Anthony Richard Conigliaro was born in Revere MA, on January 7, 1945. It almost seemed that Tony Conigliaro was born to play with and star for the Boston Red Sox. Tony spent his earliest years in Revere, he learned to play baseball in East Boston, and the Conigliaro family moved to Swampscott on the north shore of Boston when he was a teenager.

Anthony Richard Conigliaro was born in Revere MA, on January 7, 1945. It almost seemed that Tony Conigliaro was born to play with and star for the Boston Red Sox. Tony spent his earliest years in Revere, he learned to play baseball in East Boston, and the Conigliaro family moved to Swampscott on the north shore of Boston when he was a teenager.

In his autobiography, Seeing it Through, Tony wrote, recalling his early days on the diamond, “I’d get up every day, put on my sneakers, ask my mother to tie the laces for me and run out the door to the ball field across the street from my house. That’s all I wanted to do.” He added, “I was there so much that the other mothers in the neighborhood began saying my mother wasn’t a very good one because she let me stay out there all that time.”

AUGUST 18, 1967

In early August 1967, Tony was batting .300, and like so many gifted athletes he made it look easy. But Tony’s younger brother Billy, who spent three seasons with the Boston Red Sox, two of them playing in the same outfield with his big brother, told me, “I don’t think people realized how hard Tony worked to get to the big leagues and how hard he worked to stay there. He would spend hours swinging a lead bat or squeezing a ball.”

Tony’s youngest brother, Richie, added, “The three of us would be watching television and I would look over and Tony would be using some of contraption that he put together to strengthen his wrists. He was always doing something to improve his batting skills. It’s hard to believe any ballplayer ever worked harder.”

Friday August 18, 1967, was a lovely summer day, the fourth consecutive day of full sun and daytime temperatures in the mid-80s. By game time the temperature would drop into the 70s, making it a perfect day to play and watch baseball. The crowd of just over 31,000 fans streamed into Fenway Park anticipating a great evening. Despite their disappointing play in August 1967, the Red Sox were still only three games out of first place and it had been a long time since a Red Sox team had been in contention for the pennant in mid-August.

Tony C had been in a bit of a slump lately with only one hit in his last six games. But after four seasons in the big leagues he realized that a six month season will have a number of personal ups and downs. Earlier in the season Tony had served two weeks with his Army Reserve unit at Camp Drum in upstate New York. The conflict in Vietnam had picked up and most major league clubs helped their young single players to sign up with a reserve unit rather than face the draft. Jim Lonborg and Rico Petrocelli had nearly been sent to Vietnam when their Seattle reserve unit was almost activated in 1964. Dalton Jones and pitcher Bill Landis were two other Red Sox players who had to juggle baseball and military service.

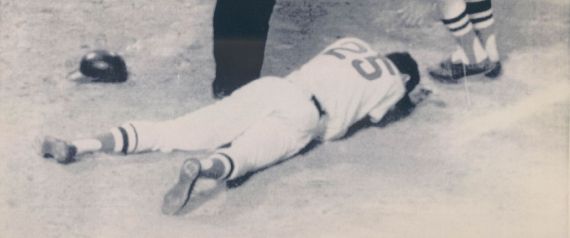

Tony C came to bat in the last of the fourth inning with two down, no one aboard and the score tied at 0-0. Hard-throwing right-handed pitcher Jack Hamilton, who was rumored to throw a spitball now and again, was on the mound for the California Angels. Hamilton reared up and whipped a fastball toward the plate. It zoomed across the intervening space right toward Tony’s head.

The youthful batter had always figured with his lion’s heart that he would instinctively know when to pull back and duck any ball by a fraction, no matter how hard it was thrown—even if directly at him. Still, the batter only has 0.4 of a second from the time the pitcher releases a 90-miles-per-hour pitch and the ball reaches the plate.

Tony did duck as he saw the ball headed for his chin. Still the ball as though radio-directed and fixed on his head came right at him. “It seemed to follow me in,” he would say later. “I know I didn’t freeze, I made a move to get out of the way.” As he threw up his hands to protect himself and began to turn away to his right, his helmet flew off.

Photo of Boston Red Sox outfielder Tony Conigliaro, on the ground after being beaned by California A’s Pitcher Jack Hamilton at Fenway Park in Boston. (Denver Post via Getty Images)

Tony never went to the plate thinking he was going to get hit or beaned. But he realized then that there was no way he was going to escape the impact of Hamilton’s pitched ball. The ball was only four feet from his head when he knew it was going to get him. Simultaneously, he knew it was going to hurt like hell because Hamilton had tossed it with enormous force.

