On April 15, 1947, Jackie Roosevelt Robinson started at first base for the Brooklyn Dodgers in a game against the Boston Braves at Ebbets Field in Brooklyn, New York, becoming the first African-American Major League Baseball player in the 20th century. A little over 12 years later, Elijah “Pumpsie” Green entered a game between the Boston Red Sox and the Chicago White Sox on July 21, 1959, at Comiskey Park in Chicago, Illinois, as a pinch-runner and at long-last all 16 Major League Baseball teams had fielded an African-American team member. To this day, 65-years later, the Boston Red Sox still wrestle with the dubious distiction of being the last Major League Baseball team to integrate.

I probably spent more time thinking about the best focus for the Pumpsie Green feature than any other profile I have written for the Boston Red Sox official program. Obviously Pumpsie was the first African American to play for the Boston Red Sox, who were the last major league baseball team to integrate. But that story has been told and retold.

I moved into my teenage years watching the Boston Celtics of Bill Russell and the Jones boys hoist World Championship banners to the rafters of Boston Garden. And while the Patriots were just a glimmer in Billy Sullivan’s eye, we had all watched players of color in the NFL on television every Sunday.

Even the Bruins, in a league where the color of the players invariably matches the color of the ice, had integrated the NHL in 1958 with winger Willie O’Ree. And if you knew your baseball, you knew that Sam Jethroe had been the first African-American baseball player in Boston, playing with the Braves from 1950 to 1952.

For most of us the absence of an African American on the Red Sox was a mystery. Pumpsie arrived in Boston in July 1959 and his career with the Red Sox only lasted through the 1962. We never really got to know Pumpsie Green.

I decided to ask Pumpsie Green to tell us who he really is. I learned that he is a warm, much-loved man, with a nice story to tell. I liked him a lot and wish I had gotten to meet him instead of spending 90 minutes talking to him by telephone at his El Cerrito, California home. I’m sure you will like him as well.

PUMPSIE GREEN

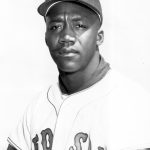

Every story about Pumpsie Green begins the same way. Pumpsie Green was the first African American to play for the Boston Red Sox. He was “the bookend” to Jackie Robinson when the Red Sox became the last major league team to set aside the racial barrier.

But Pumpsie Green was, and is, more than just an important footnote in the history of the Boston Red Sox. He was a three-sport star in high school, a big brother to four younger siblings, and a capable professional baseball player. He was a devoted husband and father, who doted on his granddaughter, and woreds out five-days a week at the local YMCA.

Elijah “Pumpsie” Green never set out to be a racial pioneer. “I just wanted to be a major league baseball player, to make the team. I really got tired of the writers asking me about the situation before I was brought up. People were asking me so many questions about things I had no control over.”

Pumpsie never wanted to be placed in the spotlight that focused on Fenway Park. But he handled the pressure with grace and good nature. He is much more than just a footnote to the history of the Red Sox. He is an important part of who the Boston Red Sox are today.

BAY AREA NATIVE

Elijah Jerry Green was born on October 27, 1933, in Oakland, California. “I was named Elijah after my father, but my mother called me Pumpsie when I was a couple of years old. I used to ask her why she called me that but she never gave me a good explanation.

“Pumpsie is the only name I have ever known. I don’t remember anyone calling me Elijah. Some of my friends today, even the ones I’ve known a long time, I’m not even sure if they know my real name.”

Pumpsie grew up in Richmond, just outside of Oakland, where his father worked for the city. Pumpsie was followed by four brothers, including Cornell who was an All-Pro defensive back with the Dallas Cowboys, and Credell who played for the Green Bay Packers.

“When I was growing up, it seemed as if everyone was playing baseball, all the time. Baseball was a natural part of life where I grew up. All the kids in the area, the young and old, men and women, everybody played baseball.

“I never really played against my brothers, even though they were athletes. They were younger than me and I had my own crowd. I also played mostly against guys that were older than me. When I was ten, I played against guys who were thirteen or fourteen years old.”

He still remembered his first baseball glove and the events leading up to it. “I must have been about eight or nine, and I still didn’t have my own glove. It was at a time when the family really couldn’t afford that kind of expense. But I talked my mother into it and I did work around the house every day. Finally she saved enough money, I think it was seven or eight dollars, and she bought me a brand new glove.

