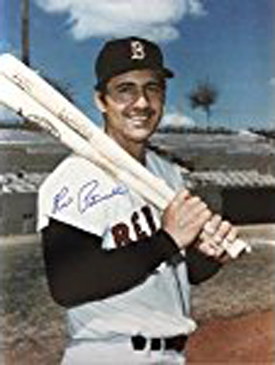

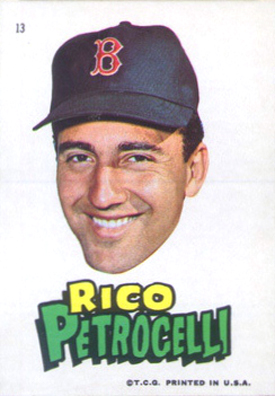

Rico Petrocelli, a Yankee fan as a youngster growing up in the Sheepshead Bay section of Brooklyn, was the anchor of the Red Sox infield when the Red Sox moved into Chicago for a crucial series against the White Sox. There was a certain irony in Rico’s de facto position as the Red Sox “captain” of the infield. In 1966, Manager Billy Herman had fined him $1,000 for leaving a game without permission and at that time Rico had developed a reputation as a sensitive sort for a ballplayer. But baseball was extremely important to Rico and he had matured rapidly. He had long been singled out as the Red Sox shortstop of the future, but on finally gaining the position, he had suffered with the Red Sox through 190 losses in his first two seasons, 1965-66. When Williams came to Rico on March 1, 1967, and told him that he was looking to him for leadership, it was the vote of confidence he needed. Rico felt that he had been empowered to pass on his baseball knowledge to the others, and more importantly, he felt accepted as a big leaguer for the first time. As the Red Sox got ready for the third game of the five game series, they were in a flatfooted tie for second with the White Sox, one-half game behind the league-leading Twins. Rico knew that his teammates were counting on him and it was leadership that he would provide.

Red Sox vs. Chicago White Sox, Saturday, August 26, 1967

The scene was set for a classic late-August pivotal series as the Red Sox flew to Chicago for a five-game showdown starting Friday night August 25, with manager Eddie Stanky and his White Sox. There was no love lost between the Red Sox and Stanky. Eddie had referred to Yaz as “an all-star from the neck down” earlier in the season. While everyone realized that he was just playing head games, they still wanted to beat the diminutive manager who was known as “The Brat.”

The pennant race in the American League was as tight as it had been in years; no one could open up a lead of any significance. The Sox, Red and White, were in a virtual tie for first place. The Minnesota Twins and Detroit Tigers were hanging within a game of the two leaders. The season had only a little over a month to go and the contenders were running out of room to maneuver. The leaders only had about thirty-five games remaining to make their move. For Rico Petrocelli, 1967 was the year he finally felt like a legitimate major leaguer.

Even though he was in his third big league season, he was just starting to feel like he belonged. Baseball had been the most important thing in his life for as long as he could remember but he still had to battle insecurity. Rico was the youngest of five brothers from a close-knit Italian family in Brooklyn, New York. His brothers were all fine ballplayers and big fans, but a job to provide some income for the family was a higher priority. It wasn’t until Rico came along, that a Petrocelli could afford the luxury of concentrating on baseball.

“When I was real young we were all Dodger fans, living in Brooklyn. But when the Dodgers moved to Los Angeles we became Yankee fans. We were all big Yankee fans but I got to see a lot of the Red Sox because one of my brothers loved to watch Ted [Williams] hit.”

Rico was an outstanding young ballplayer on the Brooklyn sandlots and his brothers tutored him and cheered at his games. Throughout his career, they fulfilled their missed opportunities through his exploits. The bird-dogs first took note of his potential as a fifteen-year old performing for the Cadets at nearby Prospect Park. He continued to improve and earned the tag line “can’t miss.” As high school graduation loomed closer, veteran Red Sox scout, Bots Nekola, who had also signed Carl Yastrzemski, took over the pursuit of the young phenom personally.

Petrocelli was an All-Scholastic baseball and basketball player at Sheepshead Bay High School, and he was outfielder and pitcher for his team. At one point there were at least twelve big league teams scouting Rico and following him from game-to-game. But Rico injured his right elbow while pitching in the City Championship game and most of the scouts disappeared. Nekola stuck with his injured prospect and he arranged for Rico to have a tryout at Fenway Park. Rico made the trip to Boston with his mother, father and one of his brothers.

Fast Track Through the Minors

Rico Petrocelli signed with the Red Sox before his eighteenth birthday. Rico’s first stop was Winston-Salem, North Carolina, in the Carolina league. It was a long way from Sheepshead Bay in Brooklyn. Rico recalls, “I was a city kid and I was used to a fast pace. I couldn’t believe how slowly people moved down there. It was there that I saw my first cow. I remember going over to touch it like it was some kind of prehistoric animal like a dinosaur or something!”

