When the Boston Red Sox spring training camp opened in Winter Haven, Florida, in late-February 1967, nobody was talking about an American League pennant or humming Broadway show tunes in the team’s honor. The 1966 Red Sox had finished in ninth place, a distant twenty-six games behind the World Champion Baltimore Orioles, and the team had lost a total of one hundred and ninety games over two seasons. Las Vegas odds maker Jimmy “The Greek” Snyder thought so little of the team’s chances that he rated them as 100-1 underdogs in the 1967 American League pennant race.

Baseball has always been the number one passion among New England sports fans. But in 1966 the Red Sox had averaged only about 10,000 fans per game, and the previous season’s attendance at Fenway Park had totaled just 652,201. New England sports fans followed stories from the Red Sox training camp as a harbinger of spring, but they were more excited about the Boston Celtics who were trying to extend their streak of eight straight World Championships, and the Boston Bruins who featured a rookie defenseman by the name of Bobby Orr.

ROOKIE MANAGER

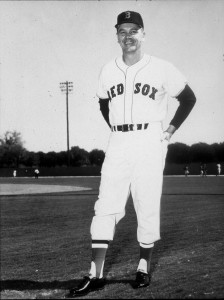

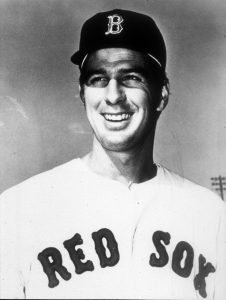

Red Sox rookie manager, Dick Williams, didn’t share in the apathy surrounding the 1967 Red Sox. “I thought we would be a pretty decent team,” Williams recalled prior to his induction to the Red Sox Hall of Fame in November, 2006. He quickly added, “I never thought for a minute that we would end up winning the American League pennant and playing in the seventh game of the World Series, but I knew we had some good young talent.”

Dick Williams had played for thirteen seasons in the major leagues and finished his career with the Red Sox in 1964. As a younger player, Williams was a highly regarded prospect who broke in with the powerful Brooklyn Dodgers in 1951. The following season he suffered a three-way shoulder separation that turned a potential All-Star into a well-traveled big league jack-of-all-trades overnight.

Dick Williams had played for thirteen seasons in the major leagues and finished his career with the Red Sox in 1964. As a younger player, Williams was a highly regarded prospect who broke in with the powerful Brooklyn Dodgers in 1951. The following season he suffered a three-way shoulder separation that turned a potential All-Star into a well-traveled big league jack-of-all-trades overnight.

Reflecting on his 1952 injury, Williams offered, “In the next eleven years, I was traded six times, spent time with five different organizations, and played four different positions. And I had to become a smarter player,” he emphasized. “I spent a lot of time studying strategy and human nature. That injury put me on track to becoming a manager.”

At the end of the 1964 season, Red Sox Farm Director Neal Mahoney offered Williams a job as a player/coach for the Red Sox Triple A farm team in Seattle. When the Seattle franchise was moved to Toronto prior to the 1965 season, Williams was named to manage the club. He led Toronto in back-to-back championship seasons, and in October 1966 he was named to manage the Boston Red Sox. The 37-year-old Williams became the youngest manager in the American League.

At the press conference announcing his appointment, Williams promised Boston fans “a hustling team.” He declined to predict where the team would finish but he did promise improvement. And he left no doubt about who was in charge. Asked if the 1967 Red Sox would have a team captain, he responded, “No, I’m the only chief. The players are the Indians.” When writers reminded Williams that Carl Yastrzemski was the incumbent captain, he answered, “We won’t have one next year.”

Enterprising, young Boston Globe reporter Will McDonough made a bee-line to the Yastrzemski residence in Lynnfield, MA, for a reaction. If he expected Yaz to be upset by his “demotion,” McDonough must have been disappointed. “Happy is not the right word,” Yaz responded. “Relieved is a better word,” he continued. “To be honest, I never wanted to be captain. Now that I’m not, I feel like a weight has been taken off my shoulders.”

BACK TO BASICS

Asked if he remembered being nervous just before camp opened, Williams answered, “I wouldn’t say I was nervous, because I knew I could do the job. But I was certainly apprehensive. I had never run a big league camp before. I had run two spring camps for Toronto but that’s the minor leagues and it’s different.

