And just like that, the end was in sight. After two hours and fifteen minutes of suspense, all of a sudden the Red Sox were three outs away from at least a share of the American League pennant. The crowd knew that the Tigers had defeated the California Angels 6-4 in the first game of their doubleheader, keeping Detroit’s hope for a first-place tie alive, but the fans at Fenway Park were totally focused on the outcome before them. A low murmur could be heard throughout the ballpark. It was if half the fans turned to their companions and said, “You know, I think this is really going to happen!” And half of the crowd replied, “There is a lot that could go wrong.” Jim Lonborg was four years old when Boston lost the 1946 World Series, and he grew up in California so he had a clean slate. He was completely confident that he could find the strength in his strong right arm to nail down the victory.

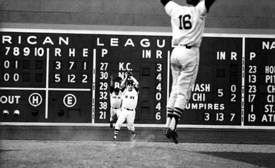

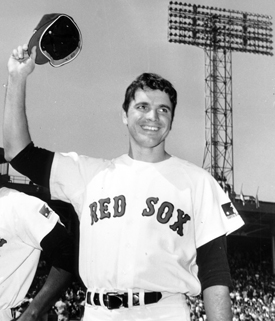

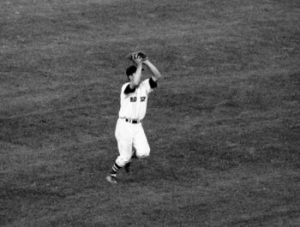

Lonborg recalls, “I remember that my last pitch of the game was a fastball to Rollins. At that time I was just throwing fastballs, one after another. I was really pumped up and I was in my groove. I didn’t have to go with much of anything else. We had runs to work with. It wasn’t a matter then of having to trick somebody at the plate. It was just a matter of going straight in at the hitter.” For sheer drama, the sky-high popup that Rollins hit towards Petrocelli at short can only be compared to one other batted ball: the fly ball that Roy Hobbs hit off the light tower in “The Natural.” In reality, Rollins’ ball was a looping pop-up but to Red Sox fans it seemed to go up forever. As it reached the peak of its arc, it seemed to have become suspended for a split second. For that split second Red Sox fans throughout New England—the nation really—held their collective breaths. They almost seemed to be saying in unison “this can’t be happening; this is only a dream and I’ll wake up in a second.” Rico Petrocelli told me later, “That may have been the easiest play I had to make all year. But while I was waiting for it to come down, I was saying, ‘Please Lord, let me catch this ball!’” Then the ball began its downward descent, gaining in acceleration just like a roller coaster. Suddenly, it was in Petrocelli’s glove and time stood still for another split second. An alert cameraman near the Red Sox dugout captured this scene with one single frame of film. It shows Lonborg poised to celebrate on the mound . . . Rico grasping the ball as if it were his first born . . . Yaz beginning his dash in from left field . . . and . . . most importantly, over Yaz’s shoulder the iconic scoreboard reading “Boston 5, Minnesota 3.”

That is how the Red Sox 162nd game of the regular season ended. That is how the 1967 Red Sox became the last major league team ever to win the league pennant on the last day of the regular season.

But how did it begin?

YAZ SIR: THAT’S MY BABY!

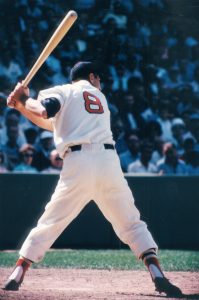

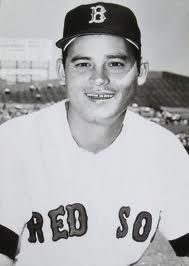

The first seed of the Impossible Dream 1967 Red Sox was planted in 1958 when the club signed 19-year-old Carl Michael Yastrzemski to a sizable bonus after his freshman year at Notre Dame. Yaz began his career with the Red Sox Raleigh, NC, farm team where he hit .377 playing mostly (104 games) at second base.

The next season Yaz was promoted to the Red Sox Triple-A club the Minneapolis Millers for the 1960 season. He hit .339 against International League pitching and shifted to left field as the heir-apparent to Ted Williams.