The Red Sox had moved Rico to shortstop and he struggled to learn his new position. It was also his first taste of professional pitching and it caught him a little off guard. “When you’re playing sandlot, you hit .400 something, but all of a sudden you’re struggling to hit .280. It was a real adjustment. Sometimes it was discouraging.”

Rico moved up the ladder to Reading, Pennsylvania, in the fast Eastern league. Rico continued to improve as a hitter as he moved through the Red Sox system. There never was any doubt about his fielding. When the Reading regular season came to an end in 1963, the twenty-year-old Rico was brought up to “the Bigs” to spend the last two weeks of the season with the major league club. For a minor leaguer, this was as close to becoming “anointed” as you could get.

Rico started the 1964 season with great optimism. At training camp in Scottsdale, Arizona, he felt that he was being singled out as a prospect. For the first time, he really believed he belonged with the Red Sox. Red Sox manager Johnny Pesky understood shortstops and that helped. Rico was only twenty-years-old but he was assigned to the Red Sox top farm team in Seattle, Washington. He was in Triple-A ball, the last stop before the majors. He was in good company at Seattle. Jim Lonborg was honing his pitching craft and Russ Gibson was demonstrating to the brass on Jersey Street that he was ready for “The Show.”

Things got off to a good start for Rico in Seattle but then he pulled a hamstring and his batting average began to fall. Rico kept playing hurt, afraid he would lose his big opportunity if he sat down, and his average continued to deteriorate. Billy Gardner recognized the syndrome and told him to go to manager Edo Vanni and ask for some time to heal before he put his career in jeopardy.

Rico went to Vanni and explained the situation as best he could. Edo told him that he didn’t want to hear about it and implied in baseball terms that Rico was “jaking it” i.e. malingering. Where Rico grew up, that was akin to questioning your manhood. In the tradition of his Brooklyn neighborhood, Rico responded by questioning Vanni’s parentage. Things deteriorated from there.

In spite of a dreadful ‘64 season, shortstop had his name on it at Fenway Park. He played ninety-three games at the position in 1965, but the grand experiment of Rico as a switch hitter was abandoned early in the season. He still remembers his few left-handed appearances in 1965. “I hit a sharp line-drive down the right field line in Fenway and it was just foul—that was the closest I came to a left-handed base hit in the majors,” he laughed. As a rookie, he banged out thirteen home runs in only 323 at bats and it didn’t make sense to have a guy with that power slapping 125-foot line drives from the left side. Asked when he first felt like a genuine big leaguer, Rico replied, “Not in 1965, that’s for sure!”

The following year, Rico was installed as the regular shortstop right from Opening Day. While he batted only .238, he increased his home run output to 18 and he fielded his position brilliantly. But his relationship with Red Sox manager Billy Herman left something to be desired. The players respected Herman’s baseball knowledge but he was not a great communicator or motivator. By his own admission the 23-year-old Petrocelli was still coming of age and he and Herman had their differences. It all came to a head when Rico was fined $1,000—one-sixth of his $6,000 salary— by the Red Sox for leaving a game early in 1966.

Rico remembered that the 1966 season was very different from 1965, even though the club finished in ninth place once again. “The year started out about the same.” Rico remembered, “And at the half-way point we were in 10th place, headed for 100 losses. But then we started to play better baseball. Guys like Yaz and Tony were established, new guys like me and George Scott felt more comfortable, and the front office picked up some pitchers like Jose Santiago and Lee Stange that helped. We played very well in the second-half of 1966.”

THE IMPOSSIBLE DREAM SEASON

Dick Williams recognized Rico’s full potential from the very beginning. He knew his seriousness could be converted into leadership. He knew the emotionalism could be channeled into an intensity to win. He knew the histrionics were just a manifestation of Rico’s frustration at losing. He was the right manager for Rico at the right time.

Williams’ demonstration of confidence helped get Rico off to a great start in 1967. By the end of June, he was batting .296 with eight home runs and thirty-two RBI. He was playing at a level that would earn him a position on the ‘67 All Star team. But injury struck again when the Indian’s George Culver nailed him on the left wrist with a fastball.

Williams gave Rico the rest he needed. When Rico returned to the lineup, his average fell—he had dropped to .267 by the end of July—but he still fielded his position flawlessly, anchored the young infield, and got the job done.

Saturday, August 26 was a new day for the Red Sox. In a season of 162 games you can’t get too high after a win or too low after a loss. When you split a doubleheader, you just put it out of your mind and focus on the next game. The Sox—White and Red—remained tied and they were both one-half game off the pace following a Twins victory Friday night. It was going to be that kind of year.

