over his 15 cents and made the trek up Sullivan’s Tower. The story unfolds: “At first it was an obscure staging, modestly peeping over Mr. Soden’s fence. Mr. Soden’s fence was raised a few feet one day, and the next day another story had been added to Mr. Sullivan’s staging.” And so, on (and up) it went.

At 80 feet in height, the roost was more than double the height of the surrounding buildings. The staging was “honestly built of good timber enough of which has been employed in its construction to amply satisfy the most exacting of building inspectors,” and thus compared favorably to Mr. Soden’s rebuilt fence, which, incredibly, was nearly as high as Mr. Sullivan’s Tower, and not nearly as well constructed. “If both were let alone the roost would be standing a dozen years after the pickets of the fence had been blown to the four winds by the blasts of springtime.”[36]

As time went on, and levels were added, the viewing platform of Sullivan’s Tower diminished in size. Nonetheless, it is difficult to credit accounts that “as many as 500 fans climbed [Sullivan’s Tower] to see a game.”[37] By 1887 the most recent “addition” to the roost, while adding eight feet of height, cut the viewing platform in half from its earlier 30 feet square. About 30 spectators were present for the late-season game attended by the Globe reporter, in a year in which the Bostons finished fifth.

South End Grounds II: The Grand Pavilion

The end of the 1887 season brought the curtain down on the first iteration of the South End Grounds. In September the Triumvirs announced plans to build a new facility on the site at Walpole Street.[38] The initial cost estimate was reported as $25,000.[39]

The decision was long overdue. The old familiar grounds were the only site “unchanged since the beginnings of the National Association”[40] and Soden had promised to rebuild the “shoddy grounds” as far back as the conclusion of the 1883 season, when a surprising pennant run had set new attendance records.[41]

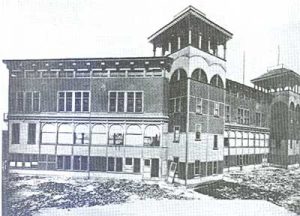

It was worth the wait. Designed by Philadelphia architect John Jerome Deery, the new grounds consisted of an elaborate two-tiered, curving grandstand, complete with a series of towers featuring conical “witches caps.”[42] The Grand Pavilion, as it came to be called, “resembled a medieval castle or fairground.”[43] The Boston Herald proclaimed it a “grand stand unequaled for beauty and convenience in the country.”[44]

![]() The grandstand was almost never built as originally conceived. Although architect Deery assured the Triumvirs during their negotiations that the cost “would not exceed $35,000,” hard cost estimates were considerably higher and, upon opening, “the actual cost [was] reported at [$]70,000.” Nonetheless, the Herald reported that “the idea of abandoning the plan of having a new stand was not entertained for a moment.” The question was whether to forge ahead or to build a less elaborate and less expensive structure instead. Not surprisingly, the Herald claimed it had influenced the outcome directly by pressuring the Triumvirs through the publication in mid-September 1887 of an elaborate description of Deery’s master plan, complete with three drawings.[45] Just days prior, the Globe had publicized its estimate that the Triumvirs had made $100,000 during the 1887 season alone.[46]

The grandstand was almost never built as originally conceived. Although architect Deery assured the Triumvirs during their negotiations that the cost “would not exceed $35,000,” hard cost estimates were considerably higher and, upon opening, “the actual cost [was] reported at [$]70,000.” Nonetheless, the Herald reported that “the idea of abandoning the plan of having a new stand was not entertained for a moment.” The question was whether to forge ahead or to build a less elaborate and less expensive structure instead. Not surprisingly, the Herald claimed it had influenced the outcome directly by pressuring the Triumvirs through the publication in mid-September 1887 of an elaborate description of Deery’s master plan, complete with three drawings.[45] Just days prior, the Globe had publicized its estimate that the Triumvirs had made $100,000 during the 1887 season alone.[46]

Pressured or not, the Triumvirs went ahead despite the enormous costs. Optimism for the coming campaign abounded. In early April the Boston Globe published a cartoon entitled “Winning Cards” featuring a poker hand containing Clarkson, Kelly, and the new grandstand as three of the cards, predicting: “With this combination, the Boston Nine should be able to win a pennant and make a small fortune for the Triumvirs.”[47]

The semicircular grandstand seated 2,800 persons. The lower tier accommodated 2,072 in nine sections labeled “A” (third base) through “I” (first base). Ample provision was made for “reporters and telegraphers” behind home plate. The home clubrooms were located on the first-base side, while the visitors were perched on the third-base side.