Yaz had a difficult time with major league pitching batting only .266 in 1961, his rookie season. But over the next five seasons he averaged near to .300 and hit 15-20 home runs. He kept his promise to his parents, graduating from Merrimack College in 1966, so he was able spend the winter before the 1967 season getting in shape.

The next important step was signing local boy Tony Conigliaro after he graduated from St. Mary’s of Lynn in 1962. Tony C burned up the New York-Penn league with Wellsville (NY) in 1963 and took the Red Sox 1964 spring training camp by storm. Johnny Pesky told me, “I had to bring the kid to Boston or the fans would have killed me.

Tony hit 24 home runs as a rookie and became the youngest player—age 20—to win the AL home run race in 1965. After driving in 93 runs in 1966, Tony was looking forward to his best season in 1967.

Tony hit 24 home runs as a rookie and became the youngest player—age 20—to win the AL home run race in 1965. After driving in 93 runs in 1966, Tony was looking forward to his best season in 1967.

The Red Sox signed Rico Petrocelli right out of high school in 1961, and quickly earmarked him as their shortstop of the future. The club signed pitcher Jim Lonborg in 1963 after he completed his junior year at Stanford.

By 1965 both Rico and Lonborg were regulars for the Boston Red Sox. As Rico said, “Neither one of us belonged in the big leagues. But there was no one else. We took our lumps but we learned on the job.” In 1967 they would both make the AL All-Star team along with Yaz and Tony C.

