The Boston-Milwaukee-Atlanta Braves baseball club, the oldest continuously operating professional sports enterprise in the United States, spent the majority of its time right here in Boston. The team’s original ancestor was formed in 1871, predating the formations of the National and American Leagues in 1876 and 1901, respectively. Through their years in Boston, the Braves featured such players as John Clarkson, Kid Nichols, Hugh Duffy, Rabbit Maranville, Johnny Evers, Vic Willis, Rogers Hornsby, George Sisler, Wally Berger, Babe Ruth, Al Lopez, Sibby Sisti, Paul Waner, Tommy Holmes, Warren Spahn, Johnny Sain, Ernie Lombardi, Joe Medwick, Al Dark, Bob Elliott, Eddie Stanky, Del Crandall, Johnny Antonelli, Sam Jethroe, Lou Burdette, Johnny Logan and Eddie Mathews. Hank Aaron signed with them in 1952. The Boston Braves won a World Championship in 1914 and claimed the National League pennant in 1948. While the Braves haven’t called Boston home since the spring of 1953, their memory has not faded and is being preserved by a die-hard group of fans that formed the Boston Braves Historical Association in 1992.

The Boston-Milwaukee-Atlanta Braves baseball club, the oldest continuously operating professional sports enterprise in the United States, spent the majority of its time right here in Boston. The team’s original ancestor was formed in 1871, predating the formations of the National and American Leagues in 1876 and 1901, respectively. Through their years in Boston, the Braves featured such players as John Clarkson, Kid Nichols, Hugh Duffy, Rabbit Maranville, Johnny Evers, Vic Willis, Rogers Hornsby, George Sisler, Wally Berger, Babe Ruth, Al Lopez, Sibby Sisti, Paul Waner, Tommy Holmes, Warren Spahn, Johnny Sain, Ernie Lombardi, Joe Medwick, Al Dark, Bob Elliott, Eddie Stanky, Del Crandall, Johnny Antonelli, Sam Jethroe, Lou Burdette, Johnny Logan and Eddie Mathews. Hank Aaron signed with them in 1952. The Boston Braves won a World Championship in 1914 and claimed the National League pennant in 1948. While the Braves haven’t called Boston home since the spring of 1953, their memory has not faded and is being preserved by a die-hard group of fans that formed the Boston Braves Historical Association in 1992.

The City of Boston is famed for a number of historic trails that track a variety of notable events. Led by the renowned Freedom Trail, the Hub is also home to formal heritage paths marking important events in local Black, Irish and Women’s history. With an 81-year stay in Boston, the Braves left their mark on a fair share of city sites that would yield a similar walkable route for fans of the National Pastime. Let’s visit some of the stops on such a “fantasy” trail:

Braves Field

The most obvious and hallowed grounds for Boston Braves fans can found on the campus of Boston University at Nickerson Field. The university took over Braves Field after the Tribe headed to Milwaukee. Almost immediately, the school began to remove significant portions of the structure in order to make space for campus additions. Fortunately those plans included the preservation of a large portion of Braves Field’s right field pavilion for collegiate athletic event seating and the retrofitting of the ball club’s old administration building and main ballpark entry into the school’s police station. A large commemorative plaque on a pedestal has resided since 1988 in the courtyard in back of the latter edifice. Celebrating its 100th anniversary on August 18, 2015, Braves Field was Boston’s last new major league ballpark!

Among the structure’s many claims to fame, is the fact that the immortal Babe Ruth signed his last active player contract in this structure when he returned to Boston to play briefly for the Braves in 1935. Sadly, the Bambino’s stay was brief due to his deteriorating skills and a bitter disagreement with the club’s ownership as to his possible future role as manager/front office executive. Still, Braves Field can claim the distinction of having one of baseball’s greatest players appear on its diamond in the uniforms of four different ball clubs — the Red Sox (during the 1916 World Series), Yankees (when Boston’s “Blue Laws” prohibited Sunday games at neighboring Fenway Park), Braves and Dodgers (as a coach in 1938).