“I was fortunate that I had a great coaching staff,” Williams emphasizes. “They were a big help organizing the camp. Eddie [“Pop”] Popowski had been in the organization for many years and he had managed most of our players in the minors. Bobby Doerr was just great and he had the respect of everyone. And Al Lakeman had been on the staff the year before so he gave us some continuity. But Sal Maglie’s [pitching coach] wife was critically ill so he couldn’t be there when the camp opened.”

Williams shook his head when he considered the number of coaches, instructors and the sophisticated equipment on hand at spring training today. “I’m happy for the managers and all the resources they have today. But in 1967 it was just me and my three coaches, and four when Sal was able to get down there. Ted Williams was supposed to help out with the hitters but he was more interested in talking to the pitchers about throwing the slider,” Dick Williams chuckled. “Dom DiMaggio did come down after the camp had opened and he helped us with the outfielders.”

Dick Williams was determined to stress fundamentals with his 1967 Red Sox team. He firmly believed that attention to detail made a big difference over a 162 game season.

“I grew up in baseball with the Brooklyn Dodgers system and we were grounded in baseball fundamentals from the beginning. We used to talk about doing things the Branch Rickey [legendary Dodgers general manager and Baseball Hall of Fame member] way, ‘the Dodger way.’ I wanted to make sure that our players knew how to play the game the right way.

“We spent the first two and one-half days of spring training in 1967 working with the whole team on fundamentals. We started out with the on-deck circle and worked our way around the infield. I was amazed that most of our players didn’t know what the double line down the first base line meant,” Williams marveled at the memory. “We stopped going over the fundamentals when we finished with third base. When you’ve got Carl Yastrzemski in left field and Tony Conigliaro in right, you figure the outfield is pretty well taken care of.”

WAKEUP CALL: 7 AM

When Dick Williams addressed his twenty-four pitchers and four catchers on the first day of spring training, he made it clear that things would be different at the 1967 camp. Williams emphasized that workouts would be tightly organized and that drills would be scheduled down to the minute. But apparently pitchers Dennis Bennett and Bob Sadowski didn’t get the message. The two roommates arrived twenty-five minutes late on the third day of camp, and then blamed the hotel switchboard operator for not placing their wake-up call.

“I was furious,” Williams recalls. “But I knew how to solve it. I went into my office and called the switchboard operator at the Holiday Inn [Red Sox spring training headquarters]. I told her to call all the players at 7 AM every morning. Since workouts began at 10 [AM], I knew everyone would be on time. Then I called the two of them [Bennett and Sadowski] into my office and told them, ‘This will not happen again!’”

Dick Williams declined to discuss the Bennett-Sadowski incident at his daily press conference, but he did tell reporters that he planned to let rookie Tony Horton battle incumbent George Scott for the regular first base position. He added that he would try Scott in the outfield and other infield positions during the spring. As spring training went on, Williams and Scott would spar on a number of issues, including where George would play and his on-going battle to get down to a reasonable playing weight.

“George didn’t like my moving him around the field that spring,” Dick Williams remembered clearly. “What he didn’t realize was that I considered him to be one of our best athletes and I knew he could play almost anywhere. Horton could only play first base and we needed to see what he could do. I was pretty sure that the Boomer [Scott] would be our everyday first baseman, and the spring is when you work those things out,” he emphasized.

“George didn’t like my moving him around the field that spring,” Dick Williams remembered clearly. “What he didn’t realize was that I considered him to be one of our best athletes and I knew he could play almost anywhere. Horton could only play first base and we needed to see what he could do. I was pretty sure that the Boomer [Scott] would be our everyday first baseman, and the spring is when you work those things out,” he emphasized.

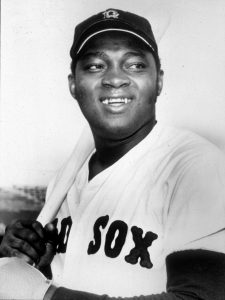

It is somewhat ironic that George Scott and his nemesis from the spring of 1967, Dick Williams, were inducted into the Red Sox Hall of Fame together in November 2006. But the passage of nearly forty years had given George Scott a different perspective on their disagreements that spring. “We didn’t know how to study the game,” Scott said at the time of his induction. “Dick Williams showed us how to do it that spring. He pressed the right buttons for everyone on that team.”

YOUR SERVE!

Dick Williams was determined to use every minute in spring training camp productively. With that in mind, he set up volleyball net in foul territory down the leftfield line so the pitchers could get in some additional conditioning work. “If the pitchers weren’t throwing or running I wanted them to be active playing volleyball. Usually pitchers stand around in the outfield going through the motions of shagging fly balls. But mostly they just stood around talking, which didn’t do them any good.”