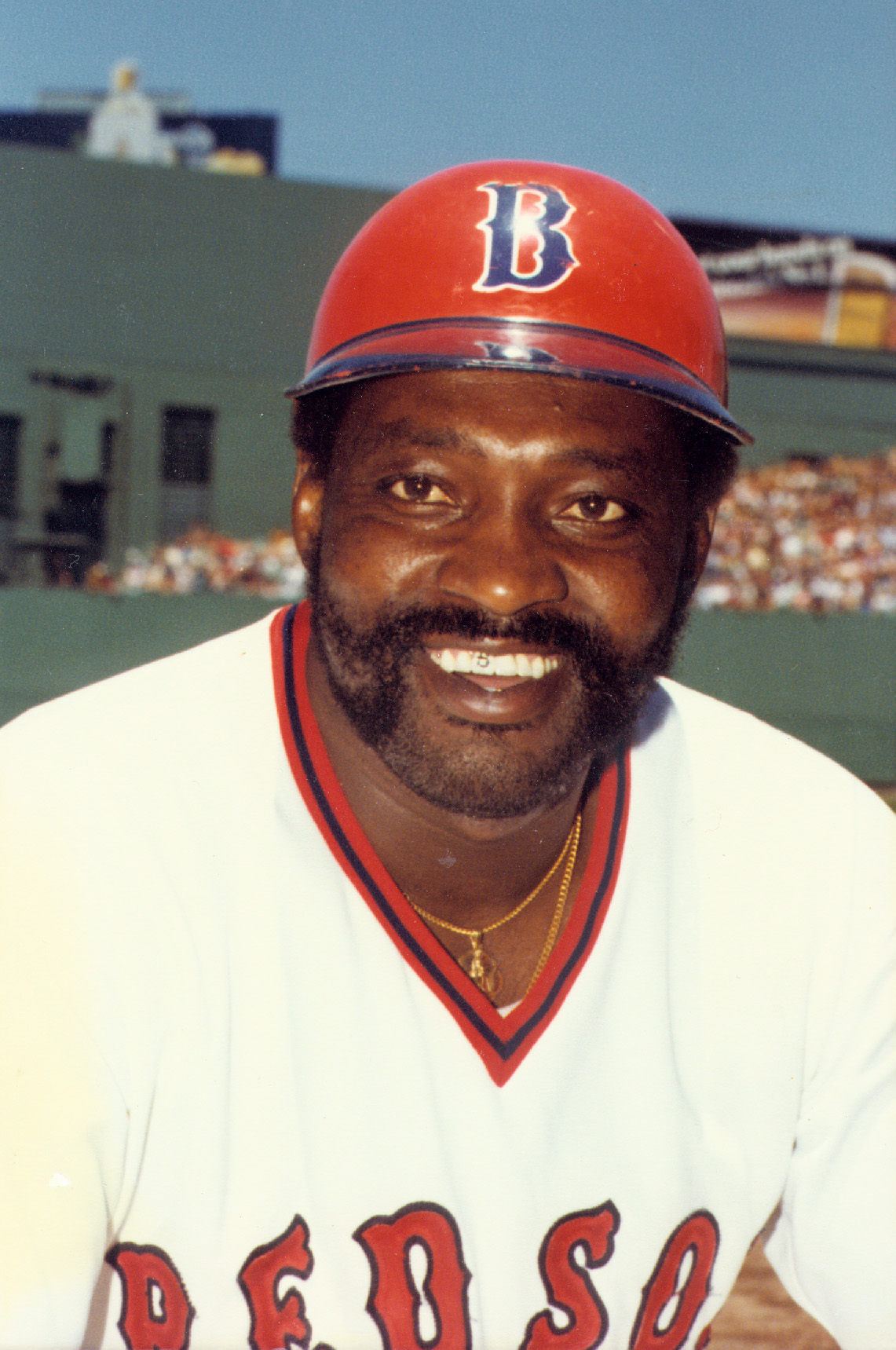

Future first baseman George Scott was discovered in Greenville, MS, by Red Sox scout Ed Scott who had been hired by the Red Sox specifically to identify African-American prospects. Scott was signed by the Red Sox on the night of his high school graduation in 1962 and less than four years later he was the starting first baseman for the Red Sox in April 1966.

SHARP-EYED SCOUTS

Third baseman Joe Foy and center fielder Reggie Smith had both been originally signed by the Minnesota Twins and both of them played their first professional baseball season in the Twins minor league system. They both struggled in their first seasons and Minnesota failed to protect them on their 40 man roster. Red Sox scouts identified them both as high potential prospects and Foy was drafted from the Twins in 1962 for $8,000 and Smith was plucked from the Twins’ organization one year later for the same bargain price.

Foy had a solid rookie season for the Red Sox in 1966, and Reggie debuted with Boston in 1967. Ironically, when the Red Sox met the Twins in the crucial series played the last weekend of the season, the Twins weakest two starting positions were third base and center field.

Mike Andrews signed with the Red Sox in 1961 after one year at El Camino Junior College in Torrance, CA. Andrews shadowed Rico Petrocelli as a shortstop in the minor league system until he was shifted to second base in Toronto in 1966. Andrews made the transition flawlessly and he was the regular second baseman for the 1967 Red Sox.

The 1967 AL Pennant-winning Boston Red Sox never had an everyday catcher but two local boys, Mike Ryan of Haverhill, MA, and Russ Gibson of Fall River, MA, caught more games than anyone else. Ryan, who caught 79 games in 1967, was signed by the Red Sox in 1960, and spent five years in the Red Sox minors before arriving in Boston to stay in 1966. Gibson, who had been a legendary schoolboy athlete at Fall River’s Durfee High School, had spent 10 years in the Red Sox minor league system before finally arriving in Boston as a 27-year-old rookie in 1967.

Every 1967 position regular was a product of the Red Sox system. Utility infielder Dalton Jones, who still holds the Red Sox career record for pinch-hits, had spent three years in their minors before breaking in with the Red Sox in 1964. And catcher Bob Tillman and first baseman Tony Horton, who were with the 1967 Red Sox until mid-season trades, came through the Red Sox system.

TORONTO TO BOSTON SHUTTLE

There were five pitchers in 1967 that spent part of the year at Triple-A Toronto and part of the year in Boston, and all five of them came of age in the Red Sox minor league system. The most successful Canadian export was Al “Sparky Lyle” who fittingly returned to the states on the Fourth of July. Sparky, who would later win a Cy Young award with the Yankees, was originally signed by Baltimore but was plucked from the Orioles in the first-year draft in 1964. Lyle made 27 relief appearances in 1967, winning one and saving five games.