We’ll save a detailed discussion of Braves Field itself for another time. Suffice to say, the park affectionately known to its fans as the “Wigwam” (and the “Beehive” from 1936-40 when the club operated as the “Bees”), experienced many historic events including three World Series (twice borrowed by the neighboring Red Sox for a Fall Classic in 1915 and 1916) as well as Boston’s first All Star, Sunday and night ballgames. A portion of its left field pavilion served as the home of the Knot Hole Gang, membership of which provided inexpensive seating for area youngsters. On-field exploits of two of the Tribe’s pitchers in 1948 led a local sportswriter to pen a now legendary rhyme to the club’s lefty-righty duo, Warren Spahn and Johnny Sain. Over the years, the poem has mutated into “Spahn and Sain and Pray for Rain” but the original never included an invocation to the Deity for such relief but rather a hope for a couple of days of consecutive rainouts. In 1950, the Tribe broke the color line in the Hub when it added Sam Jethroe to the roster to patrol the Wigwam’s center field.

Braves Field also played a role in the early days of the National Football League. It was the first residence of today’s Washington Redskins, then also known as the “Boston Braves.” The pigskin club adopted its current controversial Redskins moniker after leaving the Wigwam for Fenway Park in 1933. The Boston Braves’ former public relations director, William H. “Billy” Sullivan, Jr., then the owner of a new-awarded American Football League franchise, used Nickerson/Braves Field in 1960 for the inaugural season of his Boston (now New England) Patriots.

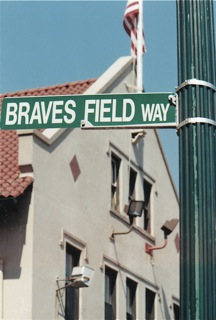

Gaffney Street & Braves Field Way

The street upon which the Braves’ former headquarters building resides has gone through three name changes. When James E. Gaffney, the Braves owner and building contractor of the ballpark, transformed the former Allston Golf Club course into a baseball diamond in 1915, he convinced city fathers to change this portion of the thoroughfare from Pleasant to Gaffney Street. That piece of Boston Braves history was extinguished many years later when Boston University petitioned the city to remove the Gaffney Street designation and rename the roadway “Harry Agganis Way” in honor of the late, famed university athlete and former Red Sox first baseman, who died tragically at a young age. The BBHA countered the school’s action by launching a successful campaign to name the untitled alley between the two streets (Gaffney/Agganis and Babcock Street) that border Braves/Nickerson Field, as “Braves Field Way.” That signage has been a frequent target of souvenir hunters but the BBHA persistently petitions the city for replacements whenever the street plaque goes missing!

Braves Field Streetcar Loop

Most folks in the past and the present have ventured to this site via a streetcar line that runs along Commonwealth Avenue. Today, one reaches the facility via the Green Line “B” Boston College route, disembarking on Commonwealth Avenue at the Babcock Street Station. During Braves Field days, a rail loop existed that deposited and picked up fans at a unique station within the ballpark’s confines. The transit authority deployed large, center-entrance trolleys capable of hauling 450 people at a time for this service. The packed cars that bore the nickname “people-eaters” or, less affectionately, “cattle cars,” entered on the Babcock Street side and exited onto Gaffney Street. The old tracks were paved over after the Braves left town but resurface periodically when the asphalt wears off on the Babcock Street side of the former National League diamond.

Case Athletic Center

Before leaving the area, one should proceed down to 285 Babcock Street to the university’s Case Athletic Center, a campus fitness and recreation facility. The Center sits on what used to be part of the home and left field covered grandstands of Braves Field. An archeological dig here might reveal remnants of the Braves dugout that sat on the third base side of the diamond and the home and visitor dressing rooms situated under those grandstands. On the Center’s lobby wall is a large framed set of three panoramic photographs that once adorned a Braves office in the administration building. The series of pictures document the building of the ballpark. Despite the fact that construction during that era still relied on the use of draft animals, as pictured in one of the photos, what was to be labeled the “world’s largest” concrete and steel ball ground was rapidly erected. Braves president Gaffney held a press conference on December 4, 1914 announcing the deal to buy the golf course land and build a new home for the Braves. On August 18 of the following year, the turnstiles spun as a huge crowd of 46,000 fans entered Braves Field for its inaugural game against the St. Louis Cardinals, won by the home team by a score of 3-1 .