“My hero was Artie Wilson, who played shortstop for the Oakland Oaks, and he wore a three-fingered glove. My mother bought me a three-fingered glove, a Calendonia, and I loved it. I tied the whole thing up into a neat package, oiled it and so forth. I used it, and used it, until I wore it out.”

PACIFIC COAST LEAGUE

In the years immediately after World War II, the quality of baseball played in the Pacific Coast League was just a notch below the major league level. There were no major league teams west of the Mississippi River, and the eight-team PCL circuit stretched from Seattle in the north to San Diego in the south. Fans on the West Coast followed their teams with the passion of big league fans. The 1948 Oakland Oaks, who won their first PCL pennant in 21 years under manager Casey Stengel, were Pumpsie Green’s team.

“The Pacific Coast League was really big. I listened to Bud Foster doing every Oakland Oaks game and followed a whole bunch of guys on that team. It was almost a daily ritual. Artie Wilson was the best thing I had ever seen at that point, but I loved to watch Jackie Jensen and Billy Martin also. When I got old enough to wish, I wished I could play for the Oakland Oaks.”

Like most fans on the West Coast, Pumpsie didn’t follow major league baseball closely as a youngster. “I can remember seeing a big billboard with a picture of Stan Musial on the highway. But that was the only association I had with major league baseball.”

But he does remember hearing about Jackie Robinson integrating major league baseball with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947. “That was very exciting to hear about. After the 1948 season, he barnstormed with an All-Star team and they played in the Oakland Oaks ballpark. I scraped up every nickel and dime I could find. And I was there. I had to see that game with the Jackie Robinson All-Stars. I still remember how exciting it was.”

Growing up he played all sports, but baseball was the most popular sport in his neighborhood. He made himself into a switch hitter as a youngster for an unusual reason. “We played a team from another neighborhood that was our cross-town rival and they beat us 44-0. But we had a rematch, and we said, ‘Hey, let’s do everything the opposite of what we normally do.’

“I was a right-handed hitter, so I turned around and batted left-handed. That moment in time is what began the switch-hitting for me. I had a heck of a day with the bat and we only lost 35-10. I was a switch-hitter from then on, but my natural side, the right side, was my stronger side. I always took batting practice left-handed because I knew that was where I needed the work.”

THREE-SPORT STAR

Green was a three-sport star at El Cerito High School in Richmond. “When the calendar changed, I moved on to whatever sport was in season. And we had some great high school sports teams in the area. I remember playing against Frank Robinson (Hall of Famer), Vada Pinson (former Cincinnati Reds star), and Curt Flood (former St. Louis Cards star) when we were all kids. You could see even then that they were going to be big leaguers.

“They all went to McClymonds High School in Oakland, where Bill Russell played basketball before going on to the University of San Francisco and the Celtics. McClymonds beat us in basketball, but we were better in baseball.”

“My first love was actually basketball. And I think that may have been my best sport. But I was offered a baseball scholarship to Fresno State, so that’s where I was headed after high school.”

Looking back over 50 years, at the time of our 2004 interview, Pumpsie thinks the biggest influence in his baseball career was Gene Corr, who had been his first baseball coach at El Cerito High. “I was all set to go to Fresno State, but Gene Corr had moved up to become the baseball coach at Contra Costa Junior College, and he wanted me to go there. He promised that I could play shortstop if I went there, so I changed my plans and went there. I’m glad I did.”

Pumpsie polished his skills under Corr and after his final season at the junior college, his mentor helped him to advance to the next level. “In my senior year at Contra Costa, Gene Corr got me a tryout with the Oakland Oaks. It was like a dream coming true. I got into his car, and we drove to Oakland, which was seven or eight miles away. I tried out with the team for a week.

“My workout would take place before the regular team did its exercises. Then when the game started, Gene Corr and I would sit in the stands and watch the games. I’d talk to the Oakland third baseman, Spider Jorgensen. My favorite player was Piper Davis, who made it to the majors.”