The balcony sat an additional 772 in seven sections.[48] Approximately 2,000 seats were also available in each of the two bleacher sections in left field and right field.[49] A Boston Herald account indicated that restaurants were located “on the extreme ends of the pavilion.” “Toilet rooms were provided for the ladies with all the modern improvements.” A concerted effort was made to keep the patrons of the grandstand separate from those sitting in the bleachers. The restaurants were configured so that both grandstand and bleacher patrons could be served “without in any way interfering with each other and neither can any patron of the outside seats obtain, by any subterfuge, admission to the pavilion through the restaurants.” [50]

The ballpark was visually imposing. The “witches caps” sat upon four tulip-shaped columns, two at each end of the curving grandstand.[51] From Walpole Street, the full majesty of the edifice was evident. At either end sat large square brick towers with bays on the corners of their upper reaches. In between rose the central 82-foot brick and terra-cotta tower. The lower 40 feet of the tower were brick, while the upper reaches were made of terra cotta. Ticket offices were located on either side of the central tower. The Triumvirs also completed efforts to widen Walpole Street in order to improve access which provided “a good comfortable entrance” to the ballpark.[52] “While the park was complimented on its architecture … [it was] criticized for its lack of comfort and poor sight lines.”[53]

After a lengthy season-opening road trip, Opening Day festivities on May 25, 1888, were a noteworthy affair, notwithstanding the 4-1 loss to Philadelphia. “Boston’s upper crust, a big slice of the lower crust and a mighty congregation of the intermediate” were on hand.[54] Dignitaries in attendance included former Governor Ames, who thought the game was “more amusing than a session of the Legislature,” and the mayors of both Boston and Cambridge, numerous other elected officials, and the spouses of the famed members of the “$20,000 battery.” Nearly 15,000 fans were in attendance, more than doubling the new park’s 6,800-person seating capacity. The chill east wind made some spectators miserable, “but still it was a great game – for the management.”[55] The season held true to this form, with the Beaneaters finishing fourth but drawing more than an estimated 300,000 paying customers to the new grandstand, bringing smiles to the faces of the Triumvirs.[56]

Those smiles truly blossomed in 1891 when second-year manager Frank Selee of Melrose, Massachusetts, and his talented roster, including Clarkson, Kelly, and pitching star Kid Nichols, took the first pennant in eight seasons home to Boston. It was the first of three consecutive pennants for the Bostons. Attendance, which had slipped as low as 147,539 in 1890, had climbed back to 193,300 by 1894.[57] While their success on the field could not be imitated, the short-lived (one year) Boston franchise of the upstart Players League had, in 1890, taken a cue from the Grand Pavilion. The club “spared no expense in planning for the new pavilion for their Congress Street Grounds” since any “baseball park [was] now incomplete without a grand pavilion,” in the view of the Boston Globe.[58]As 1894 dawned the Triumvirs were indeed baseball’s kings, ruling from their grand castle. What could possibly go wrong?

The Great Roxbury Fire of 1894

As visually striking as the Grand Pavilion was (despite its poor sightlines and uncomfortable seats), its tenure as Boston’s home grounds was brief and its end spectacular. Constructed of wood, it is unsurprising that its end came by fire. Indeed, 1894 saw a series of fires at ballparks in Baltimore, Chicago, and Philadelphia as well as Boston. Some believed that “the fires were being set deliberately, and some went so far as to hint that Sabbatarians” were to blame, seeing in the fires a conspiracy to stop Sunday baseball, which the National League had sanctioned in 1892.[59]

