The first time I met Ted Williams, he was as Splendid a Splinter as the legend suggested.

The first time I met Ted Williams, he was as Splendid a Splinter as the legend suggested.

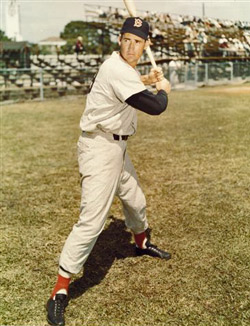

It was the summer of 1956, four years before he’d retire as an active player, and I, not yet into my teens, was ready with an autograph book. The tall, handsome man approached jauntily, wearing a powder blue, v-neck sweater over a shirt open at the collar, and chino slacks.

It was at the back of the Somerset, the Boston hotel where Ted lived during the baseball season. The Red Sox slugger was walking to the garage to pick up his car for the short drive to Fenway Park.

I intercepted him, pen and autograph book outstretched. “Can I please have your autograph?” Without a word, Ted took the book, held it low against his right thigh and penned his distinctive signature. I thanked him and he was off to his car and another day at the ballpark.

I was off on Cloud Nine. Number Nine, the baseball hero of my boyhood, had signed my autograph book.

Now that I had him once, I hungered for more. There was no lack of objects to have him sign: baseballs, photos, other autograph books. You name it, I wanted it signed.

One day, after several such wordless, but successful, encounters at the back of the Somerset, Ted was walking with a friend, headed for the garage. Ted saw me waiting, pen and baseball in hand. As he approached, he admonished, “This is the hundredth goddamn time. When is this gonna stop?”

He wasn’t angry, though. He reached out to me, shaking his head in mock disgust, and smiled. He took the pen, signed the ball and moved toward his car. No matter what he ever said, he never refused to sign. As a kid, I got The Kid’s autograph on one thing or another 17 times.

On another occasion, at the players’ parking lot at Fenway Park, I was there with an autograph book as Ted got out of his car and made his way toward the player entrance. I extended my book through the fence and, spying the longtime security guard, Tim Lynch, Ted bellowed: ‘‘See this kid? He’s here every day.”

No matter. Ted signed. No problem.

It was easy to adore Theodore Samuel Williams if you were a Boston boy growing up in the 1950s. He was electric. The good looks, the loping stride, the home runs, oh, those long, high-arc home runs – majestic clouts nearly all of them. If you

Were listening to a Curt Gowdy broadcast of one of Ted’s 521 round trippers, you were likely to hear, “There’s a high drive to deep right field … that ball is … going … going … gone … a home run.”

Many Red Sox fans in the 1950s wouldn’t wait for the final out before leaving the park, unless Williams was due up. They’d stay until the seventh or eighth inning, awaiting Ted’s last at-bat of the game. Then they’d stream out of Fenway, leaving nothing but an echo in the wind for the final inning or two. The Sox did not field great teams in the late ’50s, and late-inning comebacks were neither anticipated nor frequent. It was safe to leave after Ted’s at-bat.

Of course, I’d stay till the bitter end. There were autographs to gather in the parking lot afterwards.

Ted’s nasty, epic spats with the “knights of the keyboard” – as he had dubbed sports writers – had faded into Boston newspaper lore by the time I joined the knights. Excluding his four-year stint as manager of the Washington Senators/Texas Rangers franchise, Ted’s visits to town were infrequent, generally limited to Jimmy Fund activities and, later, to old-timers games and other events ceremonial. He had mellowed and accommodated the media more graciously. Even to sports writers, Ted’s visits created a buzz. His magnetism was transferable: Of my generation, if you liked him as a kid, you liked him when you were grown. No other sports figure created such a mystique among the supposed hardened journalists. He was still electric, still created a buzz whenever he was around. It was not unusual for writers to ask Ted for autographs.

I recall vividly one interview among several I conducted with Ted. It was on Sept. 26, 1971, when he was in his third and final season as manager of the lowly Washington Senators. He was playful, winking, congenial. In mid-interview, I mentioned the Somerset and the autographs. He stopped, looked at me from behind the desk in the visitors clubhouse, studied my face with narrowed eyes and said, “Was that you?’’ He remembered.

There was speculation that Ted might not manage when the Senators moved to Dallas-Fort Worth in 1972 to become the Texas Rangers. Ted was playfully evasive when I asked him if he would manage the Texas team, particularly in light of a story reporting that then-Dallas resident Mickey Mantle wanted to manage the franchise. “I’m liable to be greeted at the airport in Dallas with signs, ‘MANTLE,’ or ‘BRING BACK STENGEL,’ ” Ted joshed. “That’s got to leave an impression on you, doesn’t it?”

For the record, Ted did manage in Texas, for one year (1972). Mantle never did. Neither did Stengel.

After the interview, a man and his young son – the boy was maybe 4 or 5, and most assuredly didn’t know who Ted Williams was – were outside the clubhouse, in the darkened passageway under the third-base grandstand. “Ted, would you take a picture with my boy?” the man asked.

Without hesitation, Ted obliged. Up the runway and into the park they went, together. Ted scanned the seating area, searching for the perfect spot from which to be photographed. He took hold of the boy, carried him up into a row of seats and crouched down, holding the boy close to him. “Smile at your daddy now,” Ted coaxed the boy as both peered into the camera, Ted with a broad smile, his head cocked toward the little guy who most assuredly still didn’t know who Ted Williams was.

That little boy would be a man now, and most assuredly knows who Ted Williams was.

Dick Trust covered sports for The Patriot Ledger of Quincy, Mass., for 40-plus years before retiring in 2006. Now a freelance writer and photographer, Dick lives in Scituate, Mass. His limited-edition, coffee-table book of never-before-published photos, Ted Williams: Newly Exposed, is available by contacting . Each copy of the book is $49.95 plus shipping. Dick will sign each book upon request.

Great article. Oh to be young again and enjoy Ted Williams

Fine article on Ted. I can still remember the 1946 season. Ted disappointed us in the Series, but he and Bobby Doerr continued to be my favorites.

D. O. D

Great article!!

I had the same experiences in the Somerset Hotel parking lot during 1956 & 1957!

The only difference was, when I asked Ted to sign something, he said ” I’m going to sign this but I don’t ever want to see you here again”. “Do you understand”?

I went back four times during that period.

I treasure those experiences!

Tom Marchitelli

This is a touching article about a great champion and a true fan. Well done.