Pitcher Jose Santiago, who would go on to win twelve games for the 1967 Red Sox, remembers the volleyball games fondly. “Playing volleyball if we weren’t working on our pitching was a lot of fun. It was boring standing around in the outfield watching the hitters bat. Like most of the guys, I had played other sports and I thought volleyball helped get us in shape,” Jose remembered.

“That was Dick Williams for you,” catcher Russ Gibson remarked, “always thinking. Even if no one had ever tried it before, Dick wasn’t afraid to do something different.” Gibson, who had been a three-sport star at DurfeeHigh School in Fall River, Massachusetts, knew Williams better than most of the players. Russ had been the starting catcher, and a player-coach, under Dick Williams in Toronto in 1965 and 1966.

Another Williams’ innovation was the use of videotape to help players to correct their flaws. “We may have been the first team to use videotape. If not, we were one of the first. And I have to credit Dick O’Connell [Red Sox general manager] for getting me everything I needed to do my job. If I needed something Dick made sure I got it.

“When I played for the Red Sox [1963-1964], Johnny Pesky was the manager. He was a good manager and a terrific guy. But his general manager [Mike “Pinky” Higgins] didn’t back him up; didn’t help him to do his job. I was very fortunate to have Dick O’Connell. He helped me any way he could,” Williams declares emphatically.

Dick Williams acknowledged that he had a unique advantage when it came to evaluating his 1967 team: he had either played with or managed most of the players. “I had managed Joe Foy, Reggie Smith, Mike Andrews, Gibby [Russ Gibson], and others at Toronto. And I had played with guys like Yaz and Dalton Jones. I roomed with Tony Conigliaro’s suitcase in my last year [1964],” Williams laughed. “So I knew what most of the guys could do.

“I knew I could count on Yaz for leadership on the field. And I knew he never really wanted to be captain. But even I didn’t expect the kind of year he had in 1967. He had as good a year as any ballplayer I have ever seen,” Williams insisted.

1967 TRIPLE CROWN WINNER

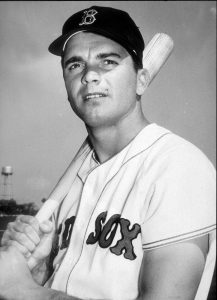

Carl Yastrzemski could prepare for the 1967 season without worrying about the ambiguous duties of a team captain. More importantly, Yaz reported to camp in the best shape of his professional baseball career. During his first six seasons in the big leagues he had won an American League batting title and he had achieved All-Star status three times. Now, at age 27, he appeared ready to take his place as one of the elite players in the game.

“One of the big differences in 1967,” Yaz related many years later, “is that I was able to work out the preceding winter. In earlier years, I was finishing up my college work in the off-season. But I had completed my degree at MerrimackCollege so I had time to focus on my conditioning. I reported to spring training in great shape.”

The previous winter Yaz had traveled regularly from his home in Lynnfield to the Colonial Resort in Wakefield, Massachusetts, working out under the direction of physical therapist Gene Berde. “Gene worked with me all winter. He let me know that he didn’t think I was in great shape when we first started,” Yaz recalls. “He really worked me hard and it paid off.”

The intensive regimen improved his stamina and made Yaz stronger at the plate. “I had a good spring training. I noticed right away that I had more power. The ball was going another thirty or forty feet. That’s when I decided to become a pull hitter. I felt I could help the ball club more by being a power hitter, so I made the transition in hitting style,” Yaz remembered.

Dick Williams knew that Yaz would be his every-day left fielder, and he felt the same way about twenty-two-year-old right fielder Tony Conigliaro. When Williams was introduced to the media the previous October he was asked to identify his regular players. The first name he mentioned was Yaz, and the second was Tony C. “I knew what Tony could do,” Williams acknowledged, “And I wanted his bat in the lineup every day. There was never any question who my right fielder would be.”

Local boy Conigliaro was beginning his fourth season with the Boston Red Sox. His right-handed swing was seemingly tailor-made for FenwayPark, and he had topped the American League with 32 home runs in 1965. Tony got off to a great start in March 1967, homering in the Grapefruit League season opener in Sarasota, Florida, against the Chicago White Sox. Then four days later, when the White Sox came to Winter Haven, he greeted them with a home run and two doubles.