No such conspiracy was at work in the South End, although the precise cause of the fire on May 15, 1894, was (and perhaps remains) a matter of some dispute. The New York Times believed the fire was caused by “some small Roxbury boys” who had “set themselves up as rivals to Mrs. O’Leary’s cow.”[60] The Boston Herald concurred in this probability.[61] The more widely accepted account, appearing in the Boston Globe, told of a carelessly disposed match falling upon sawdust and timbers beneath the stands.[62]

A rotting portion of the center-field bleachers had been removed during the offseason and workers had left sawdust and debris behind, under the right-field seats.[63] Curiously, the detailed description of the careless smoker was provided by 14-year-old James Laskey who had, in the two nights following the fire, not returned home. He had been “bunking out … just to see how it would seem.”[64] Just as remarkably, the Boston Herald noted that the “bleachers were boarded underneath and there was no interstices, so that it would be an impossibility for a person to drop a match or cigar to the ground.”[65] Despite the somewhat questionable veracity of this youthful witness, Laskey’s account was embraced by most. As a result, “all theories and suspicions of incendiarism [were] wiped from the minds” of property owners and city officials.[66]

The fire began during a league match between Boston and Baltimore, in the third inning. Noticing the flames, Boston right fielder Jimmy Bannon tried to stomp out the fire with his feet. He was unsuccessful. The wind apparently shifted and “the fire roared to life.”[67] The game was halted. The fire would dictate that day’s winners and losers.

Within an hour, 12 acres were destroyed, 1,900 people were made homeless and the grandstand, “the handsomest in the country” in the opinion of Sporting Life, had been forever lost in the second worst fire in the history of the city of Boston.[68] The Triumvirs chided the Boston fire department (and police) for a slow response to the danger. Indeed, the Boston Herald concluded that there was one reason for such an extensive loss: “Somebody Blundered.”[69] John Haggerty, the groundskeeper, tried valiantly to sound the alarm and appeared to be “the only man who acted with any sense,” perhaps befitting a man whose home lay across Walpole Street from the burning grounds.[70]

The franchise faced a crisis on two fronts. The immediate need to find a place to continue the still-young season was solved starting the next day by the use of the Congress Street Grounds. Located near a pier in South Boston, these were the former home grounds of the city’s Players League and American Association teams.[71]

The second problem was more complicated. The Grand Pavilion and its associated facilities were worth $75,000, according to Triumvir Conant, but according to a list of insurance claims published two days later, the facilities were insured for only $45,000.[72] The Triumvirs were severely criticized for underinsuring the Grand Pavilion and for the consequences that this underinsurance portended for the rebuilt ballpark.

In point of fact, the Triumvirs were hardly unique in their plight. Initial estimates (subsequently revised upward) pegged total losses from the fire at $300,000, only half of which was insured. The city of Boston lost both a school and a fire department “hose house” in the blaze. Neither the school nor the hose house was insured. According to one H.R. Turner of the Niagara Insurance Company, the fire, while “deplorable from a humanitarian standpoint,” would “hardly be felt by the insurance companies,” due to small tenement houses in the area. Very few “of these occupants carr[ied] any insurance.” Then, in a statement callous enough to have come from one of the Triumvirs, he concluded: “The fire could not have happened in a locality more advantageous for insurance interests.”[73]

One thing was certain. The long-running competition between the Triumvirs’ fence and Sullivan’s roost was over. “[T]he fire played no favorites. It leveled them both.”[74]

While the criticism of Triumvir penny-pinching with insurance colors the subsequent discussion of the disappointing results of their rebuilding effort, a plausible case for caution could be made. In 1894 the country was in the midst of a severe recession following the Panic of 1893; indeed, employment would not return to 1891 levels until 1900. As a result of “the disruption in the financial system, some nonfinancial businesses found it difficult to obtain the funds they needed to meet payrolls and were forced to suspend operations.”[75]

Thus, the Triumvirs – who after all had been willing to spend the money to construct the Grand Pavilion despite horrendous cost overruns – may have pulled back on their reconstruction efforts due to their lack of faith in the ability of other enterprises to keep paying (and employing) potential fans.