Prostate on the playing field but still conscious, Tony had lost sight temporarily in both eyes. As his teammates rushed toward him, led by Rico Petrocelli who had been in the on-deck circle and Mike Ryan, Tony’s best friend and roommate on the road, the right fielder laid without moving.

Rico knelt and gently shook his shoulders. “Tony, Tony, are you all right? It’s okay. You’re gonna be okay.” More Red Sox gathered. The club trainer, Buddy LeRoux, rolled Tony over. When he didn’t move, they all began to fear the worst. Rico almost got sick looking at his crushed cheek and swollen shut eye. Rico told me later, “When I first got to Tony, I thought he was dead. He was just lying there motionless.”

RECOVERY

Tony was rushed on the stretcher into the clubhouse where LeRoux placed an ice pack against his head. Dr. Thomas M. Tierney, the team’s physician, was in the stands when Tony went down and hurried to his side in the clubhouse. The physician was an old friend of the Conigliaro family but had no time then for small talk. He ordered an ambulance to be called and began testing Tony’s blood pressure and reflexes.

Tony was then rushed by ambulance to Sancta Maria Hospital in Cambridge where he was examined by Dr. Joseph Dorsey, a neurosurgeon. The doctor would say later that Tony had suffered a fractured cheekbone, a scalp contusion and that it was too soon to determine the extent of the injury to his left eye. He acknowledged that Tony might have been killed if the ball had hit him an inch higher.

No matter what some people might think about his pitch, Jack Hamilton demonstrated his class by being among the first arrivals at the hospital in the morning to try to visit Tony. Except for his family, Tom Yawkey and his great pal Mike Ryan who sneaked in, Tony was forbidden visitors but was apprised that Hamilton had attempted to see him.

Tony was a big fan of Yawkey and was surprised when he was awoken the next morning by a voice saying, “Wake up, Tony. It’s me, Tom Yawkey.” The Red Sox owner had always been kind and patient with his young outfielder and often listened to his personal problems. “Now as busy as he was, he was sitting in my room, holding my hand, and telling me not to worry about anything.”

This game against the Angels on August 18 was the last one for Tony Conigliaro in 1967. Vision problems with his left eye ruled out any possibility of his returning to the Red Sox. The blind spot in the eye just wouldn’t get any better. Moreover, he still had a lot of swelling in and around the eye and he was told that “your distant vision is so bad that it might be dangerous for you to play anymore this year. You just can’t be ready to play in the World Series if the Red Sox make it.”

Tony, of course, was crushed by the news. He was always hopeful that the eye would improve and he’d get back with the team to make a bigger contribution to the race for the pennant. He went back to his apartment near Fenway and cried. “For the first time I realized how much I loved it all . . . I missed the games, the competition, especially now with the ball club fighting for the pennant. There was nothing else I wanted to do except play baseball.”

Tony did drop by the Red Sox clubhouse a number of times following his injury and even sat on the bench in uniform on a few occasions. His teammates went out of their way to make him feel welcome but Tony was never truly comfortable because he wasn’t contributing. He was in the Red Sox clubhouse after their win on the last day of the season and he could be seen sobbing quietly with owner Tom Yawkey’s arm around him to provide comfort.

HOMETOWN BOY MAKES GOOD

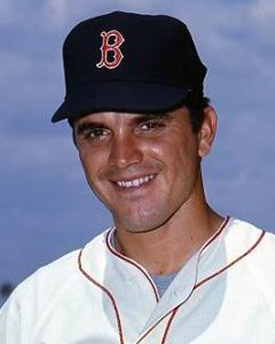

Although he was to be out of baseball until 1969, Tony had already chalked up a commendable record in the game, beginning with 1963 when he hit .363 with Wellsville and was named MVP of the New York-Penn League. Tony moved up to the Red Sox in 1964 at the call of manager Johnny Pesky.

When I asked Johnny if he had considered sending Tony down for more seasoning in the minor leagues after his outstanding performance in spring training, Pesky said, “Not for a minute. And if I hadn’t brought him back to Boston the fans would have killed me!”