Warren Spahn’s Diner

While in the vicinity, why not locate the spot of the ill-fated Warren Spahn’s Diner? With the motto, “The Best In Baseball — The Best In Food,” the restaurant was set for its debut on Opening Day 1953 to welcome hoards of hungry Braves Field patrons. Unfortunately, both Spahn and potential pre- and post game famished customers were in Milwaukee that April. Braves ownership shocked the team’s New England followers by abruptly pulling up stakes towards the end of spring training to relocate to Wisconsin. The restaurant, at 966 Commonwealth Avenue just opposite Babcock Street, is long gone. It transitioned into a Hayes Bickford diner and, ultimately, to a muffler shop.

Fenway Park

Our tour heads back to Kenmore Square in order to visit other landmarks of important Boston Braves history. While regarded as enemy territory by die-hard Boston Braves fans, Fenway Park rightfully belongs on the trail. During the last half of the 1914 season and while awaiting the opening of Braves Field in 1915, the Tribe borrowed their American League neighbor’s stadium to accommodate their fans. The Braves’ only “modern” World Championship was captured here. Mired in last place in mid-season, the Tribe’s last half surge into first place is one of baseball’s legendary accomplishments. In sweeping Connie Mack’s heralded Philadelphia Athletics in 1914, the “Miracle” Braves took the final two games of the Series at the Junior Circuit site on Jersey Street (now Yawkey Way). They played the 3-1 clincher on October 13 before an enthusiastic gathering of 34,365. Fenway Park would also serve as a home-away-from-home on other occasions, most notably in 1946 while the Braves awaited for the wet green paint on Braves Field grandstand seats to dry after an Opening Day fiasco at the Wigwam. Many fans left the 1946 inaugural game at the ballpark with stained clothing from newly painted seats that had not yet fully dried. From 1925-52, the Braves and Red Sox held a pre-season “City Championship” series that featured games alternating between their respective home fields.

Kenmore Square

Late on the rainy night of April 19, 1943, Braves manager Casey Stengel was struck by a taxi on a dark street in front of his residence hotel in Kenmore Square. His lower right leg was severely broken, requiring a lengthy stay at St. Elizabeth’s Hospital. The Braves skipper was forced to yield control of his team to coaches George Kelly and Bob Coleman for seven weeks. Boston Record sportswriter Dave Egan called the cabdriver “the man who did the most for Boston baseball in 1943.” The accident marked the beginning of the end of Stengel’s managerial tenure in Boston, which had begun in 1938. Club ownership, along with sportswriters and fans, had grown increasingly tired of Stengel’s eccentricities and his losing ways. The Old Professor was replaced the following season with Bob Coleman.

The Hotel Buckminster remains a commanding presence in the square. Situated at 645 Beacon Street, the building once housed the studios of WAAB-AM and WNAC-AM. The radio stations would consolidate operations to form the Yankee Network and would broadcast Braves and Red Sox home games and on-the-road recreations. An advertisement hanging in left field at Braves Field in 1939 urged ballpark patrons to “Follow The ‘Bees’ Over WAAB.” Later, broadcast operations moved a short distance around the corner to 21 Brookline Avenue.

In 1948, WNAC-TV televised the Braves-Indians World Series. Through heavy cable wires, television cameras set up in the rooftop press box section at Braves Field forwarded game action to a parabolic disc housed in a shed on the Wigwam’s roof. The disc provided a microwave relay to the studio off of Kenmore Square. The signal then was sent to the television station’s transmitter in Medford, MA and out over the air to existing TV sets. The Brookline Avenue site would become infamous for 2011’s “Chickengate” involving Red Sox pitchers Josh Beckett, John Lackey and John Lester. Rather than observing games from the dugout on their off days, the trio would relax in the clubhouse, consuming food picked up from a current street level tenant at 21 Brookline Avenue, Popeye’s Chicken & Biscuits.