A more pointed – and irrefutable – criticism of ownership appeared in Sporting Life. The weekly chastised the Triumvirs for failing to properly police up the months-old debris in the area, and for even more egregiously failing to provide for a fire hydrant or a fire hose to be maintained on site. This “‘pennywise and pound foolish’ method of management” left the club unprepared for the preventable tragedy that unfolded.[76]

South End Grounds III: Is It Better to Burn Out Than to Fade Away?

The combination of a lack of insurance proceeds and a lack of confidence in the overall economy produced a rebuilt ballpark on a smaller scale than its majestic predecessor. What was impressive was that it was built at a breakneck pace. The Bostons defeated New York in the rebuilt grounds before 5,206 fans on July 20, barely two months after the fire.[77]

The new grandstand was a modest, single deck structure with “twin spires … suggestive of the Churchill Downs racetrack”[78] and a seating capacity of 900. The number of bleacher seats was increased to compensate for this shortcoming. “[T]he only stands in the outfield were a small set of bleachers in [right field] called the pie bleachers because they were triangular shaped, like a piece of pie.”[79] “Although not as impressive as the old building, the new park had more comfortable seating and better sightlines.”[80] Its seating capacity was approximately 5,000.[81]

Within a year the inadequacy of the rebuilt grounds had become apparent and the push to upgrade the facility began. In 1895 two iron wings were added, bringing the grandstand’s seating capacity to 2,300.[82]

The addition was timely; the Beaneaters rebounded to win consecutive pennants in 1897 and 1898, ending the three-year dominance of the Baltimore Orioles.[83] Thereafter, the team’s fortunes receded and in 1906 the Triumvirs sold the team to George and John Dovey, who had partnered with a “theatrical man named John Harris.”[84] It was a poor investment decision for the new owners. The Beaneaters finished last for the first time in franchise history in 1906, the South End Grounds were in disrepair – “an ugly little wart” in the words of one description – and there was a new team in town.[85]

Five years earlier, the American League’s Boston team [as of the 1908 season, known as the Red Sox] had, through the maneuverings of Connie Mack, among others, taken up residence literally on the other side of the tracks. The Huntington Avenue Grounds, built in 1901, were bordered by the New York, New Haven, and Hartford Railroad on the east, a mirror image to the South End Grounds’ western boundary. The American League “park was new, neat, and larger than the South End Grounds, of which the public had grown weary.”[86] The price of admission was half that at the National League park. Little wonder, then, that on the date of the upstart league’s inaugural home opener, they outdrew the Nationals substantially. With the benefit of at least 70 “jumpers” from the National League, by 1902 the American League was outdrawing the National League by some 300,000 fans.[87] Among the fans attracted to the new Boston team was saloonkeeper Michael “Nuf Ced” McGreevey. McGreevey (and his Royal Rooters) had originally been supporters of the Beaneaters, and a version of the slogan for his Third Base Saloon had adorned the left-field wall at the South End Grounds.[88]

The Dovey brothers’ major contribution to the physical facility at Walpole Street was the construction of new outfield bleachers for the 1908 season, although they had also supplied a new scoreboard the year before.[89] A 40-foot-wide strip across the outfield was dedicated to the new seating, with an open space retained in the vicinity of the flagpole in center field. Overall seating capacity grew to 11,000.[90] When George Dovey died suddenly, his brother John ultimately took his stead, but soon the team was sold to a syndicate headed by William H. Russell. In less than a year Russell, too, was dead and the “Doves” who had briefly become the “Rustlers” were again in search of new ownership.

In December 1911 the team was sold to a new troika of leaders, headed this time by Tammany Hall hard-charger James E. Gaffney, the club’s treasurer. The franchise soon acquired a new nickname – derived from the term “Sachem,” which was used to describe the leader of Tammany Hall – the Braves.