As a nineteen-year-old rookie, Tony hit .290 with twenty-four home runs—the most by a teenager in baseball history. On June 3 of that year, he hit a bases-loaded homer off Dan Osinski then of the Angels, and later a teammate of Tony’s on the 1967 Red Sox, to earn the distinction of being the youngest player in the majors ever to hit a grand slam. In 1965, Tony led the American League in home runs with thirty-two; at twenty years of age, he was the youngest player ever to lead the league in four-baggers. All told, he was at bat 521 times and got 140 hits for 82 RBI.

Johnny Pesky was fired as manager that year and replaced by Billy Herman, a man that Tony claimed was on “different wavelengths” than him. Tony was to say that 1966 was the year that “a lot of things happened to me that pretty much established my baseball image: I proved myself as a home-run hitter. I got myself into a lot of hot water with the baseball writers. I couldn’t get along with Billy Herman.”

Tony came to discover that his candid and outspoken views did not play well in the papers or in the front office. For the most part, he was a guileless local boy who spoke his mind. He never claimed that he was a rocket scientist and it took him a while to realize he was living in a fish bowl. Before he caught on he had made almost as many trips to general manager Dick O’Connell’s office as he had made to the principal’s office at St. Mary’s of Lynn.

Tony managed, however, to achieve another exemplary year in 1966 by hitting .265 and rapping out 28 homers. He was at bat 558 times and got 148 hits with 93 RBI. While Tony seldom had a good word for Williams, he did note after the “Impossible Dream” year that the manager “did an incredible job, taking a ball club that finished ninth two years straight and managing it to a pennant. If Williams ever was likable, it was in 1967 because he was up there fighting all the time and personalities never were a factor. We were a happy club and showed up every day believing we were going to win.”

Until he was hit by Jack Hamilton’s pitch, Tony was enjoying a 20-homer season and batting .287. He had been up to the plate 349 times and collected an even 100 hits and 67 RBI. He was obviously a young man on a path to a likely induction into baseball’s Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York.

COMEBACK FOR THE AGES

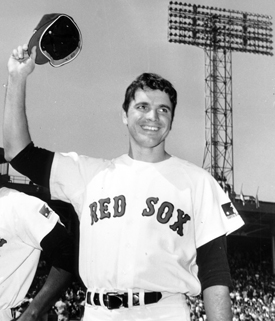

After missing the entire 1968 season, Tony was back with his beloved Red Sox for opening day 1969 against the Orioles in Baltimore. Everybody thought that Jack Hamilton’s pitch had finished him, but he was determined to prove everyone wrong. He did it by hitting a tenth inning homer that tied up the game which the Red Sox eventually won 5-4.

All in all, he came back big in 1969, slamming out twenty homers and winning the Hutch Award for being the player “who best exemplified the fighting spirit and burning desire of the late (pitcher and manager) Fred Hutchinson.” He was also voted Comeback Player of the Year.

The next year, 1970, was even more of a banner year for Tony as he batted a career-high thirty-six homers and hammered out 116 RBI. Incredibly, the Red Sox traded him in October to the California Angels partly because the Red Sox didn’t want Tony and his younger brother, Billy, who had joined the Red Sox, to be playing on the same team.

Red Sox general manager Dick O’Connell, perhaps Tony’s best front office friend on the ball club over the years, said, “Frankly, we considered Billy a better ballplayer under the circumstances.” For serious Red Sox fans the move was akin to trading the U.S.S. Constitution to Baltimore in return for the U.S.S. Constellation.

The Red Sox apparently made the right decision because Tony’s eyesight began to fail when he went to the Angels and he only played seventy-four games total for them in 1971 before calling a middle-of-the-night news conference in June to announce his retirement. Four years later in 1975, he asked the Red Sox to invite him to spring training where he made the Red Sox as a designated hitter. He played in twenty-one games that season but hit only two homers and .123 and finally decided to call it quits.

It should be remembered, however, that Tony had burned up the Grapefruit League and astounded everyone with his hitting prowess. This may have been one of the most amazing feats in the history of baseball. The man had been out of baseball for nearly three and one-half years and there is some evidence to suggest that he was hitting literally from memory.

Billy and Richie Conigliaro were continually throwing him batting practice during the years he was out of the game. “He clearly had a blind spot in his left eye,” Billy told me. “I know that because if I threw the ball to a certain spot he would miss it entirely. I could tell that he hadn’t really seen the ball.”

Red Sox infielder and pinch hitter extraordinaire, Dalton Jones, came up to the Red Sox with Tony in 1964 and they were good friends during their six years together on the team. I asked Dalton what he thought Tony C might have achieved if he had never been injured, and he said, “First he would have hit over 600 home runs and been elected to the Hall of Fame. Then he would have gone to Hollywood and become a famous movie star. After that he would have come back home and been elected Governor of Massachusetts.” And Dalton added, smiling, “And I’m only half-kidding!”