The South End Grounds

Other ancient playing fields of the Braves should be included on our fantasy Tribe trek. The multi-turreted South End/Walpole Street Grounds no longer has any physical presence but a commemorative plaque was installed at the Ruggles MBTA Orange Line Station that was constructed on part of the old ballpark’s footprint. The dual reference of the stadium’s name reflects its presence in Boston’s South End and also the fact that its home plate bordered Walpole Street. The wooden structure was home to the ancestor Red Stockings upon their formation in 1871 and remained in use when the club became a charter member of the National League in 1876. Much of Boston’s early baseball glory occurred here as the team would claim 13 league championships at this home field. A second tier of seats was added in 1888 to address increased public demand. This addition gave the Grounds the distinction of being Boston’s first double-decked ballpark. Its small capacity (11,000 seats) and wooden structure would eventually lead to its demise. A fire that broke out during a game on May 15, 1894 not only incinerated the entire facility but also spread to neighboring properties within a 12 acre radius. The homeless ball club temporarily relocated to the Congress Street Grounds (a later stop on our tour) until a replacement was quickly built. By July 20, a new version of the South End Grounds opened for business. Due to the underinsurance of its predecessor, the ballpark was downsized from the original. Over the years that followed, ownership neglect of the facility resulted in fan dissatisfaction and put the club at a distinct competitive disadvantage with its newly-formed American League rival. When James E. Gaffney bought the team in 1912, he recognized that a new stadium for his Braves was an absolute necessity. While searching for a site, as previously mentioned he borrowed Fenway Park from the Red Sox during the latter half of the 1914 Miracle season and the subsequent post-season Fall Classic. The Braves also decamped at times at Fenway Park during 1915 until the gates swung open at Braves Field in August. In a move to tie the past to the present, the infield turf of the Grounds was stripped off and transplanted at Braves Field.

Northeastern University Campus

A piece of Northeastern University’s campus claims the remainder of the South End Grounds. That sprawling educational complex also stands on a former residence of the Red Sox — the Huntington Avenue Grounds, home of baseball’s first World Series. This site contains an elaborate tribute in its honor. In addition to a large plaque on the outer wall of the university’s Cabot Gym (with a World Series room inside), a 6’2” statue of Cy Young has been erected in a back mall. Young appears to be peering at his catcher and some 60 feet away resides a granite replica of home plate on the approximate spot of its Huntington Avenue Grounds’ ancestor. Since Young closed out his big league playing career and claimed the last four of his 511 victories with the 1911 Braves, his statue would be a legitimate stop on our fantasy tour.

Congress Street Grounds

As previously mentioned, the 1894 conflagration that consumed the South End Grounds forced the Braves (then referred to as the “Beaneaters”) to temporarily transfer their operations to the Congress Street Grounds, within a stone’s throw of Boston Harbor. This waterfront situated ballpark is an ancestor to the likes of Baltimore’s Camden Yards and San Francisco’s AT&T Park. The Grounds is without any present-day distinguishable marker. The best one can do is to walk along Congress Street, cross over the Fort Point Channel and head to the South Boston Waterfront area. Former warehouse buildings along 368-374 Congress Street stand on the approximate place of this hallowed ground. The area once was under consideration as a site for new homes of the Red Sox and Patriots.

The wooden doubled decked ballpark that featured two 75 foot towers housed a variety of Boston’s embryonic professional baseball teams from 1884 to 1894. Given its lack of a tenant in 1894, the Grounds provided a quick solution to the Beaneaters’ immediate need of a home turf. A distinguishing feature of this harbor-side diamond was the mere 250-foot distance to its left field boundary. During the Beaneaters’ short stay, 150-pound second baseman Bobby “Link” Lowe became the first player in National League history to clout four home runs in a game. The park’s closeness to Boston Harbor is responsible for the apocryphal tale that baseball’s longest home run was hit there. Supposedly, a ball swatted out of the park landed on an Australia-bound ship and traveled halfway around the globe! The Beaneaters’ last game here on June 20, 1894 was also the final professional ballgame for the Grounds.

The Paddock Building

One of the most obscure of Braves sites in Boston is the Paddock Building at 101 Tremont Street in the downtown area. This 11-story office building, across the street from the Granary Burial Ground, once housed the club’s headquarters. Brothers George and John Dovey operated the franchise out of an office in the Tremont Street structure from 1907-10. During this period, fans nicknamed the ball club the “Doves” after its ownership. John, who succeeded his sibling as president when George suddenly passed away in 1909, sold the team after the 1910 season. Perhaps the most notable event here took place during the regime of James E. Gaffney. It was from this location that Gaffney negotiated the purchase of the Allston Golf Club and subsequently informed Braves fans of his plans to transform that acreage into the new “Home of the Braves.”