THE LONG ROAD TO FENWAY

“The people in charge of the Oaks finally came to a decision about me. It was just sign and go play ball. Oakland was an independent team, so there was no draft that applied to me. I got no bonus, just a regular salary of three or four hundred dollars a month.”

Pumpsie Green got his start in professional baseball in 1953 with the Oaks’ farm club at Wenatchee in the state of Washington. “It was an adjustment. I was only nineteen, away from home for the first time. It was a small town, the apple capital of the world,” Green recalls with a chuckle.

“I did okay as a rookie. Then the next year at Wenatchee I hit almost .300 (.297), and scored a lot of runs. I had a good season, stole a bunch of bases.”

His strong second season earned him a promotion to Stockton, the Oaks’ top farm team in the California State League. “I was having a great year, we were in first place, and it was the middle of June. Then one day my manager Roy Partee told me, ‘Hey, Pumps, the Red Sox bought your contract. You are going to their organization, to Montgomery, Alabama.’

“I was excited that a big league club had that kind of interest in me. But I did not want to go. I wasn’t ready for it. They told me that Earl Wilson was there and I could be his roommate, but I don’t think there was a black man in America who wanted to go to Montgomery, Alabama, in 1955.”

Pumpsie was allowed to finish the season in Stockton and he was voted the league’s most valuable player. He joined the Red Sox organization the following spring and spent the 1956 season with the Red Sox farm team in Albany, New York. The following season he was advanced to Oklahoma City in the Texas League, and his fine play earned him a promotion to the Red Sox top minor league team in San Francisco to finish the 1957 season.

“That was a big thrill,” Pumpsie remembers. “Coming back to the Bay Area and playing in the Pacific Coast League after following the teams in that league as a kid. The team was in the pennant race and I hit well (.333), so it’s a nice memory.”

The following year the Red Sox Triple A franchise was moved to Minneapolis and Pumpsie spent that season playing shortstop for the Millers. After a full year at the top minor league level, he was invited to the Red Sox major league spring training camp to prepare for the 1959 season.

HISTORY IN THE MAKING

The 1959 Boston Red Sox spring training camp was the teams’ first in Scottsdale, Arizona, and Pumpsie Green was the focus of the media. In June 1958, Ozzie Virgil had become the first African American to play for the Detroit Tigers, and the Red Sox were on the verge of becoming the last team in the major leagues to integrate.

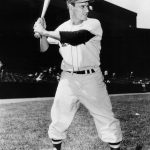

“I didn’t think of myself as another Jackie Robinson, as a pioneer with the Red Sox. I just wanted to make the club. The press wanted to make a big deal out of it, but I just wanted to play. I met all the guys, including Ted Williams, and they were great to me.

“I had the best spring of anyone on the team, including Ted Williams. Everyone told me I was going to make the team, but when we were barnstorming back to Boston, I was sent back to Minneapolis. The writers all wanted to know what I thought, and I said, ‘You are asking the wrong person.’ I just put it in the perspective that there were only so many roster spots and I didn’t have one of them.”

Pumpsie Green went back to Minneapolis and batted .320 during his three months with the team. After scoring 77 runs in 98 games, and excelling at shortstop, he got a telephone call in the early morning hours of July 21, 1959.

“The phone rang at about 7 a.m. and I couldn’t imagine who was calling at that hour. They told me to pack my bags and get to Chicago as quickly as I could to join the Red Sox. Just like that I was on my way to the big leagues.”

Green joined the team in Chicago, and manager Billy Jurges sent him in to pinch run in the eight inning of his first game. He stayed in the game to play shortstop in the ninth inning, but his clearest memory is of starting the next day against future Hall of Fame pitcher Early Wynn.

“I’ll never forget my first at bat. I’m facing Early Wynn, who I had seen pitch on television in the World Series. I had two strikes on me before I knew it. I finally just flicked my bat and grounded out to second base. That was probably my worst at-bat in the major leagues.”

WELCOME TO BOSTON

When the Red Sox returned to Boston for their upcoming homestand, the team was greeted by a large media contingent. “We’re getting off the plane, and all of a sudden all these bright lights came on. I just thought that was what happened every time. It wasn’t until later that I realized the cameras were there because of me.”