But the Red Sox and Tony got a scare on March 18 when teammate John Wyatt drilled him in the left shoulder with a batting practice fastball. He was flown back to Boston where x-rays showed a slight crack of the shoulder. It was the fifth time in five years with the Red Sox that Tony had a bone broken by a pitched ball. Fortunately, the injury was not serious. Conigliaro returned to Florida and resumed his slugging ways.

CAPTAIN OF THE INFIELD

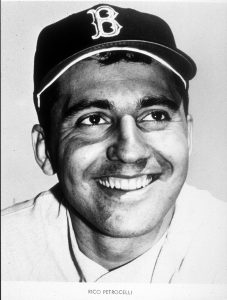

Dick Williams didn’t want a team captain, but he did want someone to take charge of the infield. And he recognized that Rico Petrocelli, who was beginning his third season as the regular shortstop, had the potential to fill that role. Williams told the writers, “This I believe would be a perfect job for Rico. He’s an intelligent ballplayer and I want him to have some authority out there. So I told him that I wanted him to take over in tight spots.”

Williams was a tough disciplinarian but he also was an astute judge of talent. And he understood that some players needed special handling. He and coach Eddie Popowski went out of their way in spring training to make sure that Rico was comfortable. And their patience was rewarded when Rico was selected for the American League All-Star team in mid-season.

Looking back, Rico remembered how much being selected as “captain of the infield” meant to him. “Dick showed a lot of confidence in me, and gave me a lot of responsibility. It really meant a lot to me. For the first time,” Rico says, “I really felt like a big leaguer, like I really belonged out there.”

Another infielder that Williams singled out as a likely regular was third baseman Joe Foy. Foy had been a key player for Williams in Toronto in 1965, when Joe was named the Most Valuable Player of the International League. After a slow start as a rookie with the Red Sox in 1966, he came on strong in the second half and led the team in runs scored.

Dick Williams was watching Foy’s weight almost as carefully as he watching George Scott on the scales. Foy had reported at 211 pounds and the manager wanted him to drop at least 6 pounds. Williams told reporters, “We want to avoid another slow start for Foy, and the best way to do that is to make sure he is in playing shape.”

Tony Horton continued to get playing time at first base throughout the spring. Both Williams and Bobby Doerr liked his swing and the Red Sox were showcasing Horton for a possible trade. George Scott swapped off with Horton at first, spent some time at third base, and made several appearances in the outfield.

Scott’s outfield adventures came to an end on March 23 when the slugger knocked himself unconscious running into the right field wall in Winter Haven. “He was out cold for one minute,” trainer (and future part-owner) Buddy LeRoux told reporters. “He moved the wall from 330 feet to 332,” second baseman Mike Andrews offered. Scott was kept overnight at Winter Haven Memorial Hospital as a precaution, but his only injury was a bruised wrist. On March 28 Dick Williams announced, “As soon as Scott is ready to play, he will go immediately to first base.”

TORONTO CONNECTION

In addition to Russ Gibson and Joe Foy, there were several other candidates for spots with the 1967 Red Sox who had played for Dick Williams in Toronto. Mike Andrews was a strong candidate to take over as the regular second baseman and Reggie Smith was positioned to become the starting center fielder. Both players had excelled in Toronto, but both knew that Williams wouldn’t show them any favoritism.

Mike Andrews remembered that the success in Toronto carried over to training camp in 1967. “Reggie Smith, Russ Gibson and I were all rookies in 1967, and we had won the International League championship the year before in Toronto, so we didn’t think about losing. And we knew Dick Williams didn’t want to hear about losing. I don’t think anyone thought about the second-division that spring.”

Reggie Smith was twenty-one years old when he reported to training camp at the end of February. When Dick Williams looked back on 1967 he talked about Reggie Smith’s athleticism. “Reggie was probably the best athlete on our team,” Williams believes. “He really could do it all. I know when he was taking some headfirst slides in spring training games that he opened some eyes. When Mike Andrews came down with a bad back I put Reggie at second base. He was such a good athlete that I knew he could handle it.”

Dalton Jones, who had spent the three previous seasons with the Red Sox, was the obvious choice as the team’s backup infielder. The versatile George Thomas was slotted as a spare outfielder and to play in the infield if needed. In fact, when the writers were pressing Williams to name his regular lineup, Williams answered “possibly George Thomas” for all nine positions.

