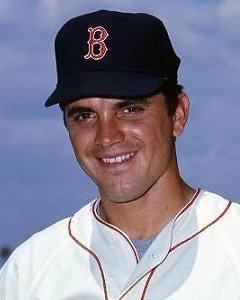

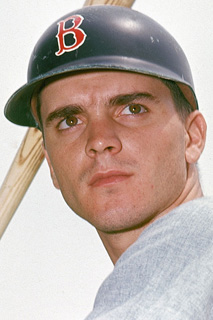

In June of 1962, Tony Conigliaro of Swampscott, MA, was a star outfielder for St. Mary’s High School of Lynn. By April of 1964, the 19-year-old Conigliaro was a starting outfielder for the Boston Red Sox.

In his first at-bat at Fenway Park, Tony Conigliaro hit the first pitch thrown to him for a home run. In his rookie year he belted 24 roundtrippers to set a major league record for home runs by a teenager. In 1965 he hit 32 homers to lead the American League, making him the youngest player to ever lead the league in home runs. In June of 1967 he hit his 100th major league home run. At age 22 years, 6 months and 16 days, he was the youngest player in the history of the American League to reach that level.

But Tony Conigliaro was more than a home run hitter and more than raw statistics. Tony C. was a local hero. He was one of us.

JOHNNY PESKY REMEMBERS

Red Sox favorite Johnny Pesky, who joined the big league ball club in 1942, was the team’s manager when Tony C. reported for spring training in 1964. Pesky always remembered the first time he saw Tony hit.

“I thought he was the best young hitter I had seen in a long time. He reminded me a bit of Ted Williams when Ted was a teenager. They were both tall and lean” Johnny recalled. “And you could see right away that Tony worked as hard on his hitting as Ted used to.

“He had played only a short season in the minors but you knew right away that he was going to be a good one. Of course his parents, Sal and Teresa, lived around the corner from our home in Swampscott [MA], so I knew I was getting a good kid.”

When Ted Williams was a teenager playing in the Pacific Coast League, legendary hitter Lefty O’Doul, who had lifetime major league batting average of .349, watched the young phenom taking batting practice. O’Doul told Williams, “Whatever you do kid, don’t let anyone change that swing.” After Williams watched Conigliaro hit in spring training in 1964, Ted’s only advice to Tony was, “Don’t change a thing.”

Although the 19-year-old Conigliaro was a long shot to make the big league club, Pesky gave him plenty of playing time. Tony made the most of his opportunity, playing well in the outfield and hitting big league pitching with power.

“I remember one home run he hit,” Pesky reminisced. “It cleared a fence in centerfield that was probably 450 feet from home plate. One of the writers went out to measure it and figured it had traveled about 530 feet.

“But I had to fight to bring him to Boston with the big league club. They wanted to send him to the minors for more seasoning, but I wanted him in my outfield.”

When the writers asked Pesky if Tony had made the team he responded, “Do you want me to be shot by the fans back home? Yes, Tony will be in there.”

HOME TOWN BOY MAKES GOOD

To get to Fenway Park from Tony Conigliaro’s birthplace of Revere, MA, you take the MBTA’s Blue Line to Government Center in downtown Boston and then change for the Green Line. But Tony’s journey to Fenway involved thousands of hours on the baseball fields of Boston’s North Shore.

Tony often recalled his early days on the baseball diamond near his home in East Boston. “I’d get up every day, put on my sneakers, asked my mother to tie the laces for me, and run out the door to the ball field across the street from my house. That’s all I wanted to do. I was there so much that the other mothers in the neighborhood began saying my mother wasn’t a very good one because she let me stay out there all that time.”

Tony’s younger brother Billy spent three seasons with the Boston Red Sox, two of them playing in the same outfield with his big brother. “I don’t know if people realize how hard Tony worked to get to the big leagues and how hard he worked to stay there. He would spend hours swinging a lead bat or squeezing a ball.”

Richie Conigliaro is the youngest of the three brothers. “I remember pitching to Tony in the parking lot of Suffolk Downs Race Track. When we moved to East Boston from Revere our house was right above the track. Tony hit a line drive back at me and it caught me right in the forehead. I went down for the count!”

The local legend of Tony C. began in the East Boston Little League where he excelled. Tony always singled out his coach Ben Campbell for praise. “Every kid in the world should have a little league coach like Mr. Campbell,” Tony insisted. “I think that the course that I followed all through baseball was started right there under Mr. Campbell.”

Tony’s excellence on the baseball diamond continued as he moved from Little League to Pony League ball. “Tony stood out at every level,” his brother Billy remembered.