Gaffney immediately set out to improve the tired South End plant.[91] Based on the recommendations of co-owner John Montgomery Ward, a series of changes to the configuration of the South End Grounds were put through. Given the permanence of its urban boundaries, the grounds had always retained its rectangular configuration. Green Cathedrals reports its dimensions at LF 250 (1894), LC 445, Deepest LC 450, CF 440, Right Center 440, RF 255.[92] The addition of outfield bleachers in 1908 decreased the straightaway left-field, left-center-field and center-field dimensions by between 38 and 43 feet.[93]

Ward’s changes involved removing the left-field bleachers, adding another section to the grandstand and shifting the diamond toward right field to bring “the foul line over the left-field fence at a distance of 350 feet or more than 100 feet farther down the field than at [the] present time.”[94] However, the 1912-1914 left-field dimension is reported in other reputable sources as 275 feet. The 350-foot distance description quoted above was provided by Tim Murnane of the Boston Globe, himself a former ballplayer, and has the ring of authenticity. The contemporary accounts of the Boston Post and the Boston Herald confirm that this indeed was the plan.[95]

The record nonetheless is not perfectly clear. Sporting Life first reported in February that “the task of changing around the old South End Ground is greater than was at first supposed” and then in March reported “that the fielding space is increased about 15 feet.”[96] Murnane tells a different story. His Opening Day 1912 account reported that all 10,000-plus spectators “enjoyed the many changes made at the park, the transformation giving about 25 percent more room for hitting.”[97] Finally, Harold Kaese, author of the seminal history of the franchise in Boston, also reports a 350-foot left-field distance in 1912.[98]

In right field, what was happening was indisputable. The firm of Waitt and Bond, manufacturer of the well-known Blackstone cigar, erected a modern cigar factory (reputed to be the world’s largest) at 716 Columbus Avenue.[99] The factory building, which still stood in 2013, loomed over the grounds from the opposite side of the street. Kaese wrote that Jay Kirke, a powerful left-handed hitter whose fielding was less than graceful, often launched fly balls in that direction, frequently followed by the sound of tinkling broken glass. Eventually the factory was closed and a new facility opened in New Jersey.[100]

Gaffney also made numerous cosmetic improvements to the Grounds, painting the entire plant “green with crimson trimmings” so that the facility “altogether present[ed] a very attractive appearance.”[101] “The walks to the field seats on either side of the field [were] relaid in blue stones” improving the park’s appearance so much that “[o]ld time patrons of the park [would] not know the place. … More money [was] spent on decorations than the Triumvirs ever spent in their lives on such things.”[102]

Gaffney was in a state of perpetual motion. In the fall of 1913, he acquired a parcel at Columbus Avenue and Walpole Street that would allow for the existing grandstand to be demolished, the playing field to be enlarged, and a new modern grandstand erected.[103] In mid-January of 1914, Gaffney was reported to be returning to Boston the next week to review bids for a new concrete grandstand.[104] He also installed a new scoreboard in deep center field at the start of the 1914 season.[105]

Standing on the threshold of a major financial commitment to the four-decades-old location, Gaffney hesitated. The fateful, wonderful miracle season of 1914 began.

The End of Days

It was success that ultimately spelled the end of the South End Grounds. The maniacal climb of the Miracle Braves flooded the facility beyond its capacity. By early August 1914, Red Sox president Joseph Lannin, who had only just previously acquired a small stake in the Braves franchise, put FenwayPark at the disposal of the Braves without charge.[106] Gaffney, ever the cagey politician, initially accepted only for Saturday and holiday game days.[107] Upon their return from the road, the Braves played a Labor Day morning-afternoon doubleheader against the Giants in Fenway. Nearly 75,000 attended the two games, and the Braves never returned to the South End.[108] For the 1914 season, the combination of access to Fenway and a baseball miracle for the ages lifted Braves attendance to 382,913, first in the National League.[109]

Gaffney never looked back. Frustrated by an undersized facility plagued by “clouds of smoke from the locomotives [that] interfered with the play and the comfort of the spectators,”[110] he scoured the Boston area for sites that would accommodate his vision of a playing field unencumbered by urban boundaries. He found just such a location on the site of a former golf course, bounded ironically by the same harsh neighbor – the railroad – that he had fled the South End to avoid.