Pumpsie did pick out one familiar face in the waiting crowd. “Bill Russell was there waiting to pick me up. I had known him since our high school days and it was nice of him to go the trouble. He drove me to my hotel and wished me luck. He was a big help during my time in Boston.”

Fenway Park was sold out for Pumpsie Green’s debut in a Red Sox uniform. “I guess a lot of people showed up to see me, but the team always drew well.” When it is pointed out that the Red Sox attendance only averaged about 13,000 fans in 1959, the self-effacing Green acknowledges, “Yes, I guess most of them were there to see me. I remember it was so loud you could barely hear. It was a little nerve-racking.”

Shortly after joining the team, Ted Williams approached him and said, “Come on, Pumpsie, let’s go warm up.” The pair warmed up before every game until Williams retired at the end of the 1960 season.

“I had gotten to know Ted in spring training and we got along well. He didn’t say anything beyond the invitation to play catch, and it surprised me a little bit. But I understood and appreciated the gesture. I respected and admired that man.”

One week after Pumpsie joined the team, pitcher Earl Wilson was called up from Minneapolis and became the second African-American to play for the Boston Red Sox. Green chuckles when it is pointed out that he was almost the second African American to play for the team. “Things would have been a little different,” he muses. “But you play with the hand they deal you,” he reflects.

Pumpsie Green and Earl Wilson became roommates and their relationship was still strong in 2004. “I saw Earl at a baseball card show in Sturbridge, Massachusetts, a few months ago. He’s a good man. We spent a lot of time together coming up to the Red Sox through the minors and then in the majors.”

SETTLING IN

The 1960 season was Pumpsie Green’s first full season with the Red Sox and he appeared in 133 games, playing mostly at second base. He was less of a celebrity and more of a regular member of the team in his second season with the club. “I felt a little more comfortable that second year. You know, the baseball was always easy. It was the rest of it that was hard.”

Green remembers many of his teammates with fondness. “Ted was special, and of course Earl and I were close, but there were a lot of good guys on those Red Sox teams. Frank Malzone was a real nice guy. Jackie Jensen was a great athlete and a terrific teammate. I had watched him play football at the University of California, and play for the Oakland Oaks because I was younger than him. It was great to have him as a teammate.

“Pete Runnels was another great guy. I remember him especially as a great teammate. We had a lot of good guys, but those are the ones who come to mind.”

The Bay Area history was helpful to Green in adjusting to Boston. In addition to former basketball rival Bill Russell, Pumpsie connected with another University of San Francisco alumnus, K.C. Jones. “A lot of the Celtics players were a big help getting comfortable with the city. I remember that Bill Russell would have Earl Wilson and I out to his house for dinner at least once a month. It really meant a lot.”

At Spring Training in 1961, it seemed that Pumpsie was poised to move his big league career up to the next level. He played well in pre-season and he was named as the starting shortstop when the team broke camp. On April 21, 1961, he doubled against the White Sox to tie the game, and his home run in the eleventh inning was the game winner, breaking a Red Sox losing streak. But a stomachache in Washington, D.C., in mid-May derailed his career advancement.

“The pain was so bad I called Win Green [Red Sox trainer], and he took me to the hospital. It turned out I had appendicitis and they operated on me. That set me back.”

Green was out of the lineup for about four weeks, and it took him even longer to get his full strength back. But he does vividly remember a rare display of power later that season.

“We were in Anaheim and I hit two home runs in one game and then I hit another homer the following night. I remember it so clearly because one of the Los Angeles writers wrote something like, ‘How can a weak hitter with a funny name like Pumpsie hit all those home runs, when Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris couldn’t do anything like that when the Yankees were here last?’

“That really bothered me. It’s one thing to criticize a player when he makes an error and plays badly, but I didn’t think what he wrote was fair. So I sat down and wrote him a letter to tell him so. I showed it Vic Wertz, who was a good friend, and asked him what he thought. He agreed with me and told me he would deliver it and tell the writer what he thought as well.

“Well, the next day the writer apologized to me in the paper. I remember it so well because I thought he did the right thing and it meant a lot to me.”

WINDING DOWN

By the 1962 season, Green had settled into a key role as a back-up infielder and frequent pinch-hitter. During his Red Sox career he had 22 base hits as a pinch-hitter, the tenth-best total in Red Sox history. But it was his fielding that Pumpsie remembers best.