The edifice housing the Braves administrative operations was named after Major Adino Paddock, whose Revolutionary War-era home originally stood on the corner of Bromfield and Tremont Streets. Paddock, a relative of one of the early settlers in Plymouth, was Boston’s first coach-maker and a man of substance. He was a respected pre-war captain of the city’s artillery and trained such future Revolutionary War notables as Brigadier General John Crane of Tea Party fame and General Henry Knox, the Secretary of War in Washington’s first cabinet. However, Paddock was an outspoken Tory and was forced to flee Boston when George Washington evacuated the city of British troops on March 17, 1776. His home was confiscated after he returned to England. Paddock’s earlier contributions to the development of Boston, however, were not forgotten and the developers of the office building chose to name the structure in his honor. Today, one of the building’s more noteworthy occupants is The Original Tremont Tearoom, self-described as “the world’s oldest and most reputable psychic institution.”

Horace Partridge Co.

The quest of sporting goods companies to be the “official” supplier of college and professional team paraphernalia is not a recent phenomenon. The Boston-based Horace Partridge Co. was a long-time purveyor of athletic equipment. It billed itself as the “Oldest Athletic Goods House in America.” The company secured the rights to dress the Boston Braves and proudly boasted of its license on the outfield walls of Braves Field season after season in the 1930s and 1940s. Its usual spot would be in the vicinity of left field where, in large lettering, the Partridge billboard would inform the ballpark’s denizens of its exclusive status as “Athletic Outfitter to the Braves.” Over those years, the Horace Partridge Company migrated from its headquarters at 34 Summer Street to 55 Franklin Street. Both addresses today border on Boston’s Downtown Crossing. Many now-defunct stores that operated in this once vibrant retail core of Boston along Washington and Summer Streets would sell advance reserved seat tickets to Braves games. Included among such remote ticket sale sources were the men’s stores in Filene’s, Jordan Marsh and Kennedy’s.

The Sports Museum of New England

The Sports Museum is located on the fifth and sixth levels of the TD Garden on Causeway Street in Boston. By the very nature of its title, it houses historic pieces and memorabilia relating to area professional and amateur sports. One memento in its possession holds a very special place in the hearts of hard core Boston Braves fans. It also answers the trivia question as to when the last time home plate was stolen at Braves Field.

Shortly after the shocking and heartbreaking word reached Boston in the spring of 1953 that the Braves would not be returning to Braves Field, a band of youths living near the park decided to pilfer home plate rather than to see it trucked to distant Milwaukee. The boys of Allston’s “Mountfort Street Gang” snuck into the Wigwam and, on that cold, bitter March day, dug up the plate by hand. Fearful of the repercussions that might follow from their act of thievery, members of the group hid the relic for the next 35 years. During ceremonies in 1988 in Boston honoring the 40th anniversary of the last Boston Braves National League pennant and the dedication of a commemorative Braves Field plaque at Nickerson Field, a member of the old gang presented the historic souvenir to the Sports Museum. Now on display at the Museum, a trip to the North Station arena’s museum would mark a fitting end to a day spent on the Boston Braves Historic Trail!

Bob Brady, a charter member of the Boston Braves Historical Association, is currently its president and newsletter editor. To read Bob’s informative newsletters for the Boston Braves Historical Association click here .

Great stories! I’m still a fanatic Braves fan (69th season). Will be in Atlanta for three games in May,as my wife and I do every year. —-I was a high school senior in 1953 when they moved. Cried like a baby! Every one else in my family is Red Sox fans,including four siblings ,four sons,and 13 grandchildren. Thank you,Bob. Thank you,BBHA. I still let Ryan and Shaugnessy have it now and then! Keep up the good work!

Spahn and Sain and pray for rain, is in my mind, still the greatest baseball headline ever written.

Thanks for bringing it to my old mind again Bob.

I grew up in Cambridge and was a member of the Knot Hole Gang. I hope I still have my autograph book with Sibby Sisti’s autograph, still hunting for it.

How great would that be!

We’re rooting for you!!

What was the name of the Boston Braves left-handed pitcher who left baseball to work as a plumber. He pitched with Spahn and Sain.