THREE-SPORT STAR

Tony was a three-sport star at St. Mary’s High School in Lynn. Tony and his father Sal drove from their Swampscott, MA, home to school every day. Sal would finish work at the nearby Triangle Tool and Dye Company and pick Tony up from practice for whatever sport was in season.

Baseball scouts first took notice of Tony in his sophomore year. They had turned out in droves to scout pitcher Danny Murphy of St. John’s Prep in Danvers, who eventually signed with the Chicago Cubs for a six-figure bonus. Murphy only gave up four hits to St. Mary’s of Lynn that day and three of them were to Tony Conigliaro.

In addition to his baseball prowess, Tony excelled at basketball and football. On the basketball court he set the St. Mary’s school’s scoring record with 417 points in his senior year. And on Thanksgiving he led the football team to victory over their larger Lynn public high school rival.

In his junior and senior years at St. Mary’s Tony hit over .600 and pitched his team to 16 victories. Following his graduation from St. Mary’s of Lynn, Tony played in the Hearst All-Star game in New York City, tracing the footsteps of such Red Sox luminaries as Harry Agganis, and his future teammates Billy Monbouquette and Gary Bell. After his American Legion baseball season ended in September 1962, Tony signed with the Red Sox for a bonus of $20,000.

His first stop was Bradenton, Florida, for winter ball. At Bradenton Tony learned how hard he was going to have to work to make it to the major leagues. He also established a lasting friendship with catcher Mike Ryan of Haverhill, Massachusetts. Conigliaro and Ryan both made it to the Red Sox in 1964 and continued as teammates through the Impossible Dream season of 1967.

Tony spent the 1963 season in Wellsville, New York, playing for the Red Sox farm club in the New York-Penn League. Future Red Sox teammates in Wellsville included George Scott and Joe Foy. His .363 batting average and 24 home runs earned him an invitation to the Red Sox spring training camp in Scottsdale, Arizona, in 1964.

NEXT STOP KENMORE SQUARE

The hometown boy was an overnight sensation with the 1964 Red Sox. By midseason he was averaging 100 fan letters per day, most of them from teen-age girls. He finished the season with a .290 batting average to go with his 24 home runs. If he hadn’t had his arm broken by an errant pitch late in the season his offensive totals would have been even more impressive.

If Tony was concerned about a “sophomore slump” in his second season, his numbers didn’t show it. His 32 home runs led the American League and he drove in 82 runs.

Tony made an impromptu appearance at brother Billy’s 1965 high school graduation from Swampscott High School. Tony took the microphone after a brief introduction from the Principal and informed the crowd; “My brother Billy has just been selected first by the Boston Red Sox in the first major league draft.”

By the 1966 season, Tony C was an established big leaguer. The Red Sox finished a distant ninth in the standings that year, but Tony rapped out 28 home runs and upped his RBI total to 93.

Long-time Red Sox broadcaster Ken Coleman had an interesting perspective on Tony C’s status as a hometown hero. “In addition to broadcasting in Boston, I worked in Cleveland and Cincinnati over the years. Most of the hometown players I saw had some trouble with that role. It seemed to make it tougher for them. But not Tony. He actually seemed to relish his role as the hometown hero.”

THE IMPOSSIBLE DREAM SEASON

Tony C and his brother reported together to spring training in 1967. They made it a point to report early.

“Tony ran me into exhaustion during our three weeks together. He had more to do with my eventually making it to the big leagues than any other person.”

The 1967 season started slowly for Tony. First he was injured by a John Wyatt fastball in batting practice during spring training. Then a bad back bothered him. At the end of May he was batting .304 but he had only contributed two home runs.

His home run drought didn’t worry his teammates. Teammate Russ Gibson recalled, “Tony had a beautiful home run swing. You would see him lift one over the leftfield wall at Fenway and you’d think, ‘What a great Fenway swing this guy has.’ Then we would go to someplace like Kansas City with a deep outfield and he would drive one 420 feet just over the fence. He had a knack for hitting them just far enough for a home run.”

By mid-June the Red Sox had established themselves as pennant contenders and Tony C was on a tear at the plate. Like many fans, Richie Conigliaro recalls the Red Sox game on June 15th as one of the season’s turning points.

“I was 14 that year and I got to a lot of games. I used to ride in with Tony all the time. Of course I was scared to death when we got there because he drove like a madman. I remember that game against the White Sox because it was almost like a playoff game.

“It was 0-0 after ten innings and then the White Sox scored a run in the top of the eleventh. Joe Foy got on and then Tony hit a home run to win it 2-1. I remember the crowd went crazy and his teammates mobbed him at home plate.”

