Veteran baseball writer Dick Trust reminds us that there was a day when a teenage fan could form a relationship with a major league player and even be invited into the clubhouse!

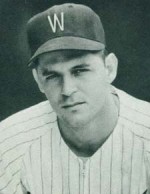

Pedro Ramos was a cigar-smoking Cuban right-handed pitcher with the Washington Senators when I met him in early summer 1959. After I got his autograph outside the Hotel Kenmore, it was close to the time when ballplayers had to be at the park, in the clubhouse, and ready for batting and fielding practice. Pitchers light-tossed and amusedly shagged fly balls.

Seeing as though Ramos was the last player leaving the hotel – he told me everyone else was gone and he had to hustle – I kept walking with him to the ball park. He doesn’t mind my company, I thought. What was my name? How old was I? What school did I go to? What grade was I in? Did I play baseball? Who was my favorite player? Pedro made the short distance from Kenmore Square to Fenway Park go quickly with his questions in an exotic (to me) Spanish accent and my little answers in a mid-teen Boston accent.

When we arrived at Fenway, and it was time for Pedro to go through the gate and into the park, a curious – and wonderful – thing happened: He asked me if I had a ticket to the game. I did not. He then looked at the security guard and told him that I was with him. The guard waved me in and a soaring feeling came over me. Pedro Ramos just brought me into the ball park. This is incredible.

There was more. We walked through the dark, musty corridor and soon we were

outside the visitors’ club-house, a place I usually had approached after games

with anxiety, seeking my precious autographs while hoping a cop wouldn’t spot

me and give me the old heave-ho.

“Wanna come in?” Pedro asked me.

“In the clubhouse? With you?” I said.

“Sure. You can stay for a little while.”

“Sure.”

In we went, to the sacred clubhouse of the Washington Senators. Pedro left my side and went to change into his uniform. I stood there and took in the scene, players getting into their gray Washington uniforms, one on a table, getting a massage. I recognized many of the Senators parading past: Here was Bob Allison, there was big Jim Lemon. Harmon Killebrew. Camilo Pascual. Chuck Stobbs. The Washington Senators, of whom it was jokingly said: “Washington, first in war, first in peace, last in the American League.” Sadly, that was so, but it mattered not to me, at 15, in a place most kids only dreamed of visiting.

I did not ask for autographs. I had most of them already in autograph books, on photos or on index cards. I’m not gonna bother anybody, I thought.

Pedro soon informed me that my “little while” was up and it was time for me to leave the clubhouse. I thanked him for what he did, wished him luck in the game (he wasn’t pitching that day) and I headed out the door, still soaring.

There was still more to come, but I didn’t know it yet as I caught up with my autograph buddies in the left-field grandstand, hoping to get a batting practice ball, even it was grass-stained, or nicked or far from game-perfect in some other way. In my time (a 5-year-span, 1956-60) collecting baseballs in batting practice for autograph purposes, I managed to retrieve 22 baseballs in all manner of conditions. I never actually caught one on the fly – luckily, I always believed, because they came at you with such speed and force. I got them all after they had landed with a familiar crash against wooden seats and rattled and rolled before I’d win the race, zigging here, zagging there, and barely snatching them from the grasps of my cohorts.

Occasionally a ball took one or more high bounces before I was able to latch onto it on its downward path.

I was the envy of my buddies that day as I recounted my pre-batting practice adventure in the clubhouse with Pedro Ramos. As BP was ending, I caught sight of Pedro as he headed in toward the visitors’ dugout on the third-base side. I rushed down through the box seats and called out, “Hey, Pedro.” He stopped, looked up and said, “Hi.” Then he said, “Wait here a second.” Puzzled, but filled with anticipation, I waited by the little wall that separated seats from field.

A minute or two later, Pedro Ramos emerged from the dugout, holding a little square box. He opened it and handed me the contents – a brand-new American League baseball, glossy and even better than game-perfect because it didn’t have that mud from a Delaware river that is rubbed on baseballs before games to keep them from slipping out of a pitcher’s throwing hand.

I was stunned, but I had one request after thanking Pedro and asking him to sign the ball: Could he get the whole Senators team to autograph the ball? Without hesitation he agreed. He said, “See me here after the game.” I rushed to the area of the dugout after the game and Pedro showed up as he promised with the shiny, new baseball filled with autographs.

I may have been the envy of all who all who witnessed that little exchange, but the one I really wanted to impress was my father, who endured the daily drudgery of hard, low-paying work in a shoe-trim factory. When I was 16, and it was time for my first summer job, my dad managed to get me work there – for a dollar an hour, minimum wage back then.

I was ready to quit after one day, but my dad, who tried hard to get the job for me, asked if I would stay at least through the next payroll day, which was the following Tuesday. Reluctantly I agreed. After seven business days, I was gone from that tedious, nowhere job that, for many of the adults who worked there full-time, was necessary to pay the bills. What did I know about bills at that age? What I hated most was having had to get up at 5:15 a.m. with my dad and the monotony of making hundreds of shoe buttons on a metal press.