Billy Rohr will always be remembered for his one-hitter against the Yankees in his major league debut. He had been signed by the Pirates and hidden away by Pittsburgh but the Red Sox weren’t fooled and drafted Rohr in 1963. He had spent three years in the Red Sox minors before making the Red Sox as a 21-year-old.

Gary Waslewski of Meriden, CT, will never have to buy a beer in New England thanks to saving the day for the Red Sox in Game Six of the 1967 World Series. Waz was also signed by the Pirates, but never made it above double-A until he was drafted by the Red Sox in 1964. He flourished in Triple-A with the Red Sox and he had two stints in Boston in 1967.

Gary Waslewski of Meriden, CT, will never have to buy a beer in New England thanks to saving the day for the Red Sox in Game Six of the 1967 World Series. Waz was also signed by the Pirates, but never made it above double-A until he was drafted by the Red Sox in 1964. He flourished in Triple-A with the Red Sox and he had two stints in Boston in 1967.

Dave Morehead signed with the Red Sox in 1961 and two years later he was pitching for the Red Sox in Boston. He had made 95 starts for the Red Sox by his 23rd birthday, and he appeared headed for greatness when he threw a no-hitter in September 1965. But he injured his arm in 1966, and spent most of 1967 in Toronto. He was called up to the big club on August 1 and won five games between then and mid-September.

Jerry Stephenson, who was tabbed as the man with the golden arm, signed with the Red Sox in 1961. The son of legendary Boston scout Joe Stephenson, Jerry had already spent all or parts of three seasons with the Red Sox when spring training started in 1967. But Dick Williams sent to Toronto for seasoning, and he didn’t return to Boston until mid-August. Jerry started six games down the stretch and contributed with three victories.

Pitcher Galen Cisco deserves a category all his own. He was signed by the Red Sox in 1958 and after spending four years in the Red Sox minor league system he was called up to the Red Sox near the end of 1961. Cisco began the 1962 season in Boston with the Red Sox but he was placed on waivers that September and picked up by the New York Mets. When the Mets released him in 1966 he was re-signed by the Red Sox and pitched in 11 games for the 1967 Red Sox.

Finally, Ken Paulson was called up as a utility infielder in July of 1967 and appeared in five games for the 1967 Red Sox, and pitcher Ken Brett was called up near the seasons end, pitching in one regular season game and one World Series game. Both players came directly from Red Sox minor leagues.

All ten of the regular 1967 Red Sox position players were products of the team’s minor league system. The club’s best pitcher, Jim Lonborg, was a product of the clubs farm system, and six other pitchers who appeared in eight or more games in 1967were developed in the Red Sox minor league system.

In total, 21 of the 39 players who appear on the roster of the 1967 Red Sox were products of the Boston Red Sox farm system.

THE KANSAS CITY CONNECTION

When Dick O’Connell was named as general manager of the Red Sox in 1965, one of his first decisions was to hire Haywood Sullivan as the Director of Player Personnel. Sullivan had played in the Boston organization as a catcher for nine seasons, but the newly-formed Washington Senators selected him in the 1960 expansion draft and then traded him to the Kansas City A’s.

Sullivan had split his time between Kansas City and their minor league system from 1961 to 1963. In 1964 he managed the A’s Birmingham club in Double-A, and the following season he was promoted to their Vancouver team in Triple-A. But in mid-May, at age 34, he was named to manage the big league club in Kansas City. He finished the season at 54-82, and he was scheduled to return in 1966, but when the security of his original MLB team beckoned in Boston he grabbed it.

During his five seasons with Kansas City Sullivan had played and managed at both the big league and minor league level. Given the various roles he performed he knew the A’s organization from top to bottom. And he knew there were a number of players who were under-valued by the A’s that would flourish in the stability of the Boston franchise.

A total of five players that played a significant role with the 1967 Red Sox were acquired directly from the Kansas City A’s by the O’Connell-Sullivan combine.  The first player was pitcher Jose Santiago who was obtained in a straight-cash deal before the 1966 season. He played a critical role in 1967, appearing in a total of 50 ballgames. He made 39 relief appearances and 11 starts, including the key 161st game win over the Minnesota Twins.