Tony’s dramatic home run had helped to coin a memorable phase. The following day a Boston Globe headline writer used the phrase “Impossible Dream” to describe the 1967 team’s exploits to date. And almost 50 years later it is still the catch-phrase of the 1967 Boston Red Sox.

As June came to an end, Tony’s home run total for that month stood at nine. To cap it off, he was named to the American League All-Star team. There was every reason to believe that 1967 could be his greatest season yet.

On July 23rd Tony hit his 100th career home run in the ninth game of a ten-game Red Sox winning streak. At the time he was believed to be the youngest player in major league history to reach this milestone. Later it was discovered that New York Giants Hall of Famer Mel Ott had topped Tony’s record by a matter of days. When you consider that Ott had already played 117 major league games before he turned age 19, Tony’s age in his rookie year, Conigliaro’s achievement is even more remarkable.

As the temperatures of July and August rose, Tony’s bat got even hotter. He totaled 8 home runs and 18 RBI for July. By mid-August he was up to 20 home runs and 67 RBI.

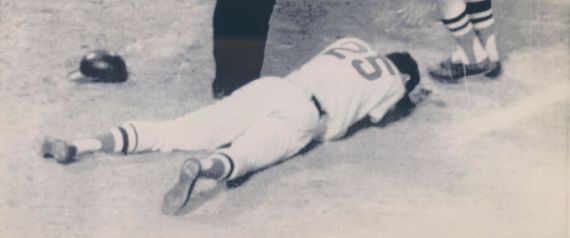

On August 18, 1967, Tony spoke with his business manager Ed Penney who told him, “I saw Ted Williams recently and he told me to tell you to stop crowding the plate. He said you should get back before one of those guys hits you.”

That evening, pitcher Jack Hamilton of the California Angels hit Tony C. on the left side of his head with a fastball that sent Tony writhing on the ground with pain. Tony’s teammates rushed to his side. His family joined a bedside vigil at Sancta Maria Hospital that evening. Tony C’s 1967 season was over.

AUG 23 1992; Special to the Denver post, Attn: Jerry Cleveland — This is and Aug. 19. 1967 file photo of Boston Red Sox outfielder Tony Conigliaro, on the ground after being beaned by California A’s Pitcher Jack Hamilton at Fenway Park in Boston. Red Sox Rico Petrocelli is coming to his aid. 1987 (Photo By The Denver Post via Getty Images)

The Red Sox received permission from the Commissioner’s Office to allow Tony to sit on the Red Sox bench for the season’s final game. Tony did his best to celebrate with his teammates as the team clinched its first American League pennant in 21 years. Finally, overcome by depression, Tony put his head in his hands and cried in front of his locker.

Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey spoke for all Red Sox fans when he put his arm around Tony and said, “Tony, you helped. Those games you won for us in the early part of the season, well, they’re just as important as today’s game.”

It is essential for Red Sox fans of all ages to remember that without Tony C, the Impossible Dream season would never have been possible.

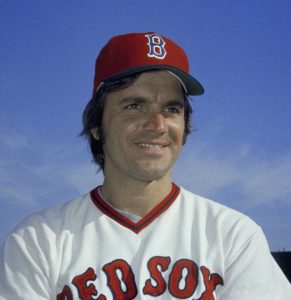

COMEBACK PLAYER OF THE YEAR

Tony Conigliaro attempted a comeback at spring training in 1968 but he simply could not see well enough to hit at the major league level. While trying his hand at pitching in the fall Instructional League that year, a few solid hits encouraged him to try again in 1969.

On opening day in Baltimore in 1969, Tony hit a tenth inning home run and scored the winning run in a 12-inning victory over the Orioles. On Opening Day at Fenway Park one week later, the fans gave Tony C a series of ovations that rocked the ballpark to its foundations.

In one of the great comebacks in sports history, Tony drove in 82 runs in 1969 and hit 20 home runs. He was voted the Comeback Player of the Year, and he received the Hutch Award for being the player, “who best exemplified the fighting spirit and burning desire of the late pitcher and manager Fred Hutchinson.”

It is often written that Tony Conigliaro was never the same player after his tragic beaning. That is simply not true. His eyesight was never the same again, but 1970 was his finest offensive season.

“When we would throw the ball to one another,” Billy Conigliaro remembers, “if he closed his right eye he wouldn’t be able to catch my return throw. And he used his peripheral vision to hit the ball.”