When Gaffney’s Braves moved from the Walpole Street facility, they were obliged to sell the grounds subject to an “iron bound agreement” that the land could not be used for baseball, an effort to block the grounds from falling into the hands of the Federal League.[111] And so the Braves left the familiar confines of the South End, despite the fact that to that time “[m]ore championships [had] been won on those old grounds than on any other in the world.”[112]

Taking the grass from their infield with them, the Braves moved on. Moving to the expanse of Braves Field, however, “was like moving from a modern three bedroom apartment into a nineteenth century mansion.”[113] The franchise was never the same, appearing in only one World Series in nearly four decades in Allston.

Today the site of the old South End Grounds barely countenances a memory of its storied past. The railroad is still there, in the form of the Southwest Corridor, and Columbus Avenue and the old cigar factory both have tales that they could tell. Now owned by NortheasternUniversity, most of the field is occupied by surface parking and a garage. But if one goes just north beyond the garage, in the area where the old railroad roundhouse once stood south of Camden Street, there lies a trio of modest playing fields. Two of the fields are framed by small wooden stands and a larger array of concrete and aluminum seating sits there quietly as well, providing at least a distant echo to the cheers from the bleaching boards of the late 19th century.

This chapter appears in a wonderful new book: The Miracle Braves of 1914: Boston’s Original Worst-to-First World Series. To order a copy of this book go to:

Or you may purchase a copy through Amazon.

[1] J.C. O’Leary, “13 Zeros Apiece,” Boston Globe, August 12, 1914, 7.

[2] In 1896, Chickering Station on Camden Street was closed. Prior to that time, the station was also heavily trafficked by baseball fans.

[3] Ronald M. Selter, Ballparks of the Deadball Era (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2008), 20.

[4] This was the date of the first National Association match. The first match between the Red Stockings and a picked nine took place on April 6 of that year and is described below.

[5] Harvey Frommer, Primitive Baseball (New York: Atheneum, 1998), 61-68 (describing changes in the game from the mid-1870s to the new century).

[6] census.gov/www/through_the_decades/fast_facts (retrieved June 15, 2013).

[7] Harold Kaese, The Boston Braves 1871-1953 (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2004), 5, 7.

[8] Sam Bass Warner, Jr., Streetcar Suburbs, The Process of Growth in Boston (1870-1890) (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1962), 41.

[9] Alan E. Foulds, Boston’s Ballparks and Arenas (Lebanon, New Hampshire: Northeastern University Press, published by the University Press of New England, 2005), 8. (The New York, New Haven, and Hartford Railroad leased the Old Colony Railroad in 1893, which by that time included the Boston and Providence Railroad.)

[10] Bill Felber, A Game of Brawl (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007), 60.

[11] Foulds, Boston’s Ballparks and Arenas, 8-9.

[12] Michael Benson, Ballparks of North America (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 1985), 39.

[13] Benson, Ballparks of North America, 39.

[14] Foulds, Boston’s Ballparks and Arenas, 8-9.

[15] Benson, Ballparks of North America, 39.

[16] Foulds, Boston’s Ballparks and Arenas, 8-9.

[17] Kaese, The Boston Braves, 9.

[18] Hulbert’s bold maneuvering to establish the National League is described in detail in Michael Haupert’s fine SABR biography, at sabr.org/bioproj/person/d1d420b3.

[19] Boston Globe, May 31, 1876, 1.

[20] Kaese, The Boston Braves, 19.

[21] Michael Gershman, Diamonds: The Evolution of the Ballpark (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1993), 29.

[22] Kaese, The Boston Braves, 22. The First Triumvirate of Rome was a political alliance between Gaius Julius Caesar, Marcus Licinius Crassus and Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (Pompey the Great). Crassus died in battle approximately seven years into the alliance, whereupon Caesar and Pompey fought a civil war. The survivor, Caesar, ultimately was assassinated on the Senate floor.

[23] Sporting Life, April 11, 1888, 1.

[24] Kaese, The Boston Braves, 47, 23-24.

[25] Benson, Ballparks of North America, 39.

[26] Kaese, The Boston Braves, 113, 111.