GONE TOO SOON

The years passed and Tony got into sports broadcasting as an announcer and a color man. After being interviewed by the Red Sox for a broadcasting job, Tony was being driven to Boston’s Logan International Airport on January 9, 1982, by his brother Billy when he suffered a massive heart attack. The vicious blow disabled him completely, requiring his mother, Teresa, and his brothers, Billy and Richie, as well as nurses, to provide constant care.

During the week of February 19, 1990, Tony C, the local boy who shone as a star outfielder for the Red Sox from 1964 through 1975, was admitted to a hospital in Salem, Massachusetts. He developed a lung infection and kidney failure and died peacefully in his sleep at 4:30 p.m., Saturday, February 24, 1990. He was forty-five years old.

Tony Conigliaro was born in Revere, Massachusetts, in 1945. He played his first baseball on East Boston sandlots and then he was a three-letter athlete at St. Mary’s in Lynn. After only a year in the minors, he was called up to the Red Sox. He made his debut with the Bostonian’s at the age of nineteen. The date was April 16, 1964, and the site was Yankee Stadium. He hit a home run in his first at-bat in Fenway Park the next day.

Johnny Pesky, who was associated with the Red Sox for almost 70 years, called the death of Tony Conigliaro “so sad and a damn shame. He was the best young hitter I ever saw other than Ted Williams. He was six foot, three inches tall, and weighed about 190 pounds. A good-looking player with a lot of ability. A great hustler who could do a lot of things— run, hit and throw. Ted Williams always thought he could be another Joe DiMaggio. Remember, he was the youngest guy to hit 100 home runs in the American League.”

On a cold, crisp winter morning in Revere, Tony’s funeral mass was celebrated at St. Anthony’s Church, a big and truly beautiful edifice, the Yankee Stadiums of churches. He had been baptized, taken his first Communion and confirmed in the same church. Bishop John Mulcahy told the nearly 1,000 mourners, “Tony did what God wanted him to do. God gives special talents to many people, and it’s obvious that He gave Tony a singular, unique talent of being able to hit a baseball. God gives those talents to people so they can make other people happy.” The Reverend Dominic Menna went on to tell the congregation, “Tony taught his fans that a runner who looks back never wins the race and he looked ahead to a successful career and did all he could to make it a success.”

It is hard to believe that Tony C has been gone for over 25 years now. But for as long as New England kids play baseball with snow shoveled to the sidelines, and dream of someday starring for the Boston Red Sox, the spirit of Tony C will always be among us.

********************************************************************************************

This feature has been excerpted from the recently released The Impossible Dream 1967 Red Sox: Birth of Red Sox Nation To purchase a copy signed and inscribed as you direct by author Herb Crehan go to “Books.“

Tony C. was born January 7th, 1945, I followed his every moment in baseball. Belonged to his fan club and even met him when we had a party for him one Sunday after a loss. He arrived and said, “Guys if I look a little down, it is because I don’t like celebrating after we loss today” To which we all said, We still love you, your the best.

We took pictures with him and everyone was so happy he did show up that Sunday night. The year had to be 1966. He had a gray corvette and the President asked if she could have a ride to Rt. 24 and her parents would follow. I of course envied her so much, me and my 2 friends followed them to the Rt. 24 exit and then he was heading toward Boston(by the way he warned her she would feel all the bumps but if she wanted the ride it was ok with him) As he was ahead of us, me in my poot poot Mustang ( I had a bad muffler) pulled up alone side of him, he knew we were the same people at the party, he could have blown my doors off but he stayed at the same paste with me and naturally we all waved and then our exit to go home to Fall River was coming up and he waved again and we turned and he went off back to Boston. Also on a side note, their was beer at the party cuz there were some older people there. I was a soda person, he asked for a glass of milk, and as the host to please remove the beer cans from in front of him(he said,”I don’t want people getting the wrong impression cuz I know you guys all have your cameras) I did get a picture or two and yes 1 was taken before the cans were removed. But he never drank beer only milk. He was the nicest person to us. Then they took questions from us, and me beet red asked,”Who is the best player on the Red Sox, catching myself I said,”you are of course” but who do you like and he said Moe Vaughn, hoped I spelled that right. He just was so natural and so nice to everyone and letting us follow him until we exited was so cool. We saw him at games after that and he remembered us and always came over and said hi, or just waved. I have had my crushes on many a boy, but with Tony C. it was a dream just to see him and when our Fan Club President had a contest to figure out how many homeruns he was going to hit one year, I calculated and did all kinds of figures to come up with 32. Yes that year he did hit 32 home runs. A autograph photo was sent to me and I was in LaLa Land. Always will remember you Tony. Just thought he would like to know his birth date is the 7th of January. RIP Tony C. love you forever.

