Ask a casual fan of the Boston Red Sox what they remember about the sixth game of the 1975 World Series against the Cincinnati Reds and the answer is certain to be, “Pudge Fisk’s game-winning, twelfth-inning home run.” Ask a dedicated, long-term Red Sox fan the same question and the answer is likely to be, “Bernie Carbo’s eighth-inning home run that tied the game, and set up Fisk’s home run.”

Bernie Carbo immediately perks up at the mention of one of the most dramatic home runs in Red Sox history. “When I got to home plate after that home run, my teammates mobbed me and the fans were going crazy. It wasn’t until I got to the dugout that I found out I had tied the game. I was so focused on keeping the inning alive that I hadn’t paid any attention to the score. The fans were screaming my name. I think I could have been elected the Mayor of Boston.”

BORN TO PLAY

Bernie Carbo was born in Detroit, Michigan, and grew up in suburban Detroit. “When I was 11 years old we moved to NankanTownship. My dad found a house right across from EdwardHinesPark so I could play ball all the time. I was over there from morning to night.”

Bernie developed the beautiful “inside-out swing” that he used to great affect at FenwayPark on the diamond of Edward Hines. “We usually only had eight or nine kids, so anything hit to right field was an out. I was the only left-handed hitter and the kids refused to switch around when I came up. It forced me to learn how to hit the ball to left field.”

Bernie’s Little League career began with a home run. “Our coach was a woman. She was a good coach and a nice woman. First time up I hit a ball that went between the outfielders. I slid into second base, I slid into third base, and then I slid into home plate for a home run.”

Bernie was a good all-around athlete in high school, but baseball was his passion. “I think I always wanted to be a baseball player growing up. Whenever we had to do a book report, I would make up a baseball story. It was always about the Detroit Tigers and they always went to the World Series. I imagined myself as the star of the team. I never actually read the books, I just made them up.”

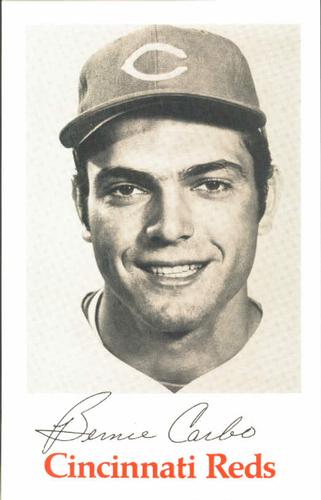

The first baseball amateur free agent draft was held in 1965 when Bernie Carbo was 17 years old. A favorite baseball trivia question in Cincinnati is: “The second player selected by the Reds in the first free agent draft was Johnny Bench. Who was the first player ever drafted by the Reds?” The answer is: Bernie Carbo.

“When I reported to Tampa after signing with the Reds, I was being interviewed by a sportswriter, and another player came over and asked me if I was the first draft choice. I told him I was. Then he asked me how much I signed for. When I told him, ‘$30,000,’ he shook his head and walked away. I asked the writer who the player was, and he said, ‘Johnny Bench. And he’s upset that he only got $5,000.’”

SPARKY ANDERSON

Bernie Carbo had a tough time during his first few seasons in the minor leagues. “I was just a kid and I felt a lot of pressure, being the number one draft choice. I responded to the pressure by clowning around, making my teammates laugh.”

Hall of Fame manager Sparky Anderson was making his own way through the minors and he took Bernie Carbo under his wing in 1968 at Ashville, North Carolina. In his autobiography, Sparky (Fireside: 1990), Anderson recalls working with Bernie Carbo. “I may have spent as much time working with Bernie Carbo as any player I ever managed. When I first met him his teammates called him “The Village Idiot” and he liked it. I had Bernie out to the park every morning, hitting him fly balls and working on his hitting.”

Bernie is quick to credit Sparky Anderson with salvaging his career. “He had me out there at 9 a.m. every morning. He moved me from third base to the outfield where I was more comfortable. He taught me to take the game seriously.”

The following season Bernie hit .359 at Indianapolis, the Reds’ top farm team. His outstanding season earned him recognition as the Minor League Player of the Year. A strong showing in the Puerto Rican Winter League and a good spring training propelled him to the Cincinnati Reds for the 1970 season.

THE CINCINNATI KID

“My first hit in the big leagues was a home run on Opening Day in Cincinnati. It was the longest home run in baseball history. I hit it out of the park onto Route I-75. It landed in a truck and they found it in Florida, 1,300 miles away. It was a great way to start my big league career.”