The first player was pitcher Jose Santiago who was obtained in a straight-cash deal before the 1966 season. He played a critical role in 1967, appearing in a total of 50 ballgames. He made 39 relief appearances and 11 starts, including the key 161st game win over the Minnesota Twins.

In June 1966, the Red Sox traded outfielder Jim Gosger and two pitchers for outfielder Jose Tartabull and reliever John Wyatt. Tartabull played in 115 games adding to the outfield defense and he will always be remembered for throwing out the White Sox Ken Berry for the final out in a critical win in late August. John Wyatt was the closer for the 1967 Red Sox and he pitched in a club-leading 60 games winning 10 games, saving 20 others, and taking the ball whenever he was called upon.

The next addition from Kansas City was little-remembered left-handed pitcher Bill Landis. Landis was a “Rule-5” selection by the Red Sox prior to 1967 and under that rule the Red Sox had to keep him all season, or return him to the A’s and forfeit their payment. Landis remained with the Red Sox serving as a left-handed specialist and he made 19 appearances.

The last Kansas City player to join the 1967 Red Sox was the most-flamboyant and the least-expected. After A’s outfielder Ken “Hawk” Harrelson criticized owner Charlie Finely for his treatment of terminated Kansas City manager Al Dark, Finley gave Harrelson his outright release. The Hawk was a free agent and he signed with the Red Sox in late August to play right field in place of Tony Conigliaro.

OTHER IMPORTANT MOVES

But the Red Sox brain trust didn’t limit their creative deal-making to the Kansas City A’s. Probably the best trade they made was with the Cleveland Indians in mid-1966, when they traded reliever Dick Radatz, who had peaked in 1964, for starter Lee Stange and reliever Don McMahon. Stange pitched in 35 games in 1967, starting 24 of them and relieving in 11. Lee pitched in 181 innings, second only to Jim Lonborg.

Don McMahon pitched well for the Red Sox in the first two months of 1967, and more importantly he was the bargaining chip that allowed the Red Sox to obtain Jerry Adair from the White Sox on June 2. Adair was the super-sub that filled in at second and third base even playing shortstop when necessary.

Two days after acquiring Adair, O’Connell pulled off another major trade sending little-used first baseman Tony Horton to the Cleveland Indians for starting pitcher Gary Bell. Bell was the number two-pitcher to back up Jim Lonborg that the Red Sox so badly needed. And Gary didn’t disappoint, going 12-8 with the Red Sox in the important last four months of the season.

Two days after acquiring Adair, O’Connell pulled off another major trade sending little-used first baseman Tony Horton to the Cleveland Indians for starting pitcher Gary Bell. Bell was the number two-pitcher to back up Jim Lonborg that the Red Sox so badly needed. And Gary didn’t disappoint, going 12-8 with the Red Sox in the important last four months of the season.

But GM O’Connell had one more important acquisition to make. On August 3, O’Connell picked up veteran catcher Elston Howard from the New York Yankees to provide leadership and playoff experience to the youthful Red Sox. Howard balked at the trade after spending his whole career with the Yankees but a phone call from owner Tom Yawkey persuaded him to make the move.

Dick O’Connell and Haywood Sullivan had made additional moves to put together the 1967 Red Sox. They had engineered a trade with the Houston Astros to pick up Darrell “Bucky” Brandon who pitched in 39 games, 19 as a starter and while contributing five wins. Jack-of-all-trades and master of relieving tense moments with his brand of dry-humor, George Thomas, was obtained from the Detroit Tigers.

In all, 18 players from other clubs had been acquired to assemble the 1967 Red Sox. These acquisitions were critical to the success of the AL pennant winners.

HOW DID THEY DO IT?

The 1967 Boston Red Sox could never have won the AL pennant without general manager Dick O’Connell. Dick made many great moves and he has never received the credit he deserves.

And every “baseball lifer” I have interviewed insists that Carl Yastrzemski had the greatest season they have seen when every game mattered. Over and over Yaz came through with the key base hit.

