Spring training is a time of renewal for players and fans. But spring training in Sarasota, Florida, in 1946, was more than a renewal; it was a reunion of Red Sox players who had been away for as long as three seasons while they served their country during World War II. The 1946 Boston Red Sox spring training roster included 28 players who had spent the 1945 season in the U.S. armed service.

The late Johnny Pesky remembered greeting his former teammates in February 1946. “It was great to see all my old friends and teammates. I had seen Ted [Williams] from time-to-time during the war, but I hadn’t seen Dom [DiMaggio] in over three years, and I had lost track of a lot of guys like Eddie Pellagrini and Charley Wagner.”

More than 300 players with major league experience, and over 4,000 minor league players, served in the U.S. military during World War II. Sadly, 131 professional baseball players, including former major leaguers Elder Gedeon and Harry O’Neill, gave their lives in service to their country.

Johnny Pesky captured the mood of spring training in 1946, when he said, “We had all made it back. A lot of people didn’t. We were together again, and we were playing baseball.”

WARTIME BASEBALL

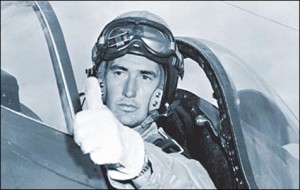

Ted Williams and Johnny Pesky enlisted in the Navy’s V5 program and reported for active duty two weeks after the end of the 1942 season. Dom DiMaggio and Eddie Pellagrini joined the Navy as well. Bobby Doerr was exempt from service due to a punctured ear drum but he joined the Army in 1944.

Former Red Sox players were scattered all over the world serving their country, but Pesky recalls that they were not forgotten. “Barbara Tyler, who was Eddie Collins’ [Red Sox general manager] secretary, put together a four-page newsletter and sent it to all of us every few months. And Helen Robinson [long-time Red Sox employee] knit socks for a lot of us. It meant a lot to know we were remembered,” Johnny emphasized.

Shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, baseball commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis wrote to President Roosevelt, asking whether major league baseball should be suspended during this time of national emergency. President Roosevelt answered that he felt it would be good for the nation’s morale if baseball continued. The president also stressed that able-bodied players should not be exempt from military service.

By 1943 the majority of major leaguers had enlisted in the armed forces. Major league teams were staffed by players with physical conditions disqualifying them from military service, younger players, and older players past their prime. Pete Gray, who had lost his right arm in a childhood accident, played 77 games in the outfield for the St. Louis Browns in 1945. Joe Nuxhall pitched for the Cincinnati Reds as a fifteen year-old in 1944. Babe Herman, who had been out of baseball since 1937, returned from retirement and played in 37 games for the 1945 Brooklyn Dodgers.

As World War II wound to a close in 1945, U.S. military personnel around the world were being discharged and beginning the transition to civilian life. Johnny Pesky was stationed in Honolulu, Hawaii, when his discharge orders came through. Bobby Doerr, who had been serving in the U.S. Army at Camp Roberts in California, sent a telegram to the Red Sox in late 1945, informing the club that he had been discharged and would report to spring training in February 1946. For Pesky, Doerr, and 26 of their Red Sox teammates, the transition to civilian life would begin in Sarasota, Florida.

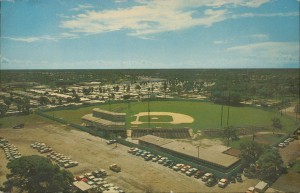

SLEEPY SARASOTA

In 1946 Sarasota, Florida, was a sleepy village of about 5,000 residents. The Red Sox had trained there from 1933 to 1942, but wartime travel restrictions forced them to train at Tufts University in 1943, Baltimore, Maryland, the following year, and in Pleasantville, New Jersey, before the 1945 season.

Bobby Doerr remembers Sarasota as a wonderful place to bring his family for spring training. “There wasn’t much to see once you got out of the downtown area,” Bobby recalls. “My wife Monica and I had a nice apartment that wasn’t far from the ballpark. Sarasota was the winter headquarters for the Ringling Brothers, Barnum and Bailey Circus, and the performers would come to our games, and Monica and I would take our young son Donald to see the circus.”

There was an air of optimism at the 1946 Boston Red Sox spring training camp. With the return of Williams, Doerr, Pesky, and Dom DiMaggio, plus the off-season acquisition of slugger Rudy York, the offense appeared potent. The return of pitchers Tex Hughson, Mickey Harris, and Joe Dobson, coupled with emergence of young Boo Ferris in 1945, provided a strong pitching nucleus. The big question was: How long would it take players who had missed up to three seasons to return to form?

Chicago White Sox manager Jimmy Dykes, who had been an active player after World War I, predicted it would take a full season for the veterans to regain their skills. But one session by Ted Williams in the batting cage convinced Johnny Pesky that it wouldn’t take the Splendid Splinter that long. “That beautiful swing was still there,” Johnny says. “His timing was a little off, he had missed three full seasons after all, but he still had that wonderful stroke.”

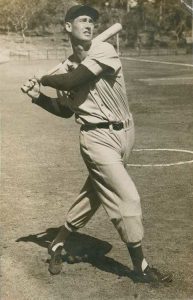

DAVE “BOO” FERRISS

Dave “Boo” Ferriss, from Shaw, Mississippi, had taken the American League by storm during the 1945 season. Ferriss had been drafted into the Armed Service in 1942, but in early 1945 a chronic asthmatic condition worsened and he was hospitalized for over six weeks. The Army doctors finally concluded that his condition would not improve, and he received his honorable discharge.