[27] Brian McKenna’s SABR biography of Soden makes for entertaining reading on the extraordinary life of this Triumvir. sabr.org/bioproj/person/a1b2e0d0.

[28] Besides their own miserliness and constant financial clashing with the team’s human capital [the players], the Triumvirs’ demise was hastened by poor on-field performance and the introduction of competition in the form of the American League in 1901.

[29] Kaese, The Boston Braves, 68.

[30] Peter Morris, A Game of Inches: The Stories Behind the Innovations that Shaped Baseball: The Game Behind the Scenes (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2006), 429.

[31] Lewiston (Maine) Evening Journal, July 29, 1914, 9.

[32] Boston Globe, July 10, 1889, 5.

[33] Boston Globe, August 1, 1885, 3.

[34] Boston Globe, August 20, 1885, 4.

[35] Boston Globe, August 19, 1887, 8.

[36] Boston Globe, September 5, 1887, 4.

[37] Donald Hubbard, The Heavenly Twins of Boston Baseball (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2008), 109.

[38] Boston Herald, September 16, 1887, 5.

[39] Boston Globe, August 19, 1887, 8.

[40] Foulds, Boston’s Ballparks and Arenas, 13.

[41] Kaese, The Boston Braves, 37.

[42] Unlike FenwayPark, which has evolved into a double-deck structure, the Grand Pavilion was designed and built as a two-tier facility, the only such structure in Boston baseball history.

[43] Foulds, Boston’s Ballparks and Arenas, 15.

[44] Boston Herald, May 25, 1888, 5.

[45] Boston Herald, May 25, 1888, 5.

[46] Boston Globe, September 12, 1887, 8.

[47] Boston Globe, April 8, 1888, 1.

[48] Boston Globe, May 25, 1888, 5.

[49] Lowry, Green Cathedrals, 108.

[50] Boston Herald, May 25, 1888, 5; for a fascinating discussion with Tom Shieber of the Baseball Hall of Fame describing the Classic Ballpark Tours interactive exhibit featuring the South End Grounds, see: Paul Ferrante, “Travel Back in Time to Boston’s South End Grounds,” August 20, 2012, sportscollectordigest.com. Retrieved June 24, 2013.

[51] Lowry, Green Cathedrals, 43.

[52] Boston Globe, May 14, 1888, 8.

[53] Foulds, Boston’s Ballparks and Arenas, 15.

[54] Boston Post, May 26, 1888, 2.

[55] Boston Globe, May 26, 1888, 4.

[56] Tim Murnane, “Hub Happenings,” Sporting Life, October 3, 1888, 7.

[57] Baseballalmanac.com/teamstats/roster. Retrieved July 15, 2013.

[58] Boston Globe, February 23, 1890, 22. For an excellent history of the Congress Street Grounds, readers are directed to Charlie Bevis’s ballpark biography of that facility, at SABR.org/bioproj/park/33169c79.

[59] Gershman, Diamonds: The Evolution of the Ballpark, 53. Sunday baseball in Boston would remain controversial for decades.

[60] New York Times, May 16, 1894, 1.

[61] Boston Herald, May 16, 1914, 1.

[62] “Was a Match,” Boston Globe, May 18, 1894, 1.

[63] Foulds, Boston’s Ballparks and Arenas, 19.

[64] Boston Globe, May 18, 1894, 1.

[65] Boston Herald, May 17, 1894, 3.

[66] Boston Globe, May 18, 1894, 1.

[67] Paul Ferrante, “The Most Beautiful Ballpark Ever?” August 9, 2012, sportscollectordigest.com. Retrieved June 24, 2013.

[68] Sporting Life, May 26, 1894, 3.

[69] Boston Herald, May 16, 1894,1.

[70] Boston Post, May 16, 1894, 3.

[71] Philip J. Lowry, Green Cathedrals (New York: Addison-Wesley, 1992), 108.

[72] Boston Globe, May 18, 1894, 4.

[73] Boston Globe, May 16, 1894, 5.

[74] Kaese, The Boston Braves, 68.