My father’s job, more varied than mine but no more interesting, provided sole support for our family – mom, dad, my sister (before she married at age 20) and me. He didn’t make much more than I was paid, but with rent $35 to $40 a month for our apartment in an orange-brick three-decker in Roxbury, Massachusetts, and no automobile to maintain – we took public transportation everywhere, except when friends or family came to take us out for a Sunday ride – he didn’t need big bucks to make ends meet.

My dad worked hard for most of his life. He told me he got his first job, hawking newspapers, when he was 12. He smoked since he was 13 or 14. He grew up fast, married my mother in Depression-days 1932 – they were both 30 – and raised two kids, my older (by 8½ years) sister and me.

He was a baseball fan forever, it seemed. He knew all the early-20th century players, had seen many of them play, and passed that knowledge down to me. The names Cy Young and Tris Speaker and Smoky Joe Wood were as familiar to me as were Ted Williams, Mickey Mantle and Yogi Berra. He saw The Babe play, he saw Ty Cobb, Lefty Grove, Walter Johnson, Rabbit Maranville, Jimmie Foxx.

He went to big league baseball’s longest game ever (in innings), the Boston Braves-Brooklyn Robins 1920 epic at Braves Field that required 26 innings and ended in a 1-1 tie because of darkness after a tidy 3 hours and 50 minutes. Both starting pitchers – Boston’s Joe Oeschger and Brooklyn’s Leon Cadore – went the distance! In 1948 he sat in the bleachers at Fenway Park as the Cleveland Indians beat the Red Sox in a one-game playoff, thereby killing the chance of a subway World Series with the Boston Braves.

My dad took me to my first big league game – actually a doubleheader – in 1949, with the Philadelphia Phillies the opponents at Braves Field. Later that same season, he brought me to a Braves-St. Louis Cardinals twin bill. My favorite Brave was Earl Torgeson, the bespectacled first baseman of the Braves who wore No. 9 – as did my all-time favorite-to-come, Ted Williams.

I attended my first game at Fenway Park in 1951. We sat in the right-center field bleachers and I remember observing that Sox shortstop Vern Stephens was bald when he momentarily took his cap off, and my dad pointing out that center fielder Dom DiMaggio was known as “The Little Professor” because he was smallish, wore glasses, was very bright and, for good measure, played his position with skill and speed and batted a solid .298 lifetime.

A generation later, in 1975, I was well into my career as a sports writer for The Patriot Ledger of Quincy, Mass., and covering the Red Sox frequently. On an off day (for me), I took my dad to a Sox-Twins game at Friendly Fenway. My dad then was in the advanced stages of a cancer that would take him from us, at age 73, in October of that year – but not until the World Series was over and Carlton Fisk had waved his Game 6 fly ball fair for the winning, 12th-inning home run. (We won’t talk about Game 7.)

I wanted my dad to meet at least one player the day I took him in. While watching the tail end of batting practice from a field box, Minnesota rookie outfielder Dan Ford strolled by. I called him over, introduced myself and then had him meet my dad. They shook hands and my dad’s face, so thinned by illness, was full with a glow. A small moment, perhaps, for Dan Ford, but it made my dad’s day. It was his last trip to a ball game. We didn’t ask Ford for his autograph. I didn’t take a picture of him with my dad. It’s the memory of the moment I still cherish.

Four years earlier, at the 1971 Hall of Fame induction ceremonies in Cooperstown, New York, my dad had met, and I photographed him with, stars of his era: Lefty Grove, Lefty Gomez, Rube Marquard, Luke Appling, Casey (and wife Edna) Stengel, and a couple from “my” era, Sandy Koufax and commissioner Bowie Kuhn. Looking at those photos now brings back fond memories.

One memory I won’t have is taking a ballplayer – a major league baseball player – home to have dinner with my family and me. I thought many times of inviting Pedro Ramos home for dinner. I figured he ate hotel and restaurant food so often that he might appreciate a home-cooked meal prepared by my mom. We would have to take a trolley, a rapid transit train and a bus to get back to my house, but, I imagined, Pedro wouldn’t mind. And, boy, would that impress my dad and everyone else I’d be telling. Guess who had dinner with US last night?

Well, I never did muster up the courage to invite Pedro. I don’t know why I didn’t. Maybe I did too much thinking and feared that he would say no. But what if he said yes?

Dick Trust’s new book, “Ted Williams and Friends: 1960 – 2002,” a photographic account, with text, of Ted’s post-playing career, has been released by Arcadia Publishing. To order a copy go to http://www.arcadiapublishing.com/9781467122948/Ted-Williams-and-Friends-1960-2002.

Or you may email the author directly at: rtrust68@comcast.net.

Great memories, Dick!