Carbo stayed hot all through his rookie season, finishing with a .310 average and 21 home runs. The Sporting News named him the National League Rookie of the Year. But controversy found him when the Reds faced the Baltimore Orioles in the World Series.

“I was on third base with one out. Ty Cline tops a ball in front of the plate, and I break for home. I had to push the umpire [Ken Burkhart] out of the way to get to home plate. Elrod Hendricks [Baltimore catcher] never tagged me. I missed home plate, but I stepped on it when I went back to argue.

“Sports Illustrated got a great picture of the play that they ran for years. It shows Hendricks tagging me with his glove but the ball is in his right hand. Every time I see Earl Weaver [former Orioles manager] he says, ‘You’re still out, Bernie.’”

Controversy followed Bernie into the 1971 season when he deemed the Reds’ contract offer inadequate and declined to report to spring training. His lack of pre-season training and his disillusionment with the Reds resulted in a drop in his batting average of almost 100 points, to .219 for the 1971 season. Bernie sat out spring training once again in 1972, and in May the Reds traded him to the St. Louis Cardinals.

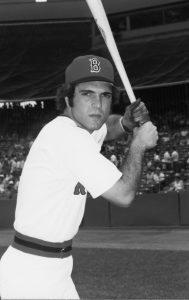

Bernie played parts of two seasons with the Cardinals. Following a productive 1973 season in St. Louis, he was traded to the Boston Red Sox along with pitcher Rick Wise in exchange for Reggie Smith and Ken Tatum.

A GOOD ITALIAN BOY

“Boston was a big adjustment for me,” Bernie Carbo recalls. “In Cincinnati we might have had two or three writers in the clubhouse. When I got to Boston for Opening Day, it seemed like there were 100 writers covering us. One writer says to me, ‘Bernardo Carbo, you must be Italian.’ ‘No,’ I told him, ‘I’m Spanish.’ I pick up the paper the next day and I read, ‘Bernardo Carbo, a good Italian boy, joined the Red Sox yesterday.’”

It also took Bernie Carbo a while to sort out all of the faces in the Red Sox clubhouse. “Right after I joined the team I walked into the clubhouse and there was an older gentleman straightening things up. I gave him $20 and asked him to get me a cheeseburger and some french fries. When the clubhouse kid delivered the food, he asked me if I knew who I gave the $20 to. I told him I didn’t, and he said, ‘You just asked Tom Yawkey to get your lunch.’ I thought I was in big trouble, but Mr. Yawkey got a big kick out of it.”

Bernie played well in 1974 and quickly became a fan favorite. A former Cardinal teammate sent him a stuffed gorilla, which Carbo named “Mighty Joe Young,” and took with him on road trips. Eminently quotable, The Boston Globe’s Clif Keene once wrote, “Bernie Carbo could talk for twenty minutes about a spool of thread.”

A SEASON TO REMEMBER: 1975

When Bernie Carbo reported to spring training in Winter Haven, Florida, in February 1975, he had no idea that the upcoming season would be one of the most celebrated years in Red Sox history. “I knew we had a lot of talent,” Bernie said in a recent interview, “but I certainly wasn’t thinking about the World Series when training camp opened.

“We had Yaz, Rick Miller, Dwight Evans, and Juan Beniquez coming back with Fred Lynn and Jim Rice joining us after playing in September in 1974. I knew I was going to have to play hard that spring to get a chance.”

Bernie Carbo had an outstanding spring. He batted .325 with two home runs and he played well in the field. Looking back Bernie credits two Red Sox coaches with helping him to prepare. “Don Zimmer [third base coach] knew me and he knew my swing. Zim had managed me in Knoxville in 1967, so he had lots of good advice.

“And Johnny Pesky [first base coach] was so great,” Bernie says. “He always had a smile for me and he knew so much about playing the game. I loved Johnny Pesky.”

Most seasoned baseball observers shared Carbo’s skepticism regarding the Red Sox chances in 1975. The consensus from a poll in the Sporting News was that the team would finish third in the AL East. The Baltimore Orioles were favored to win their third straight AL East title and the Yankees were seen as the strongest contender.

Bernie Carbo’s versatility was a key component in the Red Sox drive to the American League Championship in 1975. He played 85 games in the outfield, served as the designated hitter, and pinch-hit. In just over 400 plate appearances he finished tenth in the American League with 83 walks.

“Playing for Tom Yawkey made all the difference. I loved Mr. Yawkey like a second papa. When I got to Boston I was a disillusioned ballplayer. But then I wanted to play for the uniform, for the team. And for Mr. Yawkey.