[75] Mark Carlson, “Causes of Bank Suspensions in the Panic of 1893,” Federal Reserve Board (2002), federalreserve.gov/pubs/feds2002/200211pap.pdf. Retrieved June 11, 2013.

[76] Sporting Life, May 26, 1894, 5; Sporting Life, June 2, 1894, 1.

[77] Foulds, Boston’s Ballparks and Arenas, 19.

[78] Felber, A Game of Brawl, 60.

[79] Selter, Ballparks of the Deadball Era, 18.

[80] Foulds, Boston’s Ballparks and Arenas, 19.

[81] Selter, Ballparks of the Deadball Era, 18.

[82] Tim Murnane, “Building Iron Wings,” Boston Globe, January 13, 1895, 16.

[83] Frommer, Old Time Baseball, 107.

[84] Kaese, The Boston Braves, 115.

[85] Kaese, The Boston Braves, 101, 113.

[86] Kaese, The Boston Braves, 101.

[87] Frommer, Old Time Baseball, 60.

[88] Gershman, Diamonds: The Evolution of the Ballpark, 75.

[89] Kaese, The Boston Braves, 115.

[90] Tim Murnane, “Bleachers in Center Field,” Boston Globe, January 7, 1908, 5.

[91] Gaffney also once and for all provided the team with an enduring nickname. He chose the name Braves in deference to the Sachem, the symbol of his Tammany Hall. Previously, the franchise had been known as the Red Stockings, Red Caps, Rustlers, Beaneaters, and the Doves, as well as simply the Boston Nationals.

[92] Lowry, Green Cathedrals, 109.

[93] Selter, Ballparks of the Deadball Era, 20.

[94] Tim Murnane, “Ward’s Field Changes to Be Put Through,” Boston Globe, January 20, 1912, 7. By the end of July 1912, John Montgomery Ward had sold his stake in the team, resigning as its president. Gaffney became the new president of the franchise.

[95] Boston Post, January 20, 1912, 13; John J. Hallahan, “To Make Over South End Park,” Boston Herald, January 20, 1912, 6.

[96] Sporting Life, February 12, 1912, 7; March 30, 1912, 3.

[97] Tim Murnane, “Boston Braves Play to 10,264,” Boston Globe, April 12, 1912, 1.

[98] Kaese, The Boston Braves, 129.

[99] Moody’s Manual of Railroads and Corporation Securities: Volume 2 (New York: Poor’s Publishing Company, 1921), 728.

[100] Kaese, The Boston Braves, 125-6.

[101] Boston Globe, March 26, 1912, 6.

[102] Sporting Life, April 6, 1912, 7.

[103] Sporting Life, October 18, 1913, 2.

[104] Sporting Life, January 17, 1914, 14.

[105] Sporting Life, April 25, 1914, 7.

[106] Sporting Life, November 29, 1913, 3.

[107] Sporting Life, August 8, 1914, 3.

[108] Sporting Life, September 26, 1914, 8.

[109] baseball-reference.com. Retrieved June 5, 2013.

[110] A.H.C. Mitchell, “The World’s Champions,” Sporting Life, December 26, 1914, 3.

[111] Tim Murnane, “Baseball Exit for South End Grounds,” Boston Globe, December 20, 1914, 15.

[112] Sporting Life, December 26, 1914, 3.

[113] Kaese, The Boston Braves, 173.

As a lifelong Boston resident and Red Sox season ticket holder, this was a great read with some facts that were both amusing and intriguing. It was interesting to read about the progression of ballpark design improvement. The quest for better sightlines and fan comfort continues to this day.

Thought I knew a lot!.. Thankyou for sharing this important fruit of your research.

Fences 250 feet from home? Submarine/underhand pitches from the mound? I could have been an 1871 Red Stockings superstar! Thanks for providing such fantastic visuals of these old ballparks. With the descriptions of the bleachers, outfield fences, and ballpark dimensions, I felt like I was sitting right there in the stands. Great Neil Young reference too….keep these articles coming!

Thanks Chris!

Bob Ruzzo deserves all of the credit.

I hope you keep coming back!

Herb Crehan