In 1970 Tony C set career highs in home runs, runs scored, and RBI. His 116 RBI placed him second in the American League, and his 36 home runs ranked him fourth. The brothers Conigliaro combined for 54 home runs, establishing a new major league record for brothers playing on the same team.

That fall the unimaginable happened: the Red Sox traded Tony C to the California Angels. For diehard Red Sox fans it was like trading the USS Constitution to Baltimore for the USS Constellation.

Tony C never adjusted to life as a California Angel. He retired in mid-season with a batting average of .222. “I think being traded 3,000 miles away broke his spirit,” Richie Conigliaro speculated. “It just wasn’t the same thing as playing his home games in front of friends and neighbors.”

Tony had been out of baseball for three-and-one-half seasons when he phoned Red Sox General Manager Dick O’Connell to ask if he could try another comeback at the 1975 spring training camp. O’Connell told him that he was welcome if he would pay his own way.

Defying all odds, Tony hit the cover off the ball in spring training. When the Red Sox opened at Fenway Park that season, Tony was the designated hitter. He singled in his first at bat and the crowd gave him a three-minute standing ovation. But hamstring and groin injuries hampered his comeback, and he retired from baseball for the last time in August 1975.

After baseball, Tony enjoyed a successful career as a television broadcaster in San Francisco. In January 1982 he interviewed for the color job on Red Sox telecasts. Tony suffered a heart attack while Billy Conigliaro was driving him to the airport for a return trip to the West Coast.

Tony never recovered from this episode, and he died on February 24, 1990, a little over a month following his forty-fifth birthday. Nearly 1,000 people gathered at St. Anthony’s Church in Revere to mourn his passing.

WE ARE FAMILY

“When people think about his career, I hope that people will remember that family was always first for Tony. Baseball was very, very important to him, but family was always most important. He came home to visit and to eat our mother’s cooking every chance he got,” Richie Conigliaro remembered in our l0ng, emotional interview a few years ago.

“That’s true of all of us,” Billy added. “If something great happened to one of us, Tony included, the first thing we would do is call home to tell the family about it. We have always been a very close-knit family.”

The Conigliaro’s have learned over time that fame has its’ price. But they deal with it with humor rather than rancor. Billy recalled what it was like as a schoolboy when your big brother plays for the Boston Red Sox. “When I would strike out some fan was sure to yell, ‘Hey Conigliaro, you’re a bum, just like you’re brother Tony!’”

“You think you had it tough?” Richie laughed. “There I am trying to play high school baseball, and I’ve got one brother starting in right field for the Red Sox and the other brother starting in center field. When I would strike out they would yell, “Hey Conigliaro, you’re a bum, just like your brother Tony and your brother Billy!’”

The Conigliaro brothers treasure their brother’s memory, and enjoy reminiscing about his human qualities. Asked if either of them have their brother’s fine singing ability, they both rolled their eyes. “He was a ham,” Richie added.

Tony’s appeal to the ladies is also fair game. “Remember Mamie Van Doren?” Richie asked. “How could I forget,” Billy responded in reference to Tony’s well-publicized romance with the Hollywood starlet.

“I remember one time when we were both on the team,” Billy continued, “when I spotted a very attractive young lady sitting behind the Red Sox dugout. I asked the batboy to have someone bring her a note to meet me after the game. A little while later he came back with a baseball. I figured this is great; she wants me to autograph the ball. Then I notice some writing on the ball. I read it and it says, ‘Meet me after the game: Tony Conigliaro.’ My brother had spotted her before me!”

WHAT MIGHT HAVE BEEN

When his former teammate Dalton Jones is asked what Tony might have accomplished if he remained healthy for a full career, Dalton answers with a straight face, “He would have hit over 800 home runs before he retired, he would have gone to Hollywood and become a movie star, and then he would have come back to Massachusetts and been elected Governor. And I’m only half-kidding,” he added with a smile.

Baseball researchers have built a computer model that allows you to match players’ performances with the statistics of every player who has ever played the game. When you enter Tony’s batting statistics, his closest match at ages 20 and 21 is former Yankee great, Hall of Famer Mickey Mantle. For his abbreviated 1967 season at age 22, his match is Hall of Famer, and former big league manager, Frank Robinson.

Tony Conigliaro

There is near unanimous agreement that if Tony had been able to play a full career in good health then he would have been a shoo-in for baseball’s Hall of Fame. Johnny Pesky said, “I would bet my house on it!” His uniform number “25” would now be displayed on the façade in Fenway’s right field along with the numbers of the other Hall of Famers who played ten or more seasons with the Red Sox and finished their career with the club. But in fact, Tony’s number “25” was retired in the hearts and minds of Red Sox fans a long, long time ago.