I knew Tony for many years and, on occasion, he and a few of us would drop down to a nightclub in Revere called the Flamingo for a drink. The place was unique in that each table had a telephone and guys (and girls) could phone a table and ask for a dance. naturally Tony was inundated with calls, most of which he had to decline (but did so respectfully).

We lost touch when I got married but, when he came back to Boston (Providence) and bought a nightclub, some of the old guys came down to hang out with him. Through it all Tony was always the same guy and always a real friend.

I’ve been involved, through the years, in both efforts to have his #25 retired in Fenway Park…all to no avail. His brother Richie recently told me there’s a new attempt about to surface. Hope THIS time it finally happens.

The Boston Fans he loved so dearly all deserve the opportunity to have a lasting remembrance of our beloved TONY CONIGLIARO.

I hope, when the time comes, the Red Sox ownership will do the right thing…both for Tony and the fans…..God Bless and remember……

Got to know Tony in’63 in Wellsville NY (NY-Penn league). Became good friends. Went to Boston in ’64 and got to some 30 home games on family tickets. We ran around after the games (sometimes had to run away from avid female autograph seekers). Had dinner at his parents’ house a few times. Needless to say, great food. I followed his career closely after that. The last time I saw him was in’75 at his restaurant in Nahant. I too was devastated by his injury and, of course, his passing. I will never forget him. He will always be in my Hall of Fame.

I watched the Red Sox in 1967 with my husband. We saw the game when Tony got hit. I liked the song “Where have all the flowers gone”. I’m still a Red Sox fan and looking forward for baseball season

Jim Tuberosa and others:

Tony’s spirit and determination is honored every year with the Tony C Award, given annually at the Baseball Writer’s Banquet in January to a major league player who best exemplifies the courage Tony demonstrated.

I spearheaded that campaign to have #25 retired, and this came about after I contacted the presidents of both leagues, the Commissioner of Baseball, the head of the Baseball Writers Association of America, Mrs Yawkey, Dick Bresciani, Ken Coleman, various teammates of Tony (Rico, Mike Andrew’s among them), and the Conigliaro family. My idea was to institute an annual award bearing his name.

I was then contacted by Richie Conigliaro to coordinate the efforts of several groups to work toward getting Tony’s 25 retired, and I wholeheartedly devoted months to that goal, eventually meeting with then- Red Sox VP Public Relations Bresciani at Fenway and presenting 25,000 signatures garnered all over New England to the Red Sox letting them know this is what the fans want. Jim, I remember speaking to you when this was happening.

The club denied this because Tony did not meet the qualifications, namely having played 10 years for the Sox and being in the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Instead, they coincidentally instituted the Tony C Award, which I suggested days after Tony died, and had an on-field ceremony announcing it. Tony’s brothers, his teammates Rico and Andrews,

the who’s who of Baseball all there, and me watching from the stands.

No mention then or when they presented the first award that January that the idea came from a devoted fan, though I will say they named me to the panel to determine the recipient of the Award….but after two years, I never did receive correspondence regarding voting anymore.

I loved Tony C and I hope that there will be more press regarding this award so young fans will learn about the extraordinary spirit and determination that defined this man. He personified “I can do this!” And that is a noble trait to emulate.

Karen Parente

karen714@verizon.net

The fact that number 25 is not retired with all the Red Sox greats is a crime.

He was, and always will be my favorite Red Sox player!

It’s a shame they haven’t honored him by retiring his number.

Tony C was my all time favorite,loved to watch him play.I wish they would retire his number 25.

tony c was a classmate of my uncle Richard ross at ST Mary’s .He played ball with us now and then at the sagamore ST playground . IN Lynn. When he was up it was ok to put outfielders on amity ST. We all hard one those $1 rubber balls. it would look paper thin when he hit it. some times it exploded too. 3 or 4 times he loaded up a bus with kids from the confessional church on broad ST IN LYNN. TO GO TO A GAME.

retire his number