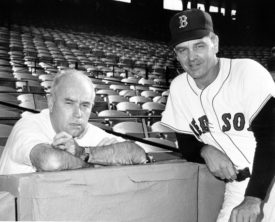

But the single individual who did the most to get the Red Sox to the World Series was 37-year-old manager Dick Williams. Williams had played for the Red Sox in 1963 and 1964, so he knew first-hand that the Red Sox were run like a country club. Williams changed the culture in the Red Sox clubhouse to a winning atmosphere from the first day of spring training.

And Williams had managed many of the 1967 Red Sox in Toronto, and he knew they shared his passion for winning. Dick Williams was completely candid in our several interviews and you will find that his memories are very revealing.

And Williams had managed many of the 1967 Red Sox in Toronto, and he knew they shared his passion for winning. Dick Williams was completely candid in our several interviews and you will find that his memories are very revealing.

The most important player was clearly Yaz. He was very relieved to be rid of the title “captain” so he could to do his leading on the field. No Yaz: no pennant! Yaz is a man of few words but you will find the words he shared with me to be meaningful.

The next most-important player was clearly “Gentleman Jim” Lonborg. He was the true pitching ace that you need to have to win the league-pennant. Eight of his twenty-two wins followed a Red Sox loss: the kind of consistency a team needs to avoid losing streaks. When you read what Jim has to say you will realize how intelligent and thoughtful he is.

Although his 1967 season ended tragically on August 18 when he was struck by a Jack Hamilton, Tony Conigliaro has to rank right behind Yaz and Lonnie. He had only played 95 games when he was injured but he had already hit 20 home runs and driven in 67 runners. When the team was just starting to believe in itself right after the All-Star game, Tony C made it seem that anything could happen. Reading what brothers Billy and Ritchie remember is likely to bring a tear to your eye.

The next most important player would have to be either Rico Petrocelli who solidified the infield, or George Scott who provided the consistent hitting, especially after Tony C went down. Rico was only 23 years-old when the season began but he was starting his third full season in the major leagues. You will find that Rico’s memories of Dick Williams are very different from his teammates.

And “Boomer” Scott or “Scottie” as he was known to his teammates went from the unpredictable player who always swung for the fences to a smooth hitter who batted .303 to finish fourth in batting in the AL. In addition to his clutch hitting Scott fielded his position at first base as well as any player in Red Sox history. You will want to read what the Boomer has to say about coach Eddie “Pop” Popowski and how he helped him to become a complete ballplayer.

Picking the next most important player isn’t that easy. And that’s partly because there was a different hero everyday it seemed. Possibly it was second baseman Mike Andrews for his steady influence at second base. Or it could have been reliever John Wyatt, who held the fort so often in his team-leading 60 appearances and 20 saves.

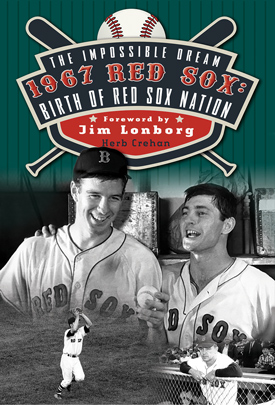

When you finish reading The Impossible Dream 1967 Red Sox: Birth of Red Sox Nation, you will have your own rankings. And when you win the league pennant by one game every player is important!

******************************************************************************************************************************************************************************

This feature has been excerpted from the recently released The Impossible Dream 1967 Red Sox: Birth of Red Sox Nation To purchase a copy signed and inscribed as you direct by author Herb Crehan go to “Books.“

Herb excellent as you talked about the 21 players that came from the Redsox farm system each player you named brought back memories of watching that season with my late brother(12 years older then I). I never knew Tony C came from saint Mary’s of Lynn I’ve been there for many high school basketball games as I was cheerleading coach slash team trainer because I was a nurse. I never saw anything in the school about Tony C . Can’t wait to read more!! Talk to you on The Remy Report.Fantastic writing!!!

The gym at St. Mary’s is named for Tony C. There’s a banner in far right corner with his name on it. At least it was there the last time I was there, about 5 or 6 years ago.

Great picture I had one also the record Gave them to a friend who collects RedcSox memories