Haverhill, MA, native Mike Ryan had caught 116 games for the Red Sox in 1966 and he was highly-regarded for his defense. It seemed clear that Ryan and Gibson would share the catching duties, leaving veteran receiver Bob Tillman for spot- duty behind the plate.

1967 CY YOUNG WINNER

When spring training camp opened, Dick Williams’ number one concern was his pitching staff. “I knew we would score runs, that we had a strong lineup. And I thought we could improve our defense. But I wasn’t sure about our pitching.” Echoing a time-honored refrain, he added, “You can never have enough pitching.”

One pitcher that Williams was counting on was right-hander Jim Lonborg, who had shown plenty of promise during his first two seasons with the club. “Lonborg was one player who I had never seen. I didn’t play with him and I didn’t manage him. But when I got a look at him that spring I knew he would help us. He had good stuff and he was a hard worker,” Williams observed.

Lonborg was determined to have a good year in 1967. He had pitched winter ball in Venezuela and he reported to camp in great shape. He remembers how organized the camp was that spring. “Dick [Williams] was very purposeful. If we weren’t throwing or running wind sprints, he had us playing volleyball. He kept us focused all season long.”

Lonborg won his third game in three decisions on March 20, and he was emerging as the ace of the staff. He told reporters, “I want to be the Opening Day pitcher. It would be quite an honor and it would mean the manager thinks I’m the best on the club.” He added, “I’d like to pitch between 260 and 270 innings this season.”

Williams made it clear to his players and the media that he had no patience with sore-armed pitchers. In mid-March he told writers that he intended to carry “three catchers, six outfielders, seven infielders, and only healthy pitchers.” At that time he listed Lonborg, Santiago, Darrell Brandon, Lee Stange, and Hank Fisher as his likely starters.

One unheralded rookie pitcher who was making an impression was skinny, 21-year-old Billy Rohr. The left hander made several impressive appearances in exhibition games and appeared likely to pitch his way onto the roster. Veteran pitchers Dan Osinski and Don McMahon, along with young left hander Bill Landis, were the leading candidates for middle relief. John Wyatt was a lock to close games for the Red Sox if he could ever find his way out of Dick Williams’ doghouse. Wyatt had incurred his manager’s wrath when he hit Tony Conigliaro with that pitch in batting practice, and he was working his way back into Dick Williams’ good graces.

LOOKING BACK

The Boston Red Sox finished their spring exhibition games with a record of fourteen wins and thirteen losses. And while they had tried their manger’s patience at times with fundamental missteps, in general Williams was pleased with his team. “I liked the way we had come together as a unit. As the spring went on I saw players pulling together more and more. That had been missing from other Red Sox teams.”

Veteran Boston Globe columnist Harold Kaese penned an upbeat assessment of Williams and his ball club in late March. “Williams is away to a good though somewhat controversial start,” Kaese told readers. “The Red Sox are probably playing more inside baseball now than they have for any manager since Bill Carrigan [Red Sox manager from 1913-1916 and 1927-29]. Williams has his players doing more than swinging bats. He has them running, bunting and thinking.”

As spring training came to an end, the Boston writers pressured Dick Williams for a prediction on the upcoming season. Williams finally offered one of his best-known quotes: “We will win more than we lose.” For a club that had lost ninety games the year before that seemed like an optimistic forecast.

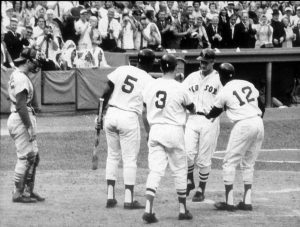

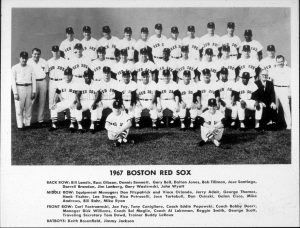

The Red Sox team that emerged from the 1967 training camp was a very young club. When they took the field on Opening Day at FenwayPark on April 12 before a “crowd” of 8,234 fans, their average age was only 24 years old.

The 1967 Boston Red Sox did indeed win more games than they lost. But they did so much more than that. They captured the hearts and minds of New England fans and they restored a regional pride in the Boston Red Sox. And they built the foundation that Red Sox Nation rests upon today.

***********************************************

Portions of this article originally appeared in The Impossible Dream 1967 Red Sox: Birth of Red Sox Nation.

To order your copy of The Impossible Dream 1967 Red Sox: Birth of Red Sox Nation click here

Leave A Comment