![ferrisp[1]](https://bostonbaseballhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/ferrisp1-224x300.jpg)

Given a chance to pitch at the major league level, the 23-year-old Ferriss made the most of it. The 6’2” rookie right-hander won 21 games and was named to the American League All-Star team. His outstanding major league debut included 26 complete games, and his 22 inning scoreless streak to begin his career established a new American League record.

Before spring training began, Boston newspapers were filled with stories suggesting that Ferriss wouldn’t be able to handle the great hitters returning in 1946. But Boo didn’t share their pessimism. “I had a lot of faith in my pitching ability,” he recalls. “And I knew I was going to have a better team behind me. That gave me a lot of confidence.”

Boo’s confidence received an additional boost after pitching to Ted Williams in batting practice early in spring training. “Ted had told the writers that he wanted to see what he could do against me,” Boo says. “When he would get in the batting cage everyone would stop and watch. I wasn’t even throwing my best stuff to him, just three-quarters speed, trying to throw strikes.

“When Ted stepped out of the cage the writers peppered him with questions. ‘Don’t worry about that guy,’ Ted told them. ‘He’s for real. He can pitch.’ That’s when I was sure I would be fine.”

One of Boo’s strongest memories of spring training in 1946 is the Red Sox trip to Havana, Cuba, to play two exhibition games against the Washington Senators. “We traveled everywhere by train in those days, and I can remember standing on the tarmac at the airport in Sarasota, getting ready to board a Pan American Clipper, and thinking what a big deal it was.

“And I’ll never forget our stay in Havana,” Boo says. “Bobby Doerr was my roommate and we woke up at about 2 AM to a big commotion in the hallway. We peeked out, saw the police running around and went back to bed to try to get some sleep. The next day we found out someone had been murdered a couple of rooms down from us. That’s one trip I will never forget,” he emphasizes.

WHAT’S THE MATTER WITH THE RED SOX?

In a sure sign that things were returning to normal, controversy visited the Red Sox spring training camp in March. The controversy came in the form of an article in the Saturday Evening Post entitled, “What’s the Matter with the Red Sox?” The article, written by veteran Boston sportswriter Harold Kaese, bemoaned the fact that the team hadn’t won an American League pennant in 28 years, and questioned whether Joe Cronin’s managerial skills were up to the task.

The controversy was short-lived since players and baseball writers alike agreed the problem was a shortage of quality pitchers and that wasn’t Cronin’s fault. And there was general agreement that the team’s biggest problem was playing in the same league as the powerful New York Yankees.

A lighter controversy arose when a number of unnamed Red Sox players told writers they would rather “eat out” than take their meals at the Hotel Sarasota Terrace, the team’s spring headquarters. The hotel responded by paying to have their menu printed in a Boston sports weekly. With a five course prime rib dinner available at $2, readers back in Boston probably weren’t overly sympathetic.

ROUNDING INTO FORM

By late March, the 1946 Red Sox were coming together as a team. Veteran starting pitchers Tex Hughson, Mickey Harris, and Joe Dobson had pitched well and Boo Ferriss, who had three complete game wins that spring, had shown that he could pitch against the returning stars. The team was still looking for a third baseman and a regular right fielder, but the rest of the starting lineup was set.

Manager Cronin emphasized that the club was still a work in progress, but baseball writers continued to file upbeat reports for their anxious readers back in New England. The general consensus in Sarasota was that this Red Sox team could win the American League pennant.

Grantland Rice, the dean of American sportswriters at the time, wrote a glowing tribute to Ted Williams in the April 11, 1946, edition of The Sporting News. Rice wrote in part, “Someone asked me to name the most interesting personality I met on the six week invasion of spring practice. I can give you his name—Ted Williams of the Red Sox, the greatest hitter in baseball today. Probably one of the greatest hitters of all time. Possibly the greatest hitter of all time.”

BARNSTORMING NORTH

The 1946 Red Sox broke camp in Sarasota in early April, heading north by train, stopping at small cities along the way to play exhibition games. “We shared a train with the Cincinnati Reds,” Johnny Pesky remembers, “and we would stop in places like Birmingham, Alabama, and Louisville, Kentucky, to play exhibition games against them.”

The stop in Louisville really stands out in Bobby Doerr’s mind. “Ted [Williams] and I went over to the Hillerich & Bradsby factory to see where they made our bats. Ted gave them all sorts of advice on how to make his bats,” Bobby laughs. “They recognized pretty quickly that he knew what he was talking about.”

The annual City Series, which was played from 1925 to 1953 between the Red Sox and their cross-town rivals the Braves, marked the end of each pre-season and the return of baseball to Boston. “It was a great rivalry,” Bobby Doerr says. “Since we played in the same city, we knew most of the Braves players, and they knew us. It was usually cold in Boston in early April,” Bobby remembers, “but we always looked forward to the games.”

The final game of the 1946 City Series was played at Fenway Park on April 14, 1946, and the crowd of 33,279, made it clear that Boston fans were ready for the return of pre-war major league baseball. And the 19-5 Red Sox victory, paced by Doerr’s 7 RBI, made it clear that the Red Sox were ready for the regular season to begin.

Red Sox fans remember spring training in 1946 as the starting point for one of the more successful clubs in team history. The 1946 Boston Red Sox went on to win 104 games—the second-best record in team history—and came within one game of capturing the World Championship. But it should also be remembered as a once-in-a-lifetime event, the year when Red Sox players returned safely from harms way.

Portions of this article appeared in various editions of Red Sox Magazine. To subscribe to Red Sox Magazine click here.

Leave A Comment