“I always thought of myself as a better fielder than a hitter. I covered some ground and I had a pretty good arm. When I look back, my favorite memories are of turning a double play, not hitting a home run.”

In December 1962, the Boston Red Sox traded Pumpsie Green to the New York Mets. His career with the Red Sox was over. Today, Green looks back philosophically on his role with the team.

“People will sometimes ask me if I wished I had played for another team. I tell them, no. If I had it to do over, I wouldn’t change a thing. I wanted to be a ballplayer and I was able to do it.

“It was tough there from time to time, but it was rough in lots of places in the United States at that time. I always told people I had enough trouble trying to hit a curveball. I wasn’t going to worry about some loudmouths.”

Green played 16 games at third base for the Mets in 1963. But most of his time during the next three seasons was spent in Buffalo, New York, with the Mets’ top farm club. “It was tough adjusting to life back in the minors, but it was still professional ball. And I was playing with and against some good players. All I had ever wanted to be was a professional ballplayer.”

Hobbled by injuries, Green decided to call it quits after the 1965 season. “My hip was really bothering me. It was time. I had spent 13 years playing the game I loved at the professional level.”

BACK HOME IN THE BAY AREA

After he retired from baseball, Pumpsie went to work at Berkeley High School in Berkeley, California. “I was at Berkeley High until I retired after more than 30 years there. I was a counselor and I coached baseball for over 20 years. I even taught math in summer school. In a school system like that you do a little bit of everything.

“We had some good ballplayers come out of Berkeley. Claudell Washington (seventeen year major leaguer) played there. Rupert Jones played at Berkeley. We had some good players and a lot of good kids.”

Pumpsie followed the football career of his younger brother Cornell closely. “He went to Utah State on a basketball scholarship. I remember he came to see me in Arizona during spring training one year. He was trying to decide whether to play pro basketball with the Chicago Bulls or football with the Dallas Cowboys. He wanted my advice.

“I asked him what he really wanted to do. He told me he was leaning towards football. I said, ‘Then give it a try. If it doesn’t work out, you can always go back to basketball.’ It worked out pretty well for him,” Green says of the five-time Pro-Bowl defensive back.

“My brother Credell played for the Green Bay Packers for a year. And my brothers Travis and Eddie Joe were good athletes, too. Somebody was always playing ball in our house.”

Pumpsie and his wife Marie bought their present home in El Cerrito, California, seven years after his retirement from baseball. The Greens celebrate their forty-seventh wedding anniversary this year.

On the day of his 2004 interview, Pumpsie Green was getting ready to attend his daughter Heidi Keisha Green’s graduation. “She’s getting her Masters Degree from Mills College tomorrow. We’re very proud of her. She’s so busy it’s hard to keep track of her.”

Pumpsie was equally proud of his son Jerry who lives in Castro Valley, California. But the clear apple of his eye was Jerry’s 14-year-old daughter Brittany. “I try to see her as often as I can. She’s very special to us.”

Asked if he is a Red Sox fan today, Pumpsie responds emphatically. “Of course I am. They’re my team. I want them to beat Steinbrenner’s guys and win the whole thing. Let’s put it this way, whenever I wear a ball cap, and that’s a lot of the time, I wear a Red Sox cap!”

Like 99.9% of the athletes who play major league baseball, Pumpsie Green is not headed to the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York. But if they establish a Good Guys Hall of Fame, he would be a charter member. Pumpsie Green is much more than just an important footnote in the history of the Boston Red Sox.

His last visit to the Red Sox was in April 2012, when he attended the Fenway Park’s 100th anniversary celebrations. Two days later, he threw out the ceremonial first pitch before the Red Sox game on Jackie Robinson Day.

Pumpsie Green died at San Leandro (California) Hospital on July 17, 2019, at the age of 85. He was survived by his wife of 62 years, Marie, their daughter Heidi, three brothers, and several grandchildren, nieces, nephews. He was preceded in death by his son, Jerry, who passed away in February 2018.

Clearly, Pumpsie Green was a lot more than just a footnote to the history of the Red Sox. He is an important part of the legacy of this iconic franchise.

-END-

Leave A Comment