It is hard to believe that Tony C has been gone for over 25 years now. But for as long as New England kids play baseball in March with snow shoveled to the sidelines, and dream of someday starring for the Boston Red Sox, the spirit of Tony C will always be among us.

Red Sox should retire #25 ! A true superstar in the making…….and a very good right fielder as well !

You are exactly right!

I met Tony C back in 1965 and then again in Spring Training in 1968. He was truly a wonderful person and I am glad I have him on Super 8 video to always remember him as the Great Ball Player he was and the pain he endured to play. Once coming to a after game loss on a Sunday to our Fan Club President’s House he was so tall he barely cleared the ceiling. He was driving his 65 Grey Corvette and he let me follow him up 24 where I had to exit to Fall River as he went home to Boston. But he waved and didn’t try to overtake my 66 Mustang which use to putt putt. I had told my friends how many big leaguers would do that? He let me keep pace with him and then waved as I exited 24 to go home. Those photos and memories will live forever in my heart and mind. Rest In Peace TC, we loved you!!!!!!!!! MTLL

Great story….I knew Tony for years and have read just about everything ever written about him. Still can’t figure out why there’s never been a movie made of his life, just high lighting the good, exciting things. Too few people know what a great kid he was and how much he did for so many people…not to mention how he lifted the hearts and spirits of an entire community. For all he meant to the Red Sox it’s still unspeakable that his number has never been retired. Rest in piece “Kiddo.”

Great story. I watched Tony play for Wellsville in the NY-Penn League when I was in high school. Tragic story of a phenomenal ball player.

Great story Wily!

My former husband was in the band at Odee’s Nightclub in Cambridge MA and Tony would sing there. He was a ham, and many thought that his singing was not that great..but he was a lovely person and always gracious to anyone that asked for his time.

Flash forward many years and we are now living in San Francisco where Tony was with a local station as a sports broadcaster..he walked into a local place that I happened to be in and he immediately recognized me and came over to say hello….his good old Boston area accent still in full sound….what a lovely man and it’s so sad that he did not have longer in this world.

Great stories!

Tony see is buried right near my Mother and Father at holy cross cemetery- every time I go I try to leave some flowers or something for Tony. I often stop and just say a prayer.

Sorry meant to type Tony C. As a teenager I often went to his restaurant in Nahant.

That’s nice, Barbara.

Tony C was my idol, in 1968 we had identcal speed boats in East Boston, God only knows how great he could have been.

My personal hero was Carl Yastrzemski but my favorite baseball picture is one that my father tok in the Red Sox clubhouse on July 13, 1967 with Tony C on my right and Yaz on my left. Yaz was always my #1 but Tony was my #1 1/2…

thank god someone wrote about this great ball player that never finished his due,larry taylor a fan

Tony Conigliaro will never be forgotten as long as there are Red Sox fans. I agree that his number should have been retired long ago ! He certainly earned that honor with his bat and glove not to mention almost dying at home plate on that awful night!

Well said my dear!!

Tony was great to us when we played his nightclub Tony C,s

I’m Mick Spiros and I was the lead man for ITMB. We played there a lot. Tony would come up and sing a song or two with us. I remember meeting his Brothers and having fun outside the club scene. He was great and fun to be with. Will be missed forever.

Mick

Michael Spiros from the Incredible Two Man Band….ITMB

Was a pleasure to play for Tony’s Club and privilege to have been his friend

I was at an event about 2 years ago.The Farley Brothers were suppose to be there also although I never saw them.There was talk of them doing an autobiography on Tony Coningliaro.I never heard any more about it and truly wish one would be done as I had such a HUGE crush on him and will never forget him as a Red Sox fan that I am proud to be.Thanks for posting this story.

I met Tony at The Sportsman and camping show in Boston at The Hynes center he signed my book for me. I was on cloud 9 for weeks. My girlfriend and I used to go to Red Sox games in August and it was Bill Conigliaro’s birthday and we would bring him a cake and sometimes Tony would come out to say hello to us. After his heart attack there was a benefit concert at Symphony hall with Frank Sinatra and Dionne Warrick my mom her friend and I went. They had a Tony C night at Fenway we also attended that. Red Sox organization PLEASE retire #25!

He was my hero great ball player

I used to copy everything he did have his 45 record was my Italian style

His Uncle Vinnie would setup hitting practice in Revere for Tony to work out. When we saw Tony hit we knew he was a very special ball player.

So we all when back to school knowing we better get an education.

His uncle Vinnie Martelli had a big part in the baseball success of Tony C.