“I went to him that season and told him I wanted to buy a house for my family. I asked him to advance me $10,000, and to take it out of my pay. I went to my locker a few days later and he had left a check for $10,000 in there. He never took a dime out of my pay.”

1975 WORLD SERIES

The Red Sox swept the defending World Champion Oakland A’s in three games in the 1975 American League Championship Series. But Bernie Carbo spent the ALCS on the Red Sox bench. After spending the first two games of the World Series against the Cincinnati Reds in the same spot, he was getting a little restless.

“I went into the Reds’ clubhouse when we got to Cincinnati to visit with some of my old teammates. My former roommate Clay Carroll gave me a nice picture inscribed, ‘Good luck in the World Series.’ I told some of the guys that I was tired of sitting on the bench and it was time to get me into the Series. It wasn’t very smart, but I was frustrated.

“Sure enough, in Game Three Darrell Johnson sends me up to pinch hit for Reggie Cleveland in the seventh inning. And who is on the mound to pitch to me? My old roomy Clay Carroll. And don’t I hit a home run into the left field stands?

“When went back to the clubhouse after the game, my locker had been trashed. I asked the clubhouse guy what had happened and he told me that Clay Carroll had stormed in, torn his picture into a thousand pieces and thrown all my things on the floor.”

The Reds won Game Three despite Carbo’s pinch-hitting heroics, but Red Sox ace Luis Tiant came back with a gutsy 163-pitch effort in Game Four. Tiant’s 5-4 victory tied the Series, but a 6-2 Reds’ win the following evening sent the team back to Boston, one game from elimination.

GAME SIX

Rain forced postponement of Game Six for three straight days. The extended break in the Series gave Luis Tiant enough rest to start this crucial game. Fred Lynn raised Boston fan’s hopes with a first-inning, three-run home run to give the Red Sox an early lead. Tiant dominated in the early going, but the Reds tied the game in the fifth inning and moved ahead in the seventh.

Trailing by three runs in the bottom of the eighth, the Red Sox stirred fans’ hopes when Fred Lynn and Rico Petrocelli reached base safely to start the inning. But when Dwight Evans and Rick Burleson were retired, the Reds were only four outs from a World Championship.

“Darrell Johnson told me to grab a bat to pinch hit, but I never expected to bat. The Reds had a left-hander warming up in the bullpen (Will McEnaney) and I was sure they would bring him in. At that point Darrell would have sent Juan Beniquez up to bat in my place. I couldn’t believe it when Sparky Anderson left Rawly Eastwick in to pitch to me.”

To add to the drama, Bernie’s old friend Johnny Bench was behind the plate catching for the Reds. With the count even at 2-2, Eastwick came after Carbo with a wicked pitch on the inside corner. “That was a tough pitch for me to handle,” Carbo remembers. “The ball was almost in Bench’s glove and I just managed to get my bat on it, to foul it off at the last second. Pete Rose (Reds’ third baseman) called it a Little League swing. It was a terrible swing.”

Roger Angell, was more eloquent than Rose in describing Carbo’s swing in his World Series article for The New Yorker. Angell wrote, “Bernie Carbo, pinch-hitting, looked totally overmatched against Eastwick, flailing at one inside pitch like someone fighting off a wasp with a croquet mallet.”

The late Red Sox announcer Ken Coleman had a totally different assessment of Carbo’s performance. “Bernie got a totally un-hittable pitch to deal with, and he managed to get his bat on the ball to stay alive. I thought it was a great piece of hitting. And look at what he did next.”

There is no disagreement about what Bernie did next. Rawly Eastwick did Bernie an enormous favor by coming back with a fastball in his wheelhouse. And Bernie did what he did so well. He turned on it and he drove it straightaway to center with power.

“When I hit that ball, I wasn’t sure if it was going out. I ran as hard and as fast as I could, and I didn’t really slow down even after I knew it was a home run. When I was approaching third base I yelled to Pete Rose, ‘Don’t you wish you were that strong?’ As I was passing him he said, “Ain’t this great Bernie? Isn’t this what playing in the World Series is all about?’

“I just barely got a piece of the pitch before. I turned around after that pitch, and Johnny Bench was jawing with the umpire about whether the pitch would have been a strike. I said to them, ‘Wow. I almost struck out.’ And then I hit the next pitch into the center field bleachers.”

The Red Sox and Reds sparred on into the twelfth inning, when Carlton Fisk hit his dramatic, game-winning home run. The Reds managed a 4-3 win in Game Seven to earn their World Championship, but Bernie Carbo had become a permanent part of Red Sox folklore.