Red Sox batters got off to a good start, drilling timely hits off Joel Horlen the White Sox starter. In the third inning, Jose Tartabull got things going with a triple that totally befuddled White Sox right-fielder Rocky Colavito. Adair, Yaz and Scotty all followed with singles and the Red Sox had jumped out to a 2-0 lead.

In the top of the fourth, with Mike Andrews at first after a walk, catcher Mike Ryan sent another triple in Colavito’s direction to score Andrews. After five innings the Red Sox had a semi-comfortable 3-0 lead.

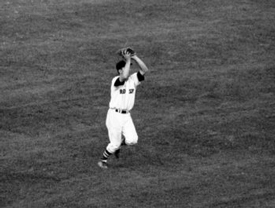

The Boston dugout was upbeat but they knew they had to get some more runs. Super-sub, Jerry Adair, got it rolling in the top of the sixth with a single. George Scott followed suit and Reggie Smith brought Adair home with a single of his own. Eddie Stanky brought knuckle-baller Wilbur Wood in from the bullpen to face Rico.

There was a certain irony as Rico dug in against the left-handed Wood. Wilbur had grown up dreaming of playing for the Red Sox and here he was trying to pitch them out of the pennant. Rico had grown up as a die-hard Yankees fan and here he was trying to propel their most-hated rivals to the pennant. And both of them were playing for serious money a thousand or so miles from their boyhood homes.

Rico thought, “knuckleball,” “contact,” and “patience” as he waited for Wood’s delivery. His patience was rewarded as he lined a knuckle ball into left center and he lit out in the direction of first. Scott was home easily as Rico picked up the sign from first base coach, Bobby Doerr, to leg it for second. Rico went in to second standing up since the White Sox were more interested in holding Reggie Smith at third. Rico’s RBI had given Boston a five-run cushion and the Red Sox went on to an easy 6-2 victory.

For Rico Petrocelli, it was just another day at the ballpark. He had fielded flawlessly and kept the hyperactive Stephenson settled down. He felt that he had redeemed himself for the base running gaffe of the night before with his key double in the Saturday game. He was pleased with his day’s work but it was just one more game in a 162-game season.

THE LATER YEARS

Rico’s distinguished Red Sox career covered thirteen years, including his brief stint as a twenty-year old at the end of the 1963 season. The 1967 season will always stand out as the year he came of age, the year he became a stable veteran. And what does Rico remember best about 1967?

“What I remember most is the way we meshed as a team that year. Nobody gave us a chance at the beginning of the year, but we believed in ourselves. Some of us had been around for a while, then we had a bunch of rookies, and we added players during the year and we all managed to come together. We had our share of laughs and pranks, but these were all classy guys, good people,” he emphasized.

“And I have to mention the fans,” he added. “Players will say that the fans cheering don’t matter but they do, especially that year. In 1967, they started filling the ballpark and cheering us on. If you struck out you could almost hear them say, ‘That’s okay. You’ll get them the next time.’”

Rico’s peak years were probably 1969-1971. During those three years, he played in almost every game, averaged over thirty home runs and knocked in nearly an average of 100 runs each year. In fact he was tops on the Red Sox for home runs and RBI during that three-year period. In 1969, he socked forty home runs and batted .297. His 40 home runs stood as the American League record for shortstops until ARod hit 42 in 1998. Not too bad for a hitter who was considered so marginal that he tried switch-hitting!

Rico was inducted into the Red Sox Hall of Fame in September, 1997. “I am really proud of that,” he said. “There are some really great players in there including teammates like Yaz, Jim Lonborg and George Scott. It’s an honor just to be included with all those great players.

Rico was inducted into the Red Sox Hall of Fame in September, 1997. “I am really proud of that,” he said. “There are some really great players in there including teammates like Yaz, Jim Lonborg and George Scott. It’s an honor just to be included with all those great players.

Rico is currently enjoying retirement. He spends part of the year in southern New Hampshire and part of the year in Florida. Best of all, Rico and his wife Elsie, who celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary in 2015, get to spend lots of time with their four sons and their grandchildren.

When asked to characterize what the 1967 season meant to him personally, Rico replied, “It really affected me. It has influenced where I live, what I do, who I am. It really is a part of me. When people think of me they say, ‘you’re the guy who played for the 1967 Red Sox.’ And I am.”

Yes you are, Rico. Yes, you are!

********************************************************************************************

This feature has been excerpted from the recently released The Impossible Dream 1967 Red Sox: Birth of Red Sox Nation To purchase a copy signed and inscribed as you direct by author Herb Crehan go to “Books.“

Leave A Comment