When you think of Ted Williams and his Boston Red Sox playing career, you think of the Kid, the Splendid Splinter, Teddy Ballgame,

You think of .406 in 1941, .388 in 1957, the last of his 521 home runs in his last at-bat in 1960.

That career was star-studded aplenty: 18 All-Star Games, two Triple Crowns, two MVP awards, six batting championships, four home run titles, as well as two tours of military service.

But Ted didn’t just go away and hide in the Florida Keys or the MiramichiRiver in New Brunswick, Canada, and just fish, fish, fish when his playing days ended on a dreary Sept. 28, 1960.

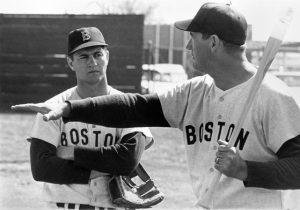

A lot went on after he “retired.” He was busy, busy, busy. He was at spring training in 1961, tutoring a youngster from a Long Island, New York, potato farm named Carl Yastrzemski, dispensing pointers to the heir apparent in left field.

In 1966, he was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame, with Casey Stengel, in Cooperstown. It was in that bucolic, upstate New York village that Ted issued his landmark call for the Hall of Fame inductions of the great players from the Negro Leagues.

During his induction speech on July 25, 1966, Williams declared, “I hope someday Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson will be voted into the Hall of Fame as symbols of the great Negro players who are not here only because they weren’t given the chance.”

Paige was inducted in 1971, Gibson in 1972, and others followed.

Ted surprised the baseball world again by accepting the managerial post of the Washington Senators in 1969. Not only did he replace Jim Lemon as field boss, he was named American League manager of the year that first season.

How did Williams do it? Lemon left a last-place team that finished with 65 wins and 96 losses in 1968. With Ted at the helm, in 1969, the Senators finished fourth with an 86-76 record – an astonishing 21 victories better, with many other statistical categories improved upon, too.

Ted remained with the team when the Senators moved to Texas and became the Rangers in 1972. They lost 100 games and Teddy Ballgame opted not to return for a fifth season in 1973.

He would spend time at his Ted Williams Baseball Camp in Lakeville, Mass.

He was free to fish a lot in the Seventies, divorce a third and final time, then showed up for Old-Timers Games at Fenway Park when the Red Sox initiated the fan-friendly events in the 1980s.

He was free to fish a lot in the Seventies, divorce a third and final time, then showed up for Old-Timers Games at Fenway Park when the Red Sox initiated the fan-friendly events in the 1980s.

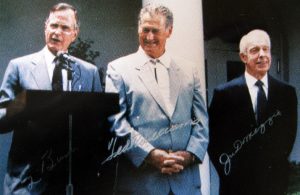

In 1991, Ted was recognized by President George Herbert Walker Bush on the 50th anniversary of his .406 batting average. Joe DiMaggio was alongside, honored for his 56-game hitting streak that won him selection as the league’s most valuable player.

No major leaguer has hit .400 since. No other major leaguer has hit safely in 56 straight games.

Also in 1991, Bush presented Williams with the Presidential Medal of Freedom. It is an award bestowed by the president and, along with the comparable Congressional Gold Medal – bestowed by an act of U.S. Congress – the highest civilian award of the United States. It recognizes those individuals who have made “an especially meritorious contribution to the security or national interests of the United States, world peace, cultural or other significant public or private endeavors.”

Before Ted would pass in 2002 and his body was placed in deep-freeze in a bizarre Arizona cryogenics laboratory, he would be honored with a Boston tunnel in his name.

They practically saved the best for last. The iconic scene of all-stars and All-Century players moving in on and surrounding a teary-eyed Ted Williams before the 1999 All-Star Game at FenwayPark is etched in the memories of all who witnessed it.

All of what occurred after Ted hung up his uniform on that day in 1960 would not have made such an impact were it not for his fiery, magnetic, larger-than-life persona that captured more than one generation.

He was loud, he was profane. No matter. He drew us in. No one else could walk into a room and stop it on a dime, dominate it, virtually force all eyes to focus unwaveringly on him.

As a young man all he wanted out of life was to walk down the street – could he really do that uninterruptedly? – and have people say, “There goes Ted Williams, the greatest hitter who ever lived.”

It’s not documented, but that figuratively, if not literally, happened for much of his 83 years.

He did wonderful things on the playing field, but there was more to him than that. We saw that after he played. For much of his life he did as he pleased – no dress ties, please – and pleased many of us along the way. All we could say was, “There goes Ted Williams—–”……you fill in the blanks!

Dick Trust’s new book, “Ted Williams and Friends: 1960 – 2002,” a photographic account, with text, of Ted’s post-playing career, has been released by Arcadia Publishing. To order a copy go to http://www.arcadiapublishing.com/9781467122948/Ted-Williams-and-Friends-1960-2002.

Or you may email the author directly at: rtrust68@comcast.net.

Very nice recollection of Ted. Would love to hear more.

I’m a sportswriter and was in the press box on the day of the Memorial for Ted. It was the most incredible event I have ever

witnessed. Whenever I’m asked what’s best sporting event I was ever at I always answer…”I’ve been to many “game sevens” in baseball, basketball and hockey, but the BEST EVENT wasn’t a game bit the Memorial for Ted at Fenway Park.