BOSTON TO MILWAUKEE AND BACK

In 1975 most things went right for the Boston Red Sox. They won the American League Championship and they came within one victory of a World Series win. In 1976 hardly anything went right for the Red Sox. Distracted by contract negotiations and the failing health of owner Tom Yawkey, the team got off to a terrible start. On June 3 the team announced that Bernie Carbo had been traded to the Milwaukee Brewers for pitchers Tom Murphy and Bobby Darwin.

“I was devastated,” Bernie Carbo responds, looking back on his trade. “The Boston fans loved me and I loved them back. I couldn’t imagine going from Boston to Milwaukee. My wife at the time was eight months pregnant, and we had two little girls. I was crushed.

“I refused to report to the Brewers. They kept calling, but I told them I couldn’t do it. I could see the light towers at FenwayPark from our place in Cambridge and I just kept staring at them. After about three weeks my wife told me, ‘You have to report. You’re driving me crazy.’ Bud Selig [then the owner of the Brewers and formerly Commissioner of Baseball] flew us all out and I played the balance of the season with the Brewers.”

Bernie’s exile to Milwaukee was relatively brief. On December 6, 1976, Bernie and George Scott were traded back to the Red Sox for first baseman Cecil Cooper. The prodigal son was returning home.

“It was great to go back to Boston. But Tom Yawkey had passed away while I was gone and it wasn’t the same for me. When I heard on the radio that he had died I just cried and cried. I couldn’t stop crying. In some ways I think my career died with Tom Yawkey.”

Bernie Carbo made a significant contribution to the 1977 Boston Red Sox. His on-base average of .409 was the highest on the team, and his 15 home runs in only 228 official at-bats helped the team to set a franchise record 213 round-trippers.

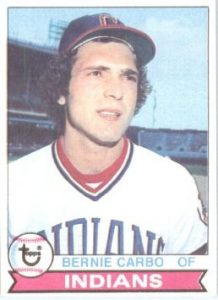

The 1978 Boston Red Sox got off to a great start. By mid-June the Red Sox were 26-4 at home and boasted an overall record of 45-19 for a winning percentage of .703. But manager Don Zimmer was using Bernie Carbo sparingly, and on June 15 the Red Sox announced that they had sold his contract to the Cleveland Indians.

“When I walked into the clubhouse after the game that night, I saw a crowd of reporters around my locker. No one had to tell me what was going on, I knew I was gone. I headed right to my car, still in my uniform, and drove right through the crowd leaving the ballpark. I just had to get out of there.”

WINDING DOWN

Bernie finished out the 1978 season with the Indians, batting .287. In 1979 he rejoined the St. Louis Cardinals, where he was used primarily as a pinch-hitter, and batted .281 for the season. He started the 1980 season with the Cardinals but they released him in May, and he finished the season with the Pittsburgh Pirates. His big league career came to an end when the Pirates released him on October 8, 1980.

“People ask me what I would do if I had my big league career to do over. I tell them the same thing I tell young players today. I tell young players to stay focused and to be the best player they can be. I tell them to stay away from things that can distract you, and don’t make bad choices. I made some bad choices.

“But when I look back on the positive things, I did get to play for 12 years in the big leagues. And I played with some great players, like Yaz and Jim Rice in Boston, I lockered next to Hank Aaron in Milwaukee, and I got play with Willie Stargell in Pittsburgh. I have some great memories.”

LETTING GO

When Bernie’s baseball career was over he started a second career as a cosmetologist. For a number of years he operated a series of beauty salons in the Detroit area.

In 1989 Bernie moved his family to Winter Haven, Florida, where he played for the Winter Haven Super Sox in the newly formed Senior League. The league, which was limited to players over the age of 35, was formed to play in the period between the World Series and the beginning of spring training. His teammates included his long-time friend, former Red Sox pitcher Bill Lee.

The Senior League was not a commercial success and shortly after the league folded Bernie Carbo hit rock bottom. “My mother had committed suicide, my father had died, and my first marriage was coming to an end. Bill Lee called and I told him I wasn’t even sure about the next day. Bill was so concerned that he had Ferguson Jenkins [former Red Sox pitcher] call me and talk to me. Fergie had experienced some personal losses so he knew what I was going through. Then Fergie called Sam McDowell at the Baseball Assistance Team.”

BASEBALL ASSISTANCE TEAM

The Baseball Assistance Team (B.A.T.) was formed in 1986, primarily by a group of former major leaguers, to help members of the baseball “family” who have come on hard times and who are in need of assistance. Joe Garagiola has been their most visible public spokesman, and former Red Sox pitcher Earl Wilson is the President & CEO. Most of B.A.T.’s work is done anonymously, but Bernie Carbo is quick to acknowledge the assistance he received.

“The Baseball Assistance Team probably saved my life. Sam McDowell got me into rehab to get me treatment for my alcohol and drug addiction. And they worked with me for the next three or four years to be sure that I had my life in order and to help me with my finances. I don’t know where I would have been without them.

“While I was in rehab, I had an anxiety attack and they moved me to a regular hospital. I was in a room with an older gentleman and he could tell from the conversations that I was battling addictions. He asked me if I knew God, and I told him I didn’t. He told me that I had to get to know God, and he gave me my first Bible. He really changed my life. When he was leaving I asked him what his name was and he said, ‘The only name you need to know is God’s name.’

“I spent about three months in rehab and when I got out I established the Diamond Club Ministry. I speak primarily to young people about baseball, about Jesus, and about the dangers of addiction to drugs and alcohol. My ministry is non-denominational and I have spoken in Christian churches throughout the United States and all over the world. I have preached in Saudi Arabia and to Cuban refuges at Guantanamo Bay.”

BERNIE CARBO TODAY

“After I had been preaching for a few months I was giving witness at a home for boys and I met this wonderful woman,” Carbo recalls. “I told her, ‘God told me that you need to be with me.’ She told me that God hadn’t told her that. But I persisted, and four months later we were married. She is a very special lady.”

Today Bernie and his wife Tammy live in Theodore, Alabama, just south of Mobile. Tammy, who has a Masters Degree in psychology, is a counselor at the local middle school, and Bernie does some substitute teaching. He has three grown daughters from his first marriage, and his son, Bernie, Jr., who recently received his undergraduate degree, will be pursuing a Masters program. Two of Bernie’s grandchildren live with Bernie and Tammy, and a third grandchild lives in Hawaii.

Bernie Carbo’s Fantasy Camp takes place on the second weekend of November each year. “It’s a fantasy camp for fathers and sons. Last year we had a grandfather, son and grandson participate. We do it as a long weekend, Friday through Sunday, and we keep the numbers down so it will be a meaningful experience for everyone. I have another former major leaguer work with me, and we break the players into three teams. This year we will be doing it at SpringHillCollege in Mobile, Alabama.

Speaking of his previous alcohol and substance addictions, Bernie explains. “My life bottomed out in 1993, and the Baseball Assistance Team literally saved my life, getting me into recovery from my addictions.

“After my recovery I founded The Diamond Club Ministry to help others with addictions and to spread my message of the Gospels. Because of that Game Six home run in 1975 everyone in New England and fans around the country know me,” he says. “And every summer when I come back to New England, doors open to me so I can spread the message of The Diamond Club Ministry and help others.”

Portions of this article originally appeared in Red Sox Magazine. To subscribe to Red Sox Magazine click here.

I was very happy to read about Bernie Carbo and to learn that he is doing so well ! I knew him in the early 80’s and he was a very special guy my friends and I often wondered how he was and if he was ok, good to know that he is fine and so happy that he has over come all his Demons ! Great job Bernie and good luck to you and yours and may God Bless you and keep you well !

I have seen Bernie a lot since his recovery and he is really doing well. August 5 is Bernie Carbo bobblehead night at Fitton Field for the Worcester Bravehearts–you should be able to say hello there.

I may have told you previously, but I met Carbo at the Red Sox Fantasy Camp maybe 20 years ago. I told him that I was at the sixth WS game and saw his home run.

His response: “Ya, you and about 250,000 people,” and he walked away. Maybe he was still in a down phase in his life.

Nonetheless, time to write a new story. My nifty son Matthew called last night to tell me he bought us tix to Game 2 on Wednesday!

Way to go Jerry! I don’t have to tell you how lucky you are to have a son like Matthew. Be sure to bundle up–it gets colder with each succeeding game!

Go Sox!

I grew up and played ball in the same spot as Bernie. Same Hines Park field, same Junior High (Whittier), same High School (Franklin). I was several years behind him and I can recall teachers talking about his enthusiasm for baseball. One social studies teacher, Mr. Baugh, talked about young Bernie popping his glove in the back of the classroom. Another friend of mine, Billy Black, was Franklin’s QB when Bernie played football at Franklin H.S. He says Bernie Catbo was a helluva football player as well.

I went to rival Thurston High and bowled with Bernie at Wonderland Lanes. What a nice kid. When he got drafted I was so proud to know him. I told all my friends what a great athlete Bernie was. Think we were league champs 1964, Thanks for giving me a chance to brag. Congrats on you’re